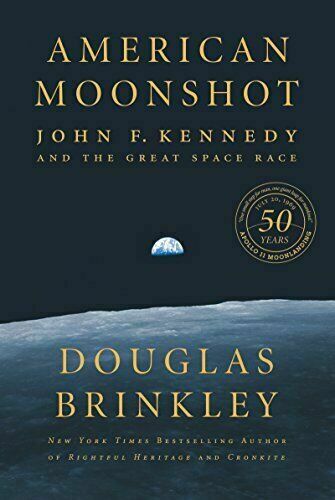

Douglas Brinkley, American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race (Harper Collins, 2019, 548 pp.)

Since humans first crawled out of the primordial soup millions of years ago, they have gazed up at the moon in the night sky and dreamed of what it was like. Only 24 people–all men–have ever been there. Twelve of them walked on it.

With the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing this summer, I thought I’d check out Douglas Brinkley’s new book on that historic event. Your favorite blogger reviewed Brinkley’s biography of Walter Cronkite a few years ago [Cronkite was a space junkie], and this new book seemed a natural with all the fuss over the moonshot anniversary.

Despite the title, American Moonshot is not a history of the space program or of Apollo 11, but is instead a history of JFK’s leadership of the program up until his death. It is very thorough through the Mercury program, less so for Gemini or Apollo.

Still, the book is a goldmine of information and insights, as you’ll see below. And Brinkley makes clear that without JFK’s single-minded devotion to space exploration, the great events of July 1969 would never have happened.

As I watched the commemorations of Apollo 11 this summer, I was deeply moved once again by the tremendous courage of the astronauts, from Mercury to Gemini to Apollo. They willingly placed themselves on top of rockets that could have blown them to bits; they could have been sent into orbit and never returned, or they could have been stranded on the moon to die very lonely deaths. Their country called them and they answered, in the name of science, exploration, duty, and Cold War patriotism.

Still, the thing that I can’t help wondering about the moon landing of 1969 is the dramatic impact it had on everyone at the time–President Nixon called it “the greatest week in the history of the world since creation”–and how little of that effect seems to have lingered across the years. The space shuttle program gave NASA a boost in the 1980s (at least until the Challenger disaster) but when’s the last time you talked to someone who dreamed of being an astronaut when they grow up?

Has anything ever seemed so momentous at the time that has arguably had so little impact on the world now? Was all the sacrifice and billions spent to get there ultimately worth it?

I think it was, but a lot people then and now disagree, perhaps most famously Gil Scott Heron in his 1970 song, “Whitey on the Moon”:

“I can’t pay no doctor bill.

(but Whitey’s on the moon)

Ten years from now I’ll be payin’ still.

(while Whitey’s on the moon)

The man jus’ upped my rent las’ night.

(’cause Whitey’s on the moon)

No hot water, no toilets, no lights.

(but Whitey’s on the moon)”

To be sure, as Walter Isaacson pointed out, while working to solve the problems of manned spaceflight, NASA laid the foundations for all kinds of modern technology, to wit: satellite TV, GPS systems, microchips, virtual reality technology, solar panels, carbon monoxide detectors, cordless power tools, bar coding, even the Dustbuster.

Research into space medicine contributed to radiation therapy for treating cancer, foldable walkers, personal alert systems, CAT and MRI scans, muscle stimulant devices, advanced types of kidney dialysis machines, and many others.

What NASA didn’t invent: Teflon (developed by DuPont in 1941), Velcro (invented in 1941 by a Swiss engineer to remove burrs stuck in his dog’s fur), or Tang (1957).

Rather than reviewing Brinkley’s book in detail, I thought it might be fun to provide you with a bulleted list of some of the things I learned that I didn’t know before. What follows is another list in the ever-popular feature known as

Fun Facts Known by Few

- Jules Verne, writing in the 1860s, predicted that the United States would beat Russia to the moon, that the voyage would be launched from Florida, and that it would take four days–all of which turned out to be true.

- Theodore Roosevelt (no longer in office) was the first president to fly in a plane, October 11, 1910. The first sitting president to fly was FDR, January 14, 1943.

- In a 1920 headline, the New York Times famously lampooned Robert Goddard’s idea of a rocket being able to operate in a space vacuum. After Apollo 11 landed on the moon 49 years later, the Times famously issued a public retraction.

- Brinkley pulls no punches on former Nazi rocket scientist Wernher von Braun: “NASA was lucky to have a rocket engineer as talented as von Braun to work on Apollo. But he shouldn’t be remembered as an American hero. His direct role in the Nazi concentration camp labor programs, where thousands perished under inhumane conditions, makes him a pariah figure of sorts”

- Following his success with the Nazi V-2, von Braun worked to design the first trans-Atlantic ballistic missile, which Hitler wanted to use to attack New York, Washington, and Boston. It was called “Projekt Amerika.”

- A Nazi V-2 rocket launched on October 3, 1942, broke the sound barrier and traveled to an altitude of 52 miles, reaching the ionosphere and marking the first time in history that a man-made object had technically ever flown beyond Earth’s atmosphere. On June 22, 1944, another V-2 became the first man-made object to reach outer space.

- Hitler’s commitment to the V-2 rocket meant that Nazi rocket engineers would work on and solve many of the problems of space flight that ultimately helped to speed up the moon landing by decades.

- JFK enrolled at Embry-Riddle Seaplane Base in Miami in 1944 to learn to fly; his flight log confirming this was not discovered until 2018.

- In 1946, the Army Signal Corps bounced radio waves off the moon and received the reflected signals back, proving that radio transmissions through space and back to Earth were possible. This would be crucial for space exploration.

- On September 14, 1961, the Soviets unmanned Luna-2 spacecraft crash-landed on the moon, becoming the first man-made device to touch another planetary body.

- When the first Atlas rocket that would launch the Mercury astronauts into space exploded just after liftoff during its first test, astronaut Alan Shepard quipped, “Well, I’m glad they got that out of the way.”

- In 1961, as planning for Apollo began, NASA identified more than 10,000 separate tasks that had to be accomplished to put a man on the moon.

- Alan Shepard was the first American in space aboard Freedom 7 in 1961 and is the oldest man to have walked on the moon, as commander of Apollo 14 in 1971. He was 47.

- A reporter asked Shepard what his thoughts were as he sat waiting on the launch pad aboard Freedom 7. His reply: “The fact that every part of this ship was built by the lowest bidder.”

- In 1999, the Liberty Bell 7 was discovered and recovered from the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, 16,000 feet below the surface, almost 38 years to the day after Gus Grissom splash landed on July 21, 1961.

- The Soviet cosmonaut Gherman Titov, who piloted the Vostok 2 at age 25 in August 1961, was the youngest person ever to fly in space. He died in 2000, age 65.

- In April 1962, JFK had a 79% approval rating as president. Only 12% disapproved of his performance.

- JFK’s favorite beer was Heineken

- Cape Canaveral flight director Chris Kraft thought astronaut Scott Carpenter performed horribly aboard Aurora 7 in May 1962, talking to himself, peering out the porthole, and ignoring NASA requests to check his instruments: “I swore an oath that Scott Carpenter would never fly again.” He didn’t. Kraft died July 22, 2019, age 95, two days after the 50th anniversary of the moon landing.

- Dr. William Lovelace II, an aeromedicine pioneer who chaired the Special Advisory Committee on Life Science, believed that women were physiologically better equipped for space travel than men. In 1959 he invited American aviator Geraldyn “Jerrie” Cobb to take the same tests as the Mercury astronauts, along with 18 other female aviators. They graduated with flying colors and the those at the top became known as the “Mercury 13,” ranging in age from 23 to 41. When NASA got wind of it, they shut the entire program down: “Since there is no shortage of qualified male candidates, there is no need to train women for space flight.” John Glenn came out publicly against the program as well. The next year, the Soviets did what the Americans wouldn’t, making Valentina Tereshkova the first woman in space, in June 1963. She orbited the Earth 48 times and remains the only woman to have been on a solo space mission. It would take the Americans 20 more years to send Sally Ride into space aboard the Challenger in 1983.

- During NASA’s heyday between 1964 and 1969, the space agency employed 36,000 people, hired 400,000 contractors, and operated facilities worth $3.65 billion.

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower always derided the frantic moon-shot efforts as an unnecessary and expensive Cold-War stunt. He died on March 28, 1969, nearly 4 months before Armstrong and Aldrin landed on the moon.

- Jackie Kennedy sent Wernher von Braun a note two months after JFK’s death, lamenting that her late husband was “at least given time to do some great work on this earth, which now seems such a miserable and lonely place without him.”

- As the Apollo 11 launch approached, former LBJ Press Secretary Bill Moyers and future Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan lobbied the Nixon administration to name the spacecraft the John F. Kennedy. Nixon refused and did not mention JFK in the days before or after the moon landing.

- 528 million people around the world watched the moon landing on television.

- Neil Armstrong took a fragment of the Wright brothers’ famous Kitty Hawk plane with him on Apollo 11, linking man’s first successful flight with the first moon landing.

- A total of 12 men have walked on the moon, all between July 1969 and December 1972. Four of them are still alive: Buzz Aldrin, Harrison Schmidt, Charles Duke, and David Scott. NASA has pledged to put a woman on the moon as part of Artemis by 2024.

Finally, perhaps my favorite story of all: just before climbing back into the Eagle and leaving the moon for the last time, Neil Armstrong reminded Buzz Aldrin to leave behind some NASA-sanctioned mementos he had brought with him. Aldrin reached into his shoulder packet and pulled out a package containing four items: two medals honoring Soviet cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin–the first human to orbit the Earth–and Vladimir Komarov, both of whom were killed in separate 1967 accidents; an Apollo 1 patch that memorialized Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee, all killed in the Apollo 1 fire in 1967.

These were fitting tributes and recognition, deep in the midst of the Cold War, of the courage and sacrifice of their American and Soviet colleagues, upon whose shoulders they stood.

The last item was an olive-branch pin, symbolizing that the Apollo 11 astronauts had “come in peace for all mankind.”

Aldrin bent down and laid the package on the lunar surface. It’s still there.

The next time you look up at the moon, think of that small bag, and reflect a moment on all that it symbolizes, and on the giant leap it took to place it there.