As I type these words here in my office atop the Jepson House in beautiful downtown Savannah, Hurricane Ida Lupino (or whatever it’s called) is furiously lashing my windows with wind and rain. By the time you read this it will be well on its way out into the Atlantic, but I hope wherever you are you are safe, sheltered, and unharmed.

College Football: It’s that time of year again, as the baseball season enters its last full month, to turn our thoughts to the agony/ecstasy that is college football. The season officially began last Saturday, August 26, but you probably didn’t even realize it, with few games to catch our attention. The season really begins on Thursday evening, August 31, and kicks into high gear over the Labor Day weekend. Our beloved Georgia Bulldogs are looking to be the first team to win three consecutive national championships since the University of Minnesota (!) in 1934-1936, back when Dexter was a baby. Since 1936 there have been 13 teams with a chance to win three nattys in a row, the last being Alabama in 2014, yet none have done it since the Golden Gophers during FDR’s first term. Can Georgia do it again this year? The Dawgs tee it up Saturday at 6pm against UT-Martin, and if you’re scratching your head and asking, “stepped in what?” you’re not alone. In addition to the Skyhawks, we play Ball State (Cardinals) and UAB (Blazers) as non-conference opponents. UGA’s schedule is ridiculously weak this year, with the marquee (and most difficult) matchup being Tennessee on November 18. If Georgia’s not undefeated at that point it won’t be the scheduler’s fault. Nevertheless, because we play in the SEC, ESPN still ranks the Dogs schedule as 31st in the nation out of 133 teams. We’ll make up for it next year, however, opening against Clemson at Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, and in the SEC we play at Texas, at Alabama, at Mississippi, at Florida, and home against Mississippi State, Tennessee, and Auburn. Winning a championship is incredibly difficult, so for my part there’s no expectation for a three-peat, especially with a new and untested quarterback, but with Kirby Smart, anything’s possible. Keep the crying towels handy and Go Dogs.

College Football: It’s that time of year again, as the baseball season enters its last full month, to turn our thoughts to the agony/ecstasy that is college football. The season officially began last Saturday, August 26, but you probably didn’t even realize it, with few games to catch our attention. The season really begins on Thursday evening, August 31, and kicks into high gear over the Labor Day weekend. Our beloved Georgia Bulldogs are looking to be the first team to win three consecutive national championships since the University of Minnesota (!) in 1934-1936, back when Dexter was a baby. Since 1936 there have been 13 teams with a chance to win three nattys in a row, the last being Alabama in 2014, yet none have done it since the Golden Gophers during FDR’s first term. Can Georgia do it again this year? The Dawgs tee it up Saturday at 6pm against UT-Martin, and if you’re scratching your head and asking, “stepped in what?” you’re not alone. In addition to the Skyhawks, we play Ball State (Cardinals) and UAB (Blazers) as non-conference opponents. UGA’s schedule is ridiculously weak this year, with the marquee (and most difficult) matchup being Tennessee on November 18. If Georgia’s not undefeated at that point it won’t be the scheduler’s fault. Nevertheless, because we play in the SEC, ESPN still ranks the Dogs schedule as 31st in the nation out of 133 teams. We’ll make up for it next year, however, opening against Clemson at Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, and in the SEC we play at Texas, at Alabama, at Mississippi, at Florida, and home against Mississippi State, Tennessee, and Auburn. Winning a championship is incredibly difficult, so for my part there’s no expectation for a three-peat, especially with a new and untested quarterback, but with Kirby Smart, anything’s possible. Keep the crying towels handy and Go Dogs.

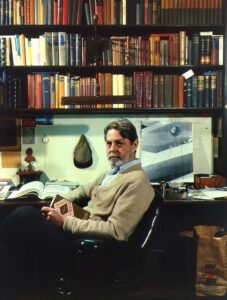

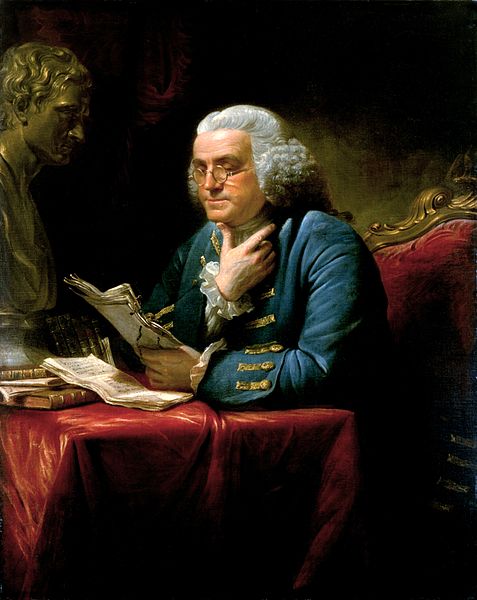

Summer Reading: I finally got around to watching Turn Every Page, the 2022 documentary about the relationship between writer Robert Caro and his editor, Robert Gottlieb. Having read Caro’s 2019 book, Working, and Gottlieb’s 2016 memoir Avid Reader, there wasn’t much new for me in the film, but it’s still great fun to listen to two craftsmen talk about what they love to do. The duo began working together more than 50 years ago on Caro’s massive 1974 bio of Robert Moses, The Power Broker. Caro is now racing the clock (he’ll be 88 in October) to finish the 5th and presumably final volume of his monumental biography of Lyndon Johnson. Caro is thorough and meticulous but not fast (it’s been 11 years since the last volume appeared), hence the title of the documentary. Gottlieb, alas, won’t get to see the finish line, having died this year on June 14 at age 92. Write, Caro, write.

Speaking of massive tomes, I recently finished the first volume of Shelby Foote’s three-volume The Civil War: A Narrative (1958), which clocked in at 810 pages of closely written text. The next two volumes are even longer, and the whole thing totals just under 3,000 pages. The work has been picked apart by Civil War scholars over the last 60+ years, but it’s still beautifully written and if you’re going to spend 5 weeks with an author, you could do a lot worse than Shelby Foote. It’s even better if you can hear his voice sounding it all out as you read.

Speaking of massive tomes, I recently finished the first volume of Shelby Foote’s three-volume The Civil War: A Narrative (1958), which clocked in at 810 pages of closely written text. The next two volumes are even longer, and the whole thing totals just under 3,000 pages. The work has been picked apart by Civil War scholars over the last 60+ years, but it’s still beautifully written and if you’re going to spend 5 weeks with an author, you could do a lot worse than Shelby Foote. It’s even better if you can hear his voice sounding it all out as you read.

Also read this summer: The first volume of Douglass Southall Freeman’s four-volume R.E. Lee (1934), a Pulitzer winner and much more critical than I’d ever imagined. I’ve never been drawn to Lee, but this biography has been sitting on my shelf since I bought it at the now-defunct Jackson Street Books in Athens 37 years ago, so I finally took the plunge. Freeman’s interpretation of Lee has long since been challenged and mostly overturned, and his insistence that Lee made the only choice he could in serving the Confederacy rather than remaining loyal to the US is hash. Still, I expected this to be full-on hagiography with Lee as saintly knight, but that isn’t the case. Freeman was far more balanced than I ever gave him credit for, but that’s what often happens when one judges without reading. As with Foote, I’ll wait a year and dig into volume 2.

I re-read James Hilton’s novel Lost Horizon (1933), about the legendary mountain-top utopia Shangri-La and the mysterious Hugh “Glory” Conway’s visit there. What an absolute joy to read. This book, like Hilton’s Goodbye, Mr. Chips, is relatively short but packs a lot into a little. Hilton is mostly forgotten now—he died of liver cancer at age 54 in 1954—but this book was one of the most popular of the 20th century. I plan to re-visit Shangri-La every summer. [Sidebar: FDR loved this book and named the presidential retreat on Maryland’s Catoctin Mountain “Shangri-La”; Eisenhower, thinking it sounded too stuffy, re-named it “Camp David.”]

Other novels read this summer: Clyde Edgerton’s Rainey (1986) (hilarious) and Ferrol Sams’s Run With the Horseman (1982) (hilarious and moving). The latter was a high-school graduation gift received 41 years ago that I didn’t read at the time but, operating under the mantra that “every book finds its day,” I’m glad I waited. The exploits of “the boy” and his relationship to his father and the rest of his small community had much more to say to me now than it would have at 17. Staying with semi-autobiographical fiction, I just started Nina Stibbe’s 2014 novel, Man at the Helm, which, so far, is, as Shelby Foote would say, “just a pleasure to be part of.”

Other novels read this summer: Clyde Edgerton’s Rainey (1986) (hilarious) and Ferrol Sams’s Run With the Horseman (1982) (hilarious and moving). The latter was a high-school graduation gift received 41 years ago that I didn’t read at the time but, operating under the mantra that “every book finds its day,” I’m glad I waited. The exploits of “the boy” and his relationship to his father and the rest of his small community had much more to say to me now than it would have at 17. Staying with semi-autobiographical fiction, I just started Nina Stibbe’s 2014 novel, Man at the Helm, which, so far, is, as Shelby Foote would say, “just a pleasure to be part of.”

Meanwhile, in preparation for an upcoming podcast, my early morning reading is Jim Cobb’s fascinating new bio, C. Vann Woodward: America’s Historian (University of North Carolina Press). Jim is B. Phinizy Spalding Professor Emeritus of history at UGA. We’ll record the podcast in September, which will be fun. Stay tuned.

At lunchtime and bedtime, I’m finishing two other books with similar themes and self-explanatory titles: Over My Dead Body: Unearthing the Hidden History of America’s Cemeteries, by Greg Melville (2022), and Sue Black’s All That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving Crimes (2018). Both are about death, dying, and what becomes of our remains when we’re gone. Perfect reading before rendering unto Morpheus the things that are Morpheus’s, as Clifton Fadiman said.

Passages: Here in Savannah and across the state of Georgia, we mourn the death this week of Frank W. “Sonny” Seiler, the legendary lawyer and owner of a succession of Damn Good Dawgs all named UGA. Sonny was serving on the Board of the Georgia Historical Society when I arrived here 25 years ago. Like everyone else, I knew him from afar as UGA’s keeper and as one of the central figures in Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (the book and the movie). Soon after I arrived in town, my boss Todd and I walked over to see Sonny in his office in the Armstrong House, across from Forsyth Park, the walls covered with oil paintings of various English bulldogs all named UGA. Introducing me, Todd explained that, like Sonny, I too was a Double Dog. Sonny cheerily waved me into his office, pointed to a chair, and said, in that inimitable voice, “Stan, siddown right heah and let the Dawgs look down upon you!” A Savannah and Georgia institution, Sonny died on Monday, August 28, at age 90.

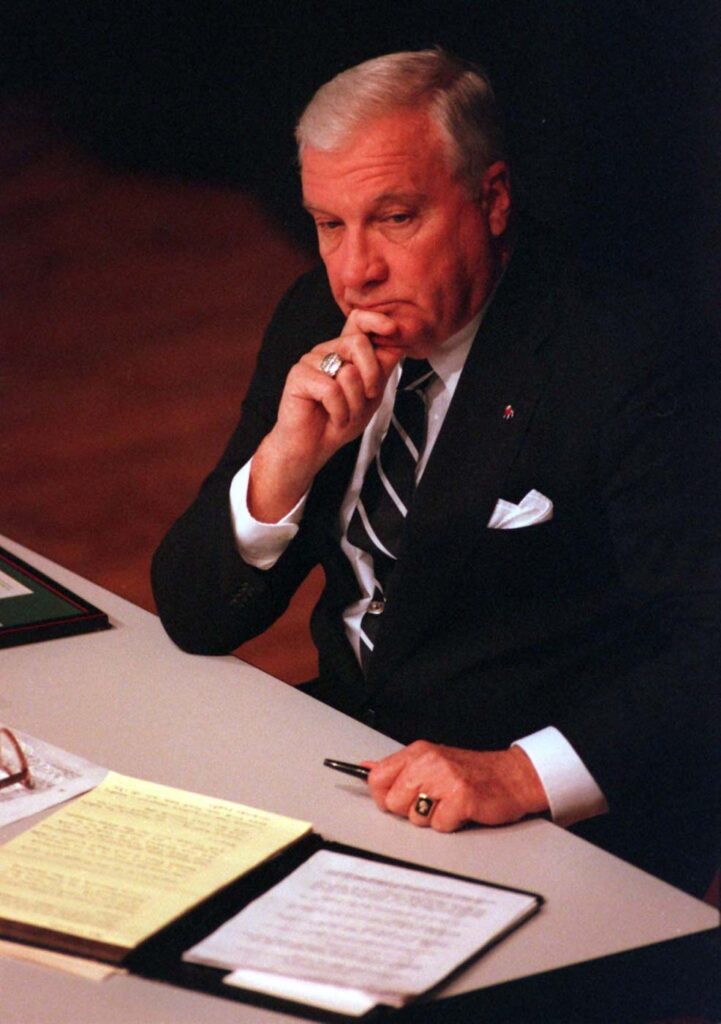

Finally, Don Smith, television producer extraordinaire, died last Friday, August 25. I had the pleasure of working with Don on “Today in Georgia History,” produced jointly by GHS and Georgia Public Broadcasting, which I wrote about in this blog. Don brought a wealth of experience to the project, having spent years at Atlanta’s WAGA, CNN, GPB, and many other places besides. The Quitman, Georgia, native was tremendously talented—winner of 22 Emmys and a prestigious Peabody—smart, wickedly funny, and equal parts sweet, grumpy, and curmudgeonly fussy. Don was the first person I knew who practiced what is now called intermittent fasting; he ate once a day. It might be lunch or dinner, but never both. Being old school, he was a gifted raconteur with a wealth of stories and jokes, almost all of them off-color. Don frequently broke up the sound stage—especially poor fellow producer Bruce Burkhardt (and me)—at all the wrong moments as we recorded on set, usually with something hilarious that began, “As the actress said to the archbishop…” Peals of laughter ensued. Don complained, groused, and fussed through it all, but once he liked you, you were golden. Though we butted heads once or twice in the beginning, fortunately Don took to me almost instantly. Every minute you spent with him was a seminar on living, and I cherished it all. Hail and farewell, dear fellow. We’ll miss you.

Finally, Don Smith, television producer extraordinaire, died last Friday, August 25. I had the pleasure of working with Don on “Today in Georgia History,” produced jointly by GHS and Georgia Public Broadcasting, which I wrote about in this blog. Don brought a wealth of experience to the project, having spent years at Atlanta’s WAGA, CNN, GPB, and many other places besides. The Quitman, Georgia, native was tremendously talented—winner of 22 Emmys and a prestigious Peabody—smart, wickedly funny, and equal parts sweet, grumpy, and curmudgeonly fussy. Don was the first person I knew who practiced what is now called intermittent fasting; he ate once a day. It might be lunch or dinner, but never both. Being old school, he was a gifted raconteur with a wealth of stories and jokes, almost all of them off-color. Don frequently broke up the sound stage—especially poor fellow producer Bruce Burkhardt (and me)—at all the wrong moments as we recorded on set, usually with something hilarious that began, “As the actress said to the archbishop…” Peals of laughter ensued. Don complained, groused, and fussed through it all, but once he liked you, you were golden. Though we butted heads once or twice in the beginning, fortunately Don took to me almost instantly. Every minute you spent with him was a seminar on living, and I cherished it all. Hail and farewell, dear fellow. We’ll miss you.

Stay safe, and until next time, thank you for reading.

The Philadelphia Phillies are National League champions? The same team that finished in third place in the National League East?

The Philadelphia Phillies are National League champions? The same team that finished in third place in the National League East? Hurricane Ian has moved through Florida and is headed northeast, expected to make landfall sometime on Friday afternoon, September 30, just east of here in South Carolina, exact destination unknown. For a while it looked like it was headed straight for us here in Savannah, and with a wobble here or there, it may still. Outside my window the skies are dark, and the trees are already bent low with the winds, which, coming from the north, have also refreshingly brought fall here as well.

Hurricane Ian has moved through Florida and is headed northeast, expected to make landfall sometime on Friday afternoon, September 30, just east of here in South Carolina, exact destination unknown. For a while it looked like it was headed straight for us here in Savannah, and with a wobble here or there, it may still. Outside my window the skies are dark, and the trees are already bent low with the winds, which, coming from the north, have also refreshingly brought fall here as well.