This Dispatch comes to you from the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Georgia. Join Dr. Deaton as he discusses the history of the Appalachian Mountains, Vogel State Park, the Chattahoochee National Forest, and the natural wonders North Georgia has to offer.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

The Contradiction of a Free Nation Built By Forced Labor

The Georgia Historical Society is launching a new and exciting initiative soon, and in preparation for it I’ve been reading deeply in the literature of race in American history.

I’ve been reading about this topic for almost 40 years, but my current course of reading in this subject actually began a couple of years ago, when I embarked on a project to actually read many of the books that I had been assigned in graduate school—big, important works that I was supposed to read but didn’t, at least not as closely as I would have liked. Books like E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class, Lawrence Goodwyn’s Democratic Promise, David Montgomery’s The Fall of the House of Labor, and Keith Thomas’s Religion and the Decline of Magic, to cite just a few. These were all important, magisterial works that deserved to be read in full.

They’re also very big books, most of them clocking in at well over 600 pages, which explains why I didn’t read them as closely as I should have at that time. For the uninitiated, it was not uncommon in grad school to be assigned two books of that size every week—along with several lengthy articles—in each and every class. Speaking strictly for myself—but as every history grad student surely knows—there was simply no way to read every word of every book, to read all those articles, and also keep up with all the writing tasks and the grading or teaching assignments one might also have. Learning to read by skimming but still discerning the argument in every book is the first art of history graduate school.

All of which explains why for the better part of the 1990s my diet was terrible, I rarely saw the inside of a gym, and my cultural knowledge of TV shows and movies from that era is practically non-existent. I was simply trying to keep my head above the proverbial floodwater of pages.

Two years ago this week, when historian David Brion Davis died on April 14, 2019, at the age of 92, I read his obituary and realized that his monumental book, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture, was one of those books I had unjustly skimmed all those years ago. I resolved then and there to rectify that.

Davis was a towering scholar of slavery in the Americas, a long-time professor at Yale, and the founding director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition. Ira Berlin, himself an award-winning historian of slavery, said of Davis: “No scholar has played a larger role in expanding contemporary understanding of how slavery shaped the history of the United States, the Americas, and the world than David Brion Davis.”

In 1998, at my first academic conference as a newly minted Ph.D., I read a paper on slavery in Charleston during the American Revolution, based on my dissertation research. The first person who came up from the audience afterward to commend my work was an older gentleman who was humble, modest, and gracious. I thanked him, looked down at his nametag, saw “David Brion Davis,” and was rendered speechless. The man who was arguably one of the most important historians in America took the time to offer kind words and encouragement to an eager but green-as-a-granny-smith-apple rookie who had done nothing important at all. It was a lesson and a moment I never forgot.

As his obit pointed out, Davis began his career in post-war America when “most historians espoused the ‘moonlight and magnolias’ myth, in which slavery was viewed as a paternalistic, mutually beneficial relationship between slaves and overseers. The Civil War was largely unrelated to slavery, most scholars said at the time, and the system was inefficient and marginal and would have ended on its own without a war.”

Davis was one of the pioneering scholars who stormed the ramparts and helped to dismantle that view. “Slavery, he demonstrated, was an economic engine no less productive or efficient than a 20th-century Detroit factory line. It was also a horror to enslaved Africans and marked a vexing paradox in American life.”

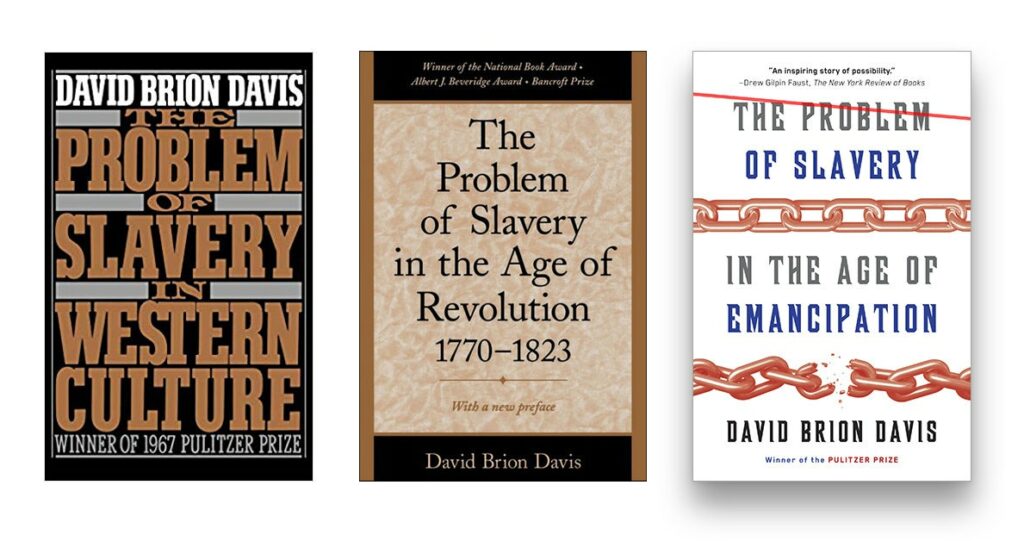

Davis’s scholarly monument is his “Problem of Slavery” trilogy. The series included the aforementioned The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (1966), which won the 1967 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction (beating out Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood); The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (1975), which received a National Book Award and the Bancroft Prize for American history; and The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Emancipation (2014), which won a National Book Critics Circle Award.

Eric Foner called the trilogy “one of the towering achievements of historical scholarship in the past half-century.” “No one,” Foner said, “did more to inspire the revolution in historical understanding that places slavery at the center of American history and indeed the history of the West.”

In addition to his trilogy, Davis published Slavery and Human Progress (1984) and Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (2006), which Ira Berlin in the New York Times called a “tour de force of synthetic scholarship.” In that book, Davis wrote, “We must face the ultimate contradiction that our free and democratic society was made possible by massive slave labor.”

President Barack Obama awarded Davis the National Humanities Medal in 2014 and hailed him as a scholar whose lifetime of achievement “has shed light on the contradiction of a free nation built by forced labor, and his examinations of slavery and abolitionism drive us to keep making moral progress in our time.”

So it was that in the late summer of 2019, more than 25 years after I had first been assigned the book in a graduate seminar, I sat down to read—patiently and with great attention—Davis’s Pulitzer-Prize winning book, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture.

Davis was interested in the development of anti-slavery thought in the 18th and 19th centuries: when and why did slavery become a moral problem, when it had existed since antiquity without anyone raising objections to it? As Davis phrased it, “Why was it that at a certain moment of history a small number of men not only saw the full horror of a social evil to which mankind had been blind for centuries, but felt impelled to attack it?”

In this and in subsequent volumes, Davis traces ideas about slavery from its Judeo-Christian origins through emancipation, and unequivocally places the institution squarely at the center of the New World, and the creation of the American Republic.

Indeed, Davis called slavery “the central fact of American history,” an assertion deeply troubling to many Americans who would rather celebrate the past than confront the enormity of the history and legacy of bondage.

Davis’s work is more important and timely than ever. Many people in this country frequently ask why we still talk about slavery. Can’t we just move on? Slavery’s been over for more than 150 years, they say, what good can possibly come from our constantly bringing it up? And what of those historians and teachers, they ask, who insist on placing it at the heart of the American experience? Surely, they insist, they’re wrong to do that. Aren’t they over-stating the importance of an institution that only momentarily cast a dark shadow over the American past? Shouldn’t we be celebrating the American story instead of focusing on something so negative?

David Brion Davis answered this question head on: Man is the only animal, he said, that has the “ability to transcend an illusory sense of now, of an eternal present, and to strive for an understanding of the forces and events that made us what we are.” As those who opposed slavery in previous centuries demonstrated, people “are not compelled to accept the world into which they are born.”

For Davis, a greater and deeper understanding of slavery and its legacy should bring not despair but hope: “A frank and honest effort . . . to face up to the darkest side of our past, to understand the ways in which social evils evolve, should in no way lead to cynicism and despair or to a repudiation of our heritage. The more we recognize the limitations and failings of human beings, the more remarkable and even encouraging history can be.”

As the United States approaches its 250th anniversary as an independent and mature nation, we have reached another important crossroads in our national development. America is once again grappling very publicly with difficult and tangled questions of racial injustice. Will anything really be different this time?

A historian who spent his entire professional career peering into the darkness saw light ahead: “The development of maturity means a capacity to deal with truth.” We can only hope that he was right.

National Poetry Month: Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening

Have you ever memorized a poem just because you loved it? To commemorate National Poetry Month, Dr. Deaton in this Dispatch considers the power of poetry to evoke the beauty and tragedy of life as no other literary style can–and recites his personal favorite.

Dred Scott: The Worst Supreme Court Decision Ever?

In this Dispatch, Dr. Deaton discusses the case of an enslaved man, Dred Scott, whose pursuit of freedom went all the way to the Supreme Court–and helped cause the Civil War.

Climbing Mount Nevins

Fifty years ago this week, on March 5, 1971, historian Allan Nevins died in Menlo Park, California, at the age of 80. Nevins was one of the most influential and prolific historians ever, the author of so many books, articles, essays, and reviews, that no one really knows exactly how prolific he was. He is best remembered now as the author of the 8-volume work known collectively as Ordeal of the Union, a history of the United States from 1847 through 1865, covering the period from the end of the Mexican War through Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

I confess to being fascinated by Allan Nevins since I first came across a short tribute to him written by another historian, Ray Allan Billington, as a preface to a volume of Nevins’ essays published after his death, Allan Nevins on History. If history ever had an honest-to-goodness ambassador, an enthusiast par excellence, Nevins was it. He lived and breathed the subject as perhaps no one else ever did, and his enthusiasm captured my young imagination—and still does all these years later. He was a fierce advocate for good, readable history, written for that elusive Every Man and Every Woman, not for the specialist or the academic. He always was, in the best sense of the word, a public historian. Above all, he loved and collected books, a man after my own heart.

It was that love of books that first interested my younger self in Allan Nevins, just starting to get seriously interested in history and building my own library. At dear old Oxford Too, that cavernous and now-defunct used-bookstore in Atlanta, I came across a copy of Nevins’ classic The Gateway to History (1962). The essays within were historiographical and bibliographical gems (even though I didn’t know what those words meant then) with titles like “A Proud Word for History,” “Literary Aspects of History,” and “The Reading of History.” Every page dripped with Nevins’ passion for readable, clear history and his wide and deep knowledge of authors and books. I was hooked; I still have that book and have read it to tatters.

As a third-year student at the University of Georgia, I joined the History Book Club and as a gift for joining received all 8 volumes of Nevins’ Ordeal of the Union, published between 1947 and 1971. I put them on my shelves and there they remained for years, set aside for that day when I’d have more leisure time, when the required reading of graduate school and then professional obligations were past. Finally, just last year during the pandemic, 35 years later, I pulled down the first volume and am currently finishing the second.

The work is divided into three different series: Ordeal of the Union, covering 1847-1856 (2 volumes); The Emergence of Lincoln, 1857-1861 (2 volumes), and The War for the Union, 1861-1865 (4 volumes). As Gary Gallagher has noted, they are outstanding works of scholarship and literature, covering a vast canvas of American political, economic, diplomatic, social, and military history. The sweep is enormous, the research voluminous, the writing clear and penetrating. The first two volumes won the prestigious Bancroft Prize and the last two earned Nevins posthumously the National Book Award. If Nevins had done nothing else, these 8 volumes would be a monumental literary legacy of enduring fame.

But these volumes hardly scratch the surface of Mount Nevins. Indeed, to give his bare-bones biography hardly does him justice. He was born in Camp Point, Illinois, in 1890 to a hard-working Scots Presbyterian farmer and his Irish wife. Nevins later joked that he never really worked hard a day in his life after he left that farm. His father had a library of 500 volumes on which Nevins cut his intellectual, and from that point forward he became an indefatigable reader and collector of books.

Nevins graduated with Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from the University of Illinois, and that was the end of his formal education. He never received the union card of the professional historian, the Ph.D., in part, it was later said, because nobody knew enough to question him during the oral examinations. He published his first book at age 24 and never stopped writing and publishing, despite working day jobs for several New York newspapers and then teaching full-time at Cornell University and then Columbia.

As best as anyone can figure, Nevins wrote upwards of 50 books, edited about 100 more, and perhaps penned a thousand articles and essays over a career that spanned 57 years. He won the Pulitzer Prize twice. Even more impressive, he won them for biographies of two historical figures that you’d avoid unless you lost a bet: Grover Cleveland, the 22nd and 24th president, and Hamilton Fish, governor of New York, US Senator, and Grant’s Secretary of State. He also wrote major biographies of John C. Fremont, John D. Rockefeller (2 volumes), Henry Ford (3 volumes), Henry White, Abram Hewitt, and Herbert Lehman. Dip into any of them and you’ll find that, as in all of his books, the research is meticulous and exhaustive, the writing flawless.

Besides biographies, Nevins wrote a history of the New York Evening Post, of the American States During and After the American Revolution, of The Emergence of Modern America, a volume on American Press Opinions from Washington to Coolidge, a history of political cartoons, an edited collection of several volumes of editorials by journalist Walter Lippman, two volumes on American foreign policy, other smaller volumes too numerous to count, as well as the aforementioned 8 volumes of the Ordeal of the Union. I won’t even begin to list all the other works he edited.

In addition to teaching full-time and writing all those books, Nevins oversaw about 100 doctoral dissertations at Columbia, wrote a never-ending stream of book reviews, articles, and essays for publications far and wide, contributed dozens of entries to the Dictionary of American Biography, founded the first Oral History program in the nation at Columbia in 1948, amassed manuscript collections for the Columbia library, all while keeping up a prodigious correspondence of more than 12,000 letters during his lifetime.

As they say in the late-night commercials, but wait, there’s more: During World War II he served as special representative of the Office of War Information in Australia and New Zealand in 1943-1944, and in 1945-1946 worked in London as chief public affairs officer at the American embassy. He also served two stints as Harmsworth Professor of American History at Oxford University, as well as terms as president of the American Historical Association, the Society of American Historians, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He also was instrumental in founding American Heritage magazine, to reach an even larger audience of general readers interested in history.

And that’s not all: for 19 years, from 1938 to 1957, Nevins hosted a 15-minute radio show called “Adventures in Science,” which covered a wide variety of medical and scientific topics. When television arrived, he took to that medium as well. He served on government commissions, wrote speeches for presidents, and continued to write for national publications, always reaching a wide audience far beyond the academy. He had a lifelong disdain for those whom he called “pedants,” exemplified in his mythical “Professor Dryasdust” who was concerned only with talking to other academics in unreadable jargon.

After he officially “retired” from Columbia in 1958, Nevins became a senior researcher at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, wrote an introduction for John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage, chaired the national Civil War Centennial Commission from 1961-1966, edited the 15-volume Civil War Impact series, and continued to publish, even after a crippling stroke meant re-learning how to type. He worked nearly to the end and published the last volumes of Ordeal of the Union in the year of his death.

His love of history went beyond his own teaching and writing, however: In 1965, Nevins gave Columbia University $500,000 to endow a chair in economic history, though he never made more in salary than $11,500 annually. His Scots’ upbringing had served him well—he pinched pennies and invested book royalties wisely.

When did he eat and sleep, and where did he get that energy? Missing from the articles written by and about him is anything about his routine and his work habits, how he managed to squeeze out so much productivity in a 24-hour day, for so many years on end. No less than publisher Alfred A. Knopf described Nevins as “the most industrious and hardworking man of my acquaintance.”

Though he worked 12-hour days routinely, by all accounts he was a good and attentive father to his two daughters (whom he affectionately called “Pudge” and “Cub”), even if he did take his wife to Civil War battlefields on their honeymoon. Douglas Southall Freeman’s Spartan schedule—getting up at 2:30 in the morning, writing for hours in his attic study before going to work, rigorously curtailing his social engagements—was lionized even in his own lifetime, but Nevins’ remains a mystery. Still, stories and anecdotes about him are legion.

This from Billington’s essay, “Allan Nevins, Historian, A Personal Reminiscence”: “Life to him was a continuous race against time, with every second so precious that it must be used for productive purposes. Those who knew him during his years at Columbia recall his frantic dash to or from the subway each day, his arms laden with books and a portable typewriter, his short legs chopping the ground, a graduate student panting at his side seeking word on a freshly finished chapter of a doctoral dissertation. At the Huntington Library, after he had reached an age that slows most men, Allan slackened not one whit. His entrance each morning was a spectacular event; he came laden with a briefcase bulging with work done the night before, his arms heavy with books and manuscripts. The elevator to the second floor was too slow; his steps pounded up the stairs at breakneck speed; he sprinted down the hall to his office.” Time was so precious to him that he was overheard telling his secretary one morning, “I got up this morning thinking it was Thursday. Mary [his wife] told me it was only Wednesday. I’ve gained a whole day.”

Clocks at the Huntington were kept five minutes fast in order to get Nevins out of the building each day before it closed.

To no one’s surprise, he was notoriously absent-minded: Witnesses said he forgot his own son-in-law’s name; he once arrived at work wearing two neckties, one on top of the other; and lunch guests were kept waiting so long while he finished one more sentence that it was not unusual for them to give up and eat without him. He once gave a tour of his home to two visiting young ladies, reached the door of his study, announced, “this is where I work,” sat down at his typewriter and forgot his guests entirely. After an awkward few minutes, they found their way out and left. Cocktail parties at the Nevins home were always presided over by Mary Nevins, until Allan came bounding down the steps, frantically putting on his jacket and breathlessly welcoming his guests.

It wasn’t unusual after dinner for him to offer tours to those who wanted “to see my books,” as he led visitors around his book-crammed rooms, including the bathroom, where he opened a medicine cabinet with two of three shelves lined with books. “I want to show you an example of Mrs. Nevins’ tyranny,” he complained, pointing, “She will not give me that shelf.” He had books everywhere—a vast collection in his office at Columbia, several thousand in a farmhouse in Connecticut, and stacked floor to ceiling in his 3-car garage after he moved to California. He once feared that the 15,000 in his New York home would cause the second floor to collapse. Like a true bibliophile, Nevins kept buying books and remained a voracious reader to the end.

The end came 50 years ago this week in a nursing home in Menlo Park, California. After a crippling coronary and a paralytic stroke, Allan Nevins died at age 80 on Friday, March 5, 1971. His obituary was carried on the front page of the New York Times, a rare tribute for a writer of history. Bruce Catton, no slouch writer himself, called Nevins “one of the very greatest historians we have ever had.” He was buried at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York.

Arnold Bennett wrote that all authors, whether of history, poetry, fiction, or biography, all have one thing in common: they are all trying to capture something beautiful and emotional in their writing. Death finally ended Allan Nevins’ insatiable curiosity about every aspect of the American past, but his unquenchable desire, his passion to make history understandable, readable, and ultimately relevant and useful to all the rest of us is still there for those who care to discover it. Nevins has been gone for a half century, but Mount Nevins remains.

There is a story that President Kennedy hosted a meeting in the White House that included Nevins. When the meeting ended, Kennedy put his hands on Nevins’ head and said, “God, I wish I had that brain.”