“Aprils have never meant much to me,” says Truman Capote in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and I agree with him. I was made for autumn. Give me, as Ray Bradbury wrote, “That country where it is always turning late in the year. That country where the hills are fog and the rivers are mist; where noons go quickly, dusks and twilights linger, and midnights stay.”

“Aprils have never meant much to me,” says Truman Capote in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and I agree with him. I was made for autumn. Give me, as Ray Bradbury wrote, “That country where it is always turning late in the year. That country where the hills are fog and the rivers are mist; where noons go quickly, dusks and twilights linger, and midnights stay.”

If you’ve been paying any attention at all—and you have—then you know I love this season more than any other. November particularly, but December too, and yes, December is fall in Savannah—and technically everywhere else till winter officially arrives on December 21. But December truly is autumn here, and as I’ve said elsewhere, it’s the best month of the year to be in this lovely little burg.

Why? Just take a casual walk in any direction and you’ll see and feel it. The students are on winter break, and tourists are few. Parking is plentiful. There’s no waiting in restaurants and bars. Temperatures are in the 50s, there are no sand gnats or mosquitoes, the sun is low on the horizon, the leaves are changing, and the deafening roar of summer’s cicadas is gone for another season. The quiet you hear walking through the squares is almost startling. The city’s beauty is on full display in the lengthening shadows of the slanting afternoon sun. The sultriness of summer is gone, the St. Patrick’s Day mob and the gawking tourists of spring are still three months away, and for now nirvana reigns supreme. Draw near the fire on a cool and dark December twilight in your favorite downtown pub and have a glass of cheer. In December Savannah really is Charm City.

still three months away, and for now nirvana reigns supreme. Draw near the fire on a cool and dark December twilight in your favorite downtown pub and have a glass of cheer. In December Savannah really is Charm City.

The return of December means several other more unpleasant things, however, besides the fact that you’re behind on your holiday shopping. For UGA fans it means settling for another 9-3 season that should have been much better, while wrapping yourself in what has become an annual December ritual: telling yourself it’s okay because “Mark Richt is such a classy and nice guy.” Unlike that Jackass in Columbia or that Stiff Guy in Tuscaloosa Who We Wish We Had or that Other Jackass That Wears a Visor at Auburn. Who cares if we’re playing in a Bowl Named for a Department Store rather than a playoff game. We’ve got the Last Nice Guy in Sports coaching our team, by golly, and we’re gonna keep him. Okay, Stan, move on, enough of that.

What else? For Falcons fans December means bracing for yet another disappointing season while being pleasantly surprised that a 5-8 record gets you tied for first place in the NFC South. Might there be January football in Atlanta after all? Perchance to dream.

December might bring the melancholy end of college football season but this year it also brings the anticipation of the first-ever four-team playoff. Then you realize that it’s yet another glorious way for the NCAA to avoid choosing a real and undeniable college football champion the way it does in basketball and every other sport—except for the most popular one in America.

But thank goodness December also brings wood-burning fires, Christmas tree smells, Old Fezziwig Ale, Holiday Porter, bourbon eggnog and pumpkin spice coffee creamer. It is indeed a downright glorious time to be alive. It’s also time to take stock of our autumn reading while planning what lies ahead to read during the long nights of winter. Here’s what I’ve been reading this fall, broadly defined as Labor Day to Thanksgiving:

Philosophy and History: Did he really say “philosophy”? Indeed I did. Long-suffering followers may recall that in the summer I was reading Nature’s God: The Heretical Origins of the American Republic by Matthew Stewart (Norton, 2014). If Jefferson and Hamilton are the pole stars of the continuing political differences in this country—how big should government be and what should it do?—then the other eternal conflict and tension has been between the Enlightenment and the Reformation—reason vs. religion.

The titanic struggle between rational thought (philosophically defined) and emotionally charged revealed religion is still alive and well in American culture, politics, and society. Recent polls continue to show that Americans would give fewer votes to an avowed atheist than to another fictitious politician of almost any religious stripe, including presumably Muslim. Some states still have religious tests on the law books expressly forbidding atheists from holding office. Was the United States in fact founded by infidels, free thinkers, skeptics and outright atheists, as Stewart asserts, and if so, doesn’t that give the lie to this being a “Christian nation”? He makes a convincing argument but as I’m fascinated by this subject, I wanted to dig a little deeper. I read two other books, one a classic and the other new, to provide a little more context.

The Enlightenment can be defined as a belief system built upon the premise that we understand nature and man best through the use of our natural faculties—as opposed to a belief in the supernatural and revealed religion. It’s another way of exploring the age-old questions, What is the nature of the universe and man’s place in it?

The Enlightenment can be defined as a belief system built upon the premise that we understand nature and man best through the use of our natural faculties—as opposed to a belief in the supernatural and revealed religion. It’s another way of exploring the age-old questions, What is the nature of the universe and man’s place in it?

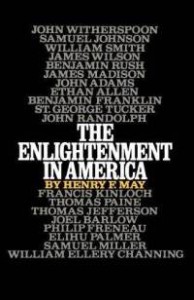

Henry F. May’s The Enlightenment in America was first published in 1976 (Oxford University Press), and his conclusions, as you might expect, are much less bold than Stewart’s even as he is more careful with the evidence. He divides the Enlightenment in America into four overlapping periods:

- The Moderate Enlightenment, 1688-1787, characterized by the defense of balance and order in all things, a belief, May asserts, that is still deeply imbedded in American institutions (or at least it was in 1976).

- The Skeptical Enlightenment, 1750-1789, the Enlightenment of Voltaire and David Hume, characterized by skepticism about religious dogma, which May writes was the least influential in America.

- The Revolutionary Enlightenment, 1776-1800, the Enlightenment of Jefferson, Paine, and the French Revolution, the belief in the clean sweep and the new start, characterized by the optimism that men would be more free and morally better in the future. Jefferson firmly believed that all Americans would eventually be Unitarians. Instead Unitarianism became the religion of the upper class of eastern Massachusetts.

- The Didactic Enlightenment, 1800-1815, relying heavily on the Scottish Enlightenment, with a firm belief in moral values, the certainty of progress, and the importance of culture, particularly literature.

None survived far into the nineteenth century intact, and all ran headlong into the anti-intellectualism and religious enthusiasm of the Second Great Awakening and advent of Jacksonian Democracy. In the end, if our Founders were indeed freethinkers, as Matthew Stewart contends—and undoubtedly many if not most of them were—then there is a curious disconnect between our own intellectual heritage and the world we’ve somehow created. Understanding it and explaining it will continue to provide fertile ground for philosophers and scholars for years to come.

The Pursuits of Philosophy: An Introduction to the Life and Thought of David Hume by Annette C. Baier (Harvard University Press, 2011) is a more recent analysis of one of the most controversial thinkers of the 18th century. The man lauded and damned as an infidel and outright atheist in his own time was at heart really just an agnostic who subscribed to the “live and let live” theory. Hume didn’t know if God existed; He might, and He might not. Hume understood the human need to believe in an all-knowing, all-powerful supernatural being who controlled and supervised everything we do. But he argued that no one could prove that deity’s existence definitively one way or the other, and therefore no one should ever force that belief on other people, particularly using the power of government or laws. And unlike most people, Hume was content with not knowing. Even downright happy. He didn’t try to change his Christian friends’ minds, and he asked them not to try to change his. As Baier writes, “He valued his friendships more than he cared about his friends’ agreement with his views.” Good advice for all of us in this age of Facebook rants.

The Pursuits of Philosophy: An Introduction to the Life and Thought of David Hume by Annette C. Baier (Harvard University Press, 2011) is a more recent analysis of one of the most controversial thinkers of the 18th century. The man lauded and damned as an infidel and outright atheist in his own time was at heart really just an agnostic who subscribed to the “live and let live” theory. Hume didn’t know if God existed; He might, and He might not. Hume understood the human need to believe in an all-knowing, all-powerful supernatural being who controlled and supervised everything we do. But he argued that no one could prove that deity’s existence definitively one way or the other, and therefore no one should ever force that belief on other people, particularly using the power of government or laws. And unlike most people, Hume was content with not knowing. Even downright happy. He didn’t try to change his Christian friends’ minds, and he asked them not to try to change his. As Baier writes, “He valued his friendships more than he cared about his friends’ agreement with his views.” Good advice for all of us in this age of Facebook rants.

Hume also rejected the notion of original sin, repulsed by the idea that men should be ashamed of what were natural human impulses, such as sexual desires. From that day to this Hume’s ideas have been denounced as heretical, revolutionary and downright dangerous. Samuel Johnson detested Hume, and that fact alone makes him worthy of our respect and attention (for more on Johnson, keep reading). It’s worth noting that Hume the confirmed agnostic met his death with stoical calm and peace; Johnson the confirmed Christian was terrified of what lay beyond and clung tenaciously to his last breath.

At 144 pages of text, this book is a nice short introduction to one of the great minds of the 18th (indeed any) century. Read this before moving on to a more doorstop-sized biography like Ernest Mossner’s The Life of David Hume (Oxford, 1980).

Jefferson and Madison: The Great Collaboration by Adrienne Koch. This book was first published in 1950 and is a very lucid and readable introduction to one of the great friendships in American history. The Jefferson-John Adams friendship is more famous for the correspondence carried on by those twin titans in their last years, but the Jefferson-Madison partnership was more influential across Jefferson’s lifetime in shaping his ideological convictions and the political thought and policies that evolved from them. Madison grounded Jefferson in some of his more theoretical notions, like his idea that the Earth belongs to the living, and that therefore debts should be cancelled every 19 years or so. Maybe so, Madison said, but when do you start counting? And what do you do about debts that are sometimes contracted for and that benefit posterity, like wars? Besides applying the brakes to Jefferson’s philosophical whims, Madison was also simply a good and caring friend. It was for good reason that Jefferson told him, just months before his death, “to myself, you have been a pillar of support thro’ life. Take care of me when dead, and be assured that I shall leave with you my last affections.” Koch wrote extensively about the thought of the founders in a career cut short (she died in 1971 at age 59), and this one is well worth reading.

Jefferson and Madison: The Great Collaboration by Adrienne Koch. This book was first published in 1950 and is a very lucid and readable introduction to one of the great friendships in American history. The Jefferson-John Adams friendship is more famous for the correspondence carried on by those twin titans in their last years, but the Jefferson-Madison partnership was more influential across Jefferson’s lifetime in shaping his ideological convictions and the political thought and policies that evolved from them. Madison grounded Jefferson in some of his more theoretical notions, like his idea that the Earth belongs to the living, and that therefore debts should be cancelled every 19 years or so. Maybe so, Madison said, but when do you start counting? And what do you do about debts that are sometimes contracted for and that benefit posterity, like wars? Besides applying the brakes to Jefferson’s philosophical whims, Madison was also simply a good and caring friend. It was for good reason that Jefferson told him, just months before his death, “to myself, you have been a pillar of support thro’ life. Take care of me when dead, and be assured that I shall leave with you my last affections.” Koch wrote extensively about the thought of the founders in a career cut short (she died in 1971 at age 59), and this one is well worth reading.

The Great Books: Wuthering Heights by Charlotte Brontë (1847), Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1813), and The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane (1895).

The Great Books: Wuthering Heights by Charlotte Brontë (1847), Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1813), and The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane (1895).

The first two books were written by two of the most prominent authors of the nineteenth century, and all three of these offerings (like most good novels) have been variously plundered by Hollywood. Having seen the 1939 version of Wuthering Heights starring Merle Oberon and Lawrence Olivier—and never having read or seen any dramatized version of Pride and Prejudice—I was anxious to read both.

I liked Brontë’s much better. My only memory of the movie is Heathcliff and Catherine sitting on the moors, the night wind blowing through Oberon’s hair. Their literary counterparts are much darker and disagreeable people than I remember them being on screen, but perhaps I need to watch it again. Heathcliff and Catherine are two of literature’s most famous lovers, yet they are dismally unappealing  characters whose relationship is not a linear progression but is instead a twisting, page-turning tale of friendship, obsession, revenge, cruelty, sometimes implacable hatred, and deep and abiding love. The Brontës were a brooding and somber lot, and this book fully embodies that. Perfect autumn reading.

characters whose relationship is not a linear progression but is instead a twisting, page-turning tale of friendship, obsession, revenge, cruelty, sometimes implacable hatred, and deep and abiding love. The Brontës were a brooding and somber lot, and this book fully embodies that. Perfect autumn reading.

Austen, I must confess, disappointed me. This is obviously an important book in the history and development of the novel as a literary art form, but I am utterly confounded as to how it has provided so much fodder for both the big and small screen. I understand the tension between Elizabeth and Darcy, but almost nothing happens in these pages of any consequence. There’s a lot of letter-writing, talking, drinking tea, and heart-fluttering over whether Mr. Darcy or some other charming but equally dull fellow has feelings for someone, followed by someone thinking about writing letters, talking, drinking tea, or heart fluttering. (I found the Heathcliff-Catherine relationship much more compelling.)The most interesting character to my mind was Mr. Bennett, Elizabeth’s father, in part because he had a nice study in which to retreat from the rest of the members of his family, most of whom he can barely tolerate and from which he needed to escape, and often.

As to Crane’s much-lauded book about the essence of personal courage, somehow I avoided having to read this in K-12. Most poor souls did not. I can see now why so many people hate reading once they graduate from high school. The book’s most redeeming quality is that the covers are not very far apart.

Autobiography: Pride and Negligence: The History of the Boswell Papers by Frederick Pottle (McGraw-Hill, 1982) and Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763, ed. by Frederick Pottle (McGraw-Hill, 1950).

Autobiography: Pride and Negligence: The History of the Boswell Papers by Frederick Pottle (McGraw-Hill, 1982) and Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763, ed. by Frederick Pottle (McGraw-Hill, 1950).

“I am lost without my Boswell.” So says Sherlock Holmes about Dr. Watson in “A Scandal in Bohemia.” James Boswell is most famous as the author of the monumental biography, The Life of Samuel Johnson, first published in 1791 and never out of print. I bought a nice Easton Press edition in three volumes a few years back and loved it. Boswell is best known as Johnson’s biographer, but he was a fascinating and complex man in his own right, well worthy of our attention, and his published journals are just the place to start.

Boswell would be well at home in today’s world of social media. He kept extensive journals throughout his life, covering the most intimate details of his private goings-on and detailed transcriptions of his conversations with the great men of eighteenth-century Britain, including Georgia’s founder James Edward Oglethorpe, Samuel Johnson of course, the artist Joshua Reynolds, actor David Garrick, writer Oliver Goldsmith, the aforementioned David Hume, Voltaire, and many, many others. And just like today’s most avaricious Tweeters and Facebook-posters, he held nothing back, even when he probably should have. He wrote about everything: politics, art, literature, court intrigues, his sexual and sensual escapades (including cavorting with London’s  prostitutes and contracting and living with an STD), the peccadilloes of his friends and associates, falling out with his father over his chosen career, his fear of ghosts, and everything else you can imagine. He was an inveterate sinner who feared damnation but would walk out of a church and have sex with a prostitute. Sometimes he would miss the sermon because he was lusting over a woman in another pew. It is about as good a revealing snapshot of everyday life in eighteenth-century Britain—and a man driven by and forever at war with his passions—as we are ever likely to have, and it is all fascinating, a ripping good read.

prostitutes and contracting and living with an STD), the peccadilloes of his friends and associates, falling out with his father over his chosen career, his fear of ghosts, and everything else you can imagine. He was an inveterate sinner who feared damnation but would walk out of a church and have sex with a prostitute. Sometimes he would miss the sermon because he was lusting over a woman in another pew. It is about as good a revealing snapshot of everyday life in eighteenth-century Britain—and a man driven by and forever at war with his passions—as we are ever likely to have, and it is all fascinating, a ripping good read.

Boswell died in 1795 at age 54, leaving behind a wealth of personal papers and journals that he hoped would one day be published. His family, however, had other ideas. Generations of his descendants thought his writings inappropriate and scandalous, detailing as they did his every whim, fancy, and indiscretion. They were also ashamed of their association with a man whom they considered to have lowered himself by acting the sycophant to the overbearing and boorish Johnson simply to obtain material for his biography.

Boswell’s descendants didn’t exactly lose his writings, but it’s safe to say they put them away and mostly forgot about them as they passed from generation to generation. They were “rediscovered” in the 1920s and 30s in a croquet box at Malahide Castle in Ireland and in a stable loft at the home of a Scottish laird at Fettercairn House near Aberdeen. The story of the Boswell Papers’ disappearance and re-discovery is told in fascinating if sometimes excruciating details in Frederick Pottle’s Pride and Negligence: The History of the Boswell Papers. Pottle was a lifelong Boswell scholar and edited, in the Boswell Factory at Yale, all but one of the thirteen volumes of the popularly published journals that begin with the London Journal.

When Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763, was first published in 1950, it was a surprising best seller and one can see why. It’s racy and titillating, gossipy and erudite, introspective and philosophical, witty and just plain fun. There are two famous scenes in these pages: Bozzy’s first meeting with Johnson on May 19, 1763, of course, but also the memorable day when he confronts his girlfriend Louisa as to whether she knowingly gave him a venereal disease: “Madam, I have had no connection with any woman but you these two months. I was with my surgeon this morning, who declared I had got a strong infection, and that she from whom I had it could not be ignorant of it. Madam, such a thing in this case is worse than from a woman of the town, as from her you may expect it. You have used me very ill. I did not deserve it.” Louisa protested her innocence, but to no avail. Boswell stormed out and ended the relationship. Later in a quieter moment he confessed to his journal that he’d had this same disease twice before, but if he ever apologized to poor Louisa, the journal is silent.

Boswell kept on writing till his last days, and though his father scolded him for keeping “a register of his follies and communicat[ing] it to others as if proud of them,” we are the ultimate beneficiaries. There are twelve other volumes after this one and I look forward to reading them all.

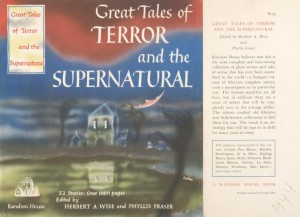

Bedtime Reading: Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural, ed. by Herbert A. Wise and Phyllis Fraser (Modern Library, 1944). October’s darker days and the coming of Halloween always put me in the mood for stories that explore that tenuous ground between light and shadow that Rod Serling made so famous, that creepy place where we’ll encounter, as the editors write in their splendid introduction, the “rips or gaps in the impalpable curtain that divides the natural world of our experience from all the tremendous mystery that lies beyond.”

that lies beyond.”

I’ve written at length about the genre, and this year I dipped into this fine compendium that comes in at over a thousand pages. The first part, the Great Tales of Terror, comprises almost a third of the book, and includes some real gems: Ambrose Bierce’s “The Boarded Window” with its chilling twist ending; Thomas Hardy’s “The Three Strangers,” a weird tale of 19 people gathered in a shepherd’s cottage and what happens when three unknown men wander in off the moor; “The Interruption” by W.W. Jacobs, about a man who poisons his wife and then lives in fear of his housekeeper, who knows he did it; Geoffrey Household’s “Taboo,” a tale of the ancient fear of werewolves; and the forgotten classic by Carl Stephenson, “Leiningen versus the Ants,” first published in Esquire in 1938, about what happens to a man who refuses to abandon his plantation in the face of an invading army of voracious insects. This section contained other tales by H.G. Wells, Conrad Aiken, and, surprisingly, Faulkner and Hemingway.

The editors caution the reader that “too generous a ration of horror may defeat its intended purpose, and succeed only in creating a surfeit instead of a feast.” They were right. Preferring to save the supernatural for next October, after feasting on the tales of terror, I stopped.

Which it’s time to do with this column. Next up: War and Peace. Turn the page and enjoy the upcoming winter.

The World War II movie has been around as long as the war itself. Hollywood began churning out anti-Nazi flicks even before combat began in Europe in 1939, and from the moment Japanese bombs fell on Pearl Harbor Tinseltown was all in. Some of its best efforts, like Casablanca, weren’t even about war, but about how the conflict disrupted lives and displaced lovers.

The World War II movie has been around as long as the war itself. Hollywood began churning out anti-Nazi flicks even before combat began in Europe in 1939, and from the moment Japanese bombs fell on Pearl Harbor Tinseltown was all in. Some of its best efforts, like Casablanca, weren’t even about war, but about how the conflict disrupted lives and displaced lovers. intensity never seen before, and no movie made after it can hope to pretend to anything other than farce if it doesn’t measure up.

intensity never seen before, and no movie made after it can hope to pretend to anything other than farce if it doesn’t measure up.

rookie who a) has never seen combat), b) is usually anti-violence and loathe to kill, no matter the circumstances and c) becomes the squad egghead and/or resident sissy who quotes poetry or will be seen reading a book of some kind during a lull in combat. This fellow’s manhood will be questioned, will be found wanting, will be put to the ultimate test, and he will, in the end, be the only one standing.

rookie who a) has never seen combat), b) is usually anti-violence and loathe to kill, no matter the circumstances and c) becomes the squad egghead and/or resident sissy who quotes poetry or will be seen reading a book of some kind during a lull in combat. This fellow’s manhood will be questioned, will be found wanting, will be put to the ultimate test, and he will, in the end, be the only one standing.

ank movie ever made? Nope. Since this is a blog about history, my money is still on Humphrey Bogart’s 1943 classic, Sahara, which employed all the buddy war-movie clichés but with a United Nations cast, and with Bogart’s ultra-cool, towering performance that still stands over 70 years later. Every generation needs to interpret World War II for itself and let its stars stand in for those of yester-year, whether it was Bogart, George C. Scott as Patton, Clint Eastwood in the Vietnam-era Kelly’s Heroes, Tom Hanks, and now Brad Pitt.

ank movie ever made? Nope. Since this is a blog about history, my money is still on Humphrey Bogart’s 1943 classic, Sahara, which employed all the buddy war-movie clichés but with a United Nations cast, and with Bogart’s ultra-cool, towering performance that still stands over 70 years later. Every generation needs to interpret World War II for itself and let its stars stand in for those of yester-year, whether it was Bogart, George C. Scott as Patton, Clint Eastwood in the Vietnam-era Kelly’s Heroes, Tom Hanks, and now Brad Pitt.

Last fall I decided rather late in the game to run the Rock & Roll Half Marathon but didn’t have anyone to run with. Most people who had run it before that I knew would have nothing to do with it again. They had better sense, which is why I of course approached Will one night in the gym and asked him if he’d run it with me. He said, “I haven’t run at all since I ran the Half last year.” I waited. He grinned. “I’d love to run it with you.” That’s the kind of person he was. As far as I could tell, he didn’t train much at all, if any. He even bought a new pair of running shoes the week before the race and planned to wear them, another no-no. The day before the race I drove over to the Savannah Convention Center to pick up my race packet, and as I was walking in, Will was walking out. He was in scrubs, I was in a suit. I realized later that it was the only time I’d ever seen Will when he wasn’t sweating. Will being Will, he gave me a big hug and wouldn’t stop talking about how sharp I looked in the suit. We finalized our plans for the next morning. I would drive to his house at 5 a.m. His friend and fellow doctor, Lee, would meet us there and we’d drive downtown together.

Last fall I decided rather late in the game to run the Rock & Roll Half Marathon but didn’t have anyone to run with. Most people who had run it before that I knew would have nothing to do with it again. They had better sense, which is why I of course approached Will one night in the gym and asked him if he’d run it with me. He said, “I haven’t run at all since I ran the Half last year.” I waited. He grinned. “I’d love to run it with you.” That’s the kind of person he was. As far as I could tell, he didn’t train much at all, if any. He even bought a new pair of running shoes the week before the race and planned to wear them, another no-no. The day before the race I drove over to the Savannah Convention Center to pick up my race packet, and as I was walking in, Will was walking out. He was in scrubs, I was in a suit. I realized later that it was the only time I’d ever seen Will when he wasn’t sweating. Will being Will, he gave me a big hug and wouldn’t stop talking about how sharp I looked in the suit. We finalized our plans for the next morning. I would drive to his house at 5 a.m. His friend and fellow doctor, Lee, would meet us there and we’d drive downtown together.