As long-suffering readers of this blog know well, I’ve had a long love affair with the Rolling Stones. I’ve seen them nine times in five different cities over the last 35 years, from the first time as a 17-year-old senior in high school to the last as a 50-year-old in the summer of 2015.

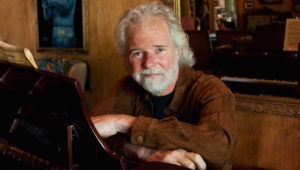

So imagine how Fan-Boy crazy I went when the Stones’ legendary keyboardist, Chuck Leavell, attended the Georgia Historical Society’s Trustees Gala in February in Savannah and yours truly got to sit with him at dinner. To say that I busted his chops would be an understatement. Turns out, he’s a huge fan of public television and was familiar with my own work on “Today in Georgia History.”

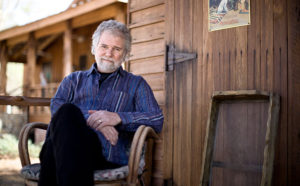

I first met Chuck for a few minutes when he gave the inaugural Mark Finlay Memorial Lecture  on environmental history at Armstrong State University in the spring of 2015. As you may know, Chuck and his wife Rose Lane turned her family’s plantation into a model tree farm outside Macon, and to say they’ve been good at it would be an understatement. They were jointly named National Outstanding Tree Farmers of the Year in 1999, and Chuck is the only two-time recipient of the Georgia Tree Farmer of the Year Award. The dedicated conservationist is the co-founder, with Joel Babbit, of the Mother Nature Network. In 2012 Chuck received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy for his work with the Allman Brothers Band as well as an Honorary Ranger award from the US Forest Service. Who else has done that? Take that Bob Dylan, with your Nobel Prize.

on environmental history at Armstrong State University in the spring of 2015. As you may know, Chuck and his wife Rose Lane turned her family’s plantation into a model tree farm outside Macon, and to say they’ve been good at it would be an understatement. They were jointly named National Outstanding Tree Farmers of the Year in 1999, and Chuck is the only two-time recipient of the Georgia Tree Farmer of the Year Award. The dedicated conservationist is the co-founder, with Joel Babbit, of the Mother Nature Network. In 2012 Chuck received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy for his work with the Allman Brothers Band as well as an Honorary Ranger award from the US Forest Service. Who else has done that? Take that Bob Dylan, with your Nobel Prize.

The husband, father, and grandfather is also an accomplished author of four books: Forever Green: The History and Hope of the American Forest; the autobiographical Between Rock and a Home Place; The Tree Farmer (a children’s book); and Growing A Better America.

Besides his work with the Allman Brothers, Chuck’s recorded with Eric Clapton, George Harrison, the Black Crowes, Blues Traveler, Train, John Mayer, and many others, in addition to his own accomplished solo projects. The Alabama native attended the Georgia Historical Society’s Gala to honor Pete Correll, the longtime chief of Georgia Pacific and board member of the Mother Nature Network, who was appointed by Governor Deal and GHS as a Georgia Trustee this year.

Besides his work with the Allman Brothers, Chuck’s recorded with Eric Clapton, George Harrison, the Black Crowes, Blues Traveler, Train, John Mayer, and many others, in addition to his own accomplished solo projects. The Alabama native attended the Georgia Historical Society’s Gala to honor Pete Correll, the longtime chief of Georgia Pacific and board member of the Mother Nature Network, who was appointed by Governor Deal and GHS as a Georgia Trustee this year.

As in our first encounter, Chuck couldn’t have been more gracious. He is, in the words of Keith Richards, a gentleman through and through and as modest as they come. You’d never know he was at the heart of the Greatest Rock n’ Roll Band in the World, their keyboardist, erstwhile musical director, and the man who counts them in to nearly every song. Having been a Stones fan long before he became their keyboardist, Chuck in many ways is Mr. Everyman, standing in for all of us who love the band and their music dearly while spending the better part of a lifetime getting a nightly rear view—as Charlie Watts once indelicately put it—”of Mick’s bum wigglin’ about.”

And how’s this for coincidence: he made his debut with the Stones at their Atlanta concert in the Fox Theater on October 26, 1981—the first Stones concert I ever attended. Through the magic that is the internet, you can hear the soundboard recording of that magical night here.

Without letting Chuck eat his dinner, I quizzed him about all things Stones, from how they stay so amazingly able to perform at such an advanced age (Mick exercises his body and voice relentlessly and rigorously watches his diet; Keith smokes and drinks), to Ronnie Wood’s newborn twins (for whom he’s given up smoking), to how long it’s all going to last. How do they first contact him to invite him to go on tour–does he look down at his cell and see Mick calling? (Sometimes, perhaps, but first the Stones’ manager Joyce Smyth sends out an email.) And so it went, on and on through every course. He answered my questions from the mundane to the sublime with unwavering politeness and an empty stomach.

Without letting Chuck eat his dinner, I quizzed him about all things Stones, from how they stay so amazingly able to perform at such an advanced age (Mick exercises his body and voice relentlessly and rigorously watches his diet; Keith smokes and drinks), to Ronnie Wood’s newborn twins (for whom he’s given up smoking), to how long it’s all going to last. How do they first contact him to invite him to go on tour–does he look down at his cell and see Mick calling? (Sometimes, perhaps, but first the Stones’ manager Joyce Smyth sends out an email.) And so it went, on and on through every course. He answered my questions from the mundane to the sublime with unwavering politeness and an empty stomach.

Many of my questions had to do with what they will and will not play live in concert, and why. As the group’s official “musical director” Chuck sets every show’s set list with Mr. Jagger and fights hard for songs that get rehearsed but rarely played live, like “Get off My Cloud” (hear Mick ask Chuck to count them in), “Lady Jane” and “Play with Fire.”

When I asked him why they don’t play early 60s standards like “Mercy, Mercy,” or “Walkin’ the Dog” live, he just laughed. He replied that people pay a lot of money to see them (don’t I know it!), and Mick and company feel they have to strike a delicate balance between playing familiar tunes like “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” that casual fans expect to hear, leaving little room for rarely played gems such as “She’s a Rainbow” and “Monkey Man” (both, incidentally, containing some of Chuck’s best work) for hard-core nuts like me.

Here’s what Chuck won’t tell you, though if you’ve followed the Stones during his tenure, you know it’s true: he’s made them a much better live band than they were before his arrival. They’re more professional, the songs are crisp and tight, giving their shows an energy and quality they lacked when everything was noticeably more ragged. In my opinion he’s a huge reason the band still plays to sold out audiences around the world well into their seventies.

know it’s true: he’s made them a much better live band than they were before his arrival. They’re more professional, the songs are crisp and tight, giving their shows an energy and quality they lacked when everything was noticeably more ragged. In my opinion he’s a huge reason the band still plays to sold out audiences around the world well into their seventies.

Chuck and Rose Lane have recently purchased a home in Savannah (not far from my office) and will be spending time here, so we’ll be neighbors for a few weeks each year.

The next sunny afternoon you stroll around Forsyth Park, you may see an unassuming white-haired, tree-farmer-looking gent walking beside you. If you pay him no mind and look the other way, you will miss the man who has been an integral part of musical history for the last third of a century and a well-respected member of rock royalty.

Take it from me: he won’t mind if you walk up and say, in Mick’s immortal words, “Please allow me to introduce myself….”

Tell him Stan said hello. And for all the pleasure—dare I say Satisfaction–you’ve given us through the years, Chuck, a heartfelt and sincere thank you. I like it, like it, yes I do.