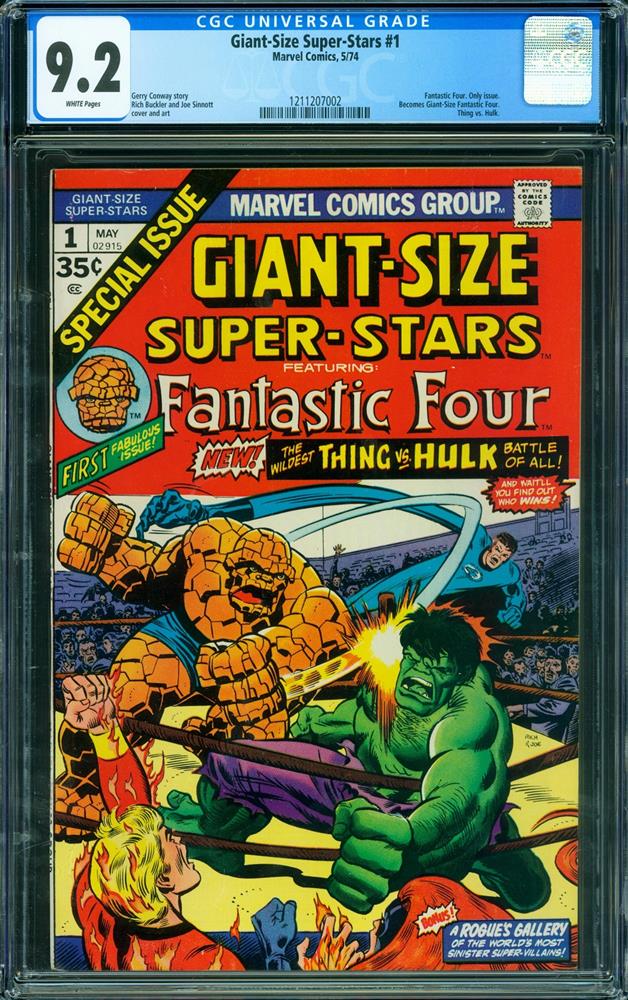

John Ferling, Winning Independence: The Decisive Years of the Revolutionary War, 1778-1781 (Bloomsbury, 2021, 701 pp., $40)

John Ferling, professor emeritus of history at the University of West Georgia, is one of the most prolific historians writing today—and one of the best. This is John’s 15th book on the colonial and Revolutionary period, and his 10th in the last 21 years. This volume, covering the last three years of the American Revolutionary War, weighs in at 561 pages of text and nearly 150 pages of notes and bibliography.

Long-suffering readers and listeners of Off the Deaton Path know that John and his work have been featured no less three times before, including a two-part interview.

By my count, this is John’s third book that focuses on the military phase of the Revolution, following Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (Oxford, 2007), and Whirlwind: The American Revolution and the War That Won It (Bloomsbury, 2015). Of course his biographies of George Washington and John Adams cover the war years as well, as does his political history of the war, A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic (Oxford, 2003), and his prosopography, Setting the World Ablaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the American Revolution (Oxford, 2000). Yet he never repeats himself, always offering fresh insights and interpretations.

How does he manage to do this? Here’s what I wrote in a review of his dual biography, Jefferson and Hamilton: The Rivalry That Forged a Nation (Bloomsbury, 2013): “How, one might ask, does Ferling keep plowing the same ground and still have something new to say? Part of it is simply attributable to his maturity as a scholar. Unlike others who leap from one time period to another with each book, Ferling has spent his entire professional life laboring in the vineyard of the Founding era. Ferling isn’t just dabbling in this period; he knows it as well as anyone can who is now two centuries removed from the time about which he’s writing. He is well versed in what the Founders wrote, what they read, what they believed, and what they hoped to achieve. But he’s not awe-struck by them. Simultaneously, his reflections on people and events have deepened with the years, as he himself has aged. As should happen as we grow older, his own insights about human nature reflect his growth as a human being; he’s more empathetic, more forgiving of human foibles and less harsh on their failures, though he isn’t afraid to point them out and to hold men and women accountable for not only what they achieve, but what they fail to achieve. He knows what it’s like to live life, make mistakes, and have regrets. It’s the primary reason why people in their 20s shouldn’t write biographies.”

Rick Atkinson, the author of The British Are Coming: The War for America, 1775-1777 (Henry Holt, 2019), the first volume of his Revolutionary Trilogy, recently told me that he believes some subjects are bottomless. No matter how much is written about some historical periods and people, historians hundreds of years from now will still be producing books on Abraham Lincoln, the Second World War, and the American Revolution.

John Ferling’s masterful prose, in this and all his books, bears this out. As prolific as John is, I have no doubt that other volumes will follow, all exquisitely written, exhaustively researched, and deeply analytical.

Americans are endlessly fascinated by those who fought and won the Revolution, and that first greatest generation has no finer historian than the indefatigable Dr. John Ferling.