Come all you no-hopers, you jokers and rogues

We’re on the road to nowhere, let’s find out where it goes

It might be a ladder to the stars, who knows?

Come all you no-hopers, you jokers and rogues.

Port Isaac’s Fishermen’s Friends, “No Hopers, Jokers, and Rogues”

Hello again. As long-suffering and loyal readers of this blog (both of them) well know, it’s been eight long months since my last entry. There are many reasons for that silence, some of which I’ll write about in the New Year—my involvement in the national discussion about Confederate memorials and iconography in public spaces, three glorious Rolling Stones concerts this summer, not one but two GHS public programs about Leo Frank in the summer and fall, the Georgia History Festival Kickoff lecture in October on the real Mad Men and the world they created, and a host of other things that make my job so interesting. As the year draws to its close, it seemed like a good time to say a quick hello and goodbye to 2015, to take stock of the year, take a peek at what might lie ahead, and to set a few goals for the New Year. A few musings at the end of the year, in no particular order:

Hello again. As long-suffering and loyal readers of this blog (both of them) well know, it’s been eight long months since my last entry. There are many reasons for that silence, some of which I’ll write about in the New Year—my involvement in the national discussion about Confederate memorials and iconography in public spaces, three glorious Rolling Stones concerts this summer, not one but two GHS public programs about Leo Frank in the summer and fall, the Georgia History Festival Kickoff lecture in October on the real Mad Men and the world they created, and a host of other things that make my job so interesting. As the year draws to its close, it seemed like a good time to say a quick hello and goodbye to 2015, to take stock of the year, take a peek at what might lie ahead, and to set a few goals for the New Year. A few musings at the end of the year, in no particular order:

Sports: In a blog post from last January, I praised the high-flying Atlanta Hawks and wondered how far they’d go. The answer turned out to be the Eastern Conference finals, farther than they’d ever been, and in which they got swept by the far-better Cleveland Cavaliers. They’re looking good this year too, but the lack of a true big man may yet be their undoing. Stay tuned.

As you well know, the Falcons started out 5-0 and yet will not make the playoffs for the second straight year, having squandered that glorious start by losing six straight games. But let’s give Dan Quinn time to build his own team; better things ahead here.

As hard as it is to believe, I think the same is true of the Braves. They’ve traded everyone on the team who had talent except for Freddie Freeman, and they played stink-ola baseball for most of last season and undoubtedly will again in the one to come. But some analysts are now predicting that the recent trades—as painful as they’ve been—are setting the Braves up to be the next Kansas City Royals or Houston Astros, young teams on the rise and winning championships. Cheers to that. I lived through the not-too-shabby years in the 1970s and have no desire to do it again.

Finally, there’s the Mark Richt firing/mutual parting. I’ve been as vocal as anyone that it was high time for a change at UGA, but after the Dogs finished 9-3 this year I thought there was no way it would happen. But it did, among much angst and hand-wringing and gnashing of teeth. As is required whenever discussing Richt, we must first say that he is a nice guy. A great guy. A man who’s done great things at the University of Georgia. But I’ve always maintained that there are lots of coaches who could take Georgia’s talent and win 9 or 10 games. Let’s see if we’ve finally got one who can win 12 or 13.

And with the college football playoffs beginning tonight, as an unabashed SEC fan I say: Roll Tide.

Books: I’ve read many great books this year that enlightened, informed, and entertained. Here are just a few of the ones I’d recommend:

Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason (1794-95): Thomas Paine was an 18th-century equivalent of Donald Trump, a bomb-thrower extraordinaire who in just a few words could set the settled order of nature on its ear. Unlike Trump, Paine was a disciple of the Enlightenment and a fervent believer in breaking the chains that had bound men in body and mind since time immemorial. Whether in Common Sense, The American Crisis, or The Rights of Man, Paine was a caustic critic of anything that smacked of orthodoxy. This book, published in several parts beginning in 1794, was one of his last great works, but instead of kings and governments, he chose the biggest target of all: religion.

It is not for the faint of heart, a literary broadside against the belief in revealed religion and what he calls a “superstitious” belief in a supernatural being who created the Earth in seven days and continues to dabble in our daily affairs. He throws down the gauntlet right at the beginning: “I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.” Institutionalized religion, Paine argues, are “human inventions set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.”

Paine’s ideas weren’t new, but his engaging style of writing brought Deism down to the level of the common man and made it all the more dangerous and radical for that. His ideas are still terrifying to many people. After more than two hundred years, Paine’s ideas are still extremely unpopular and considered dangerous in much of the America of 2015 that fervently believes that this is a Christian nation and that our elected leaders should be Born Again. At a time when we’re having a broad discussion about the place and role of religion in our national lives, this is a great and timely read. Whatever your beliefs, it will, like all great books, challenge you to stand on new ground. I highly recommend it.

Charles Dickens, The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1836-37). You can never go wrong with Dickens. One of the great glories lying ahead of me in my life is the pleasure of reading all of his works, fiction and non-fiction alike. I’ve read Great Expectations, A Tale of Two Cities, David Copperfield, and of course many of his Christmas stories. Unencumbered by the thought process, as our NPR friends Click and Clack used to say, I think this one is the best of them all. Unlike many of Dickens’ books, it’s not depressing—except for the fact that he could write so well and with such penetrating insight into the human condition at the tender age of 24—and in fact is hilarious. Here are the exploits of Mr. Samuel Pickwick and his companions Tracy Tupman, Nathaniel Winkle, and Augustus Snodgrass—and the irrepressible and singular Samuel Weller—as they travel around England, meeting some of the most interesting characters ever conceived along the way—Alfred Jingle, the residents of Dingley Dell, Joe the Fat Boy, Mr. Wardle, and many others. This one is a feast that I’m still working on and not anxious to finish.

Clayton Rawson, Death from a Top Hat (1938): A classic locked-room mystery, the first of four featuring the Great Merlini, a magician and amateur sleuth. It’s exactly what it sounds like: a body is found in an apartment with all the doors and windows sealed. He was strangled but how did the murderer leave? One of the best locked-room mysteries ever and great nightly bedtime reading. The classic Dell paperback is hard to find but this and the others in the series are all available on Kindle. A great way to drift off to the land of Morpheus.

Washington Irving, Bracebridge Hall, or The Humorists (1822). I first dipped into this book sitting in my favorite swing by the side of Lake Trahlyta at Vogel State Park on a warm August afternoon, but I saved it for the cooler days and darker nights of November, for which it’s better suited. It’s a collection of Irving’s short stories published under his pseudonym Geoffrey Crayon and supposedly collected when Crayon visited his friend Frank Bracebridge for his wedding in England. It follows up The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, which first introduced the Bracebridge family (and which featured Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle as bonuses), and preceded Tales of a Traveller.The collection contains some of the classic descriptions of the English countryside and the people who live there that made Irving famous and features some of his best stories—”The Stout Gentleman,” “The Haunted House,” “The Storm Ship,” and “Dolph Heyliger” among them. As lauded as Irving is for “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” his other writings go mostly unread today, and they shouldn’t. When the leaves turn golden in November, I always reach for him.

Yes, I read history and biography too, fear not. In preparing for the Georgia History Festival Kickoff Lecture on “The Birth of the American Dream” and the real Mad Men who created it, I reread David Halberstam’s The Fifties (1993). Halberstam is above all else a reporter and storyteller, and his descriptions of the people and events of that decade are exceptional. For a more detailed historical study, I turned to a volume in the Oxford History of the United States series, James Patterson’s Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (1996). Both of these books clock in at over 800 pages, so they aren’t light reading, but they’re both well worth your time. You can’t hurry through them and you don’t want to. Linger in the land of Lucy, Elvis, and The Bomb.

Reaching back to an earlier period, I also read Edward Larson’s The Return of George Washington, 1783-1789 (2014), coupled with the first volume of James Thomas Flexner’s classic multivolume biography of Washington, George Washington: The Forge of Experience, 1732-1775 (1965). Surprisingly, given the fame of Flexner’s set and his authoritative position in the Washington canon, I preferred Larson’s elegant and graceful prose, covering a period of Washington’s life that is often overlooked, the years between the American Revolution and his presidency. Larson convincingly argues that without Washington’s backing there never would have been a Constitution, demonstrating the enormous influence he had on the final document just by his presence in the room. Highly recommended.

This past year certainly hasn’t lacked for materials for the historian who plies his trade in the public realm. From the ISIS atrocities that bore eerie similarities to events in this country a century ago when African Americans were burned alive, mutilated, and lynched, to the mass shooting in Charleston that led to a national discussion of the role of Confederate iconography in American life, to the rise of Donald Trump, an egomaniacal “strongman” with echoes in Huey Long, Joseph McCarthy, and George Wallace, there has been plenty to comment on and write about as we try to sort out and make sense of the events in our daily lives and their historical antecedents. This next year will bring more of the same no doubt, as we enter a presidential election year that promises to be one of the most interesting and pivotal in our nation’s history. More on all of this anon.

Turn off your engines and slow down your wheels

Suddenly your master plan loses its appeal

Everybody knows that this reality’s not real

So raise a glass

To all things past

And celebrate how good it feels.

Port Isaac’s Fishermen’s Friends, “No Hopers, Jokers, and Rogues”

Next Year: For the New Year, I certainly have goals, if not resolutions. Any time of the year is a good time to set a goal (just like any day is a good day to start a diet), but since the New Year is the traditional time for clean slates, we’ll play along.

In 2016, I want to be more patient, especially with my daughter but also with everyone in my life, including the jerk in the car in front of me who’s driving too slow, or the maroon (as Bugs Bunny said) in the car behind me who wants me to drive faster.

Next year I hope to be more empathetic and sympathetic towards other people and their daily struggles and concerns. In memory of my friend Will, I need to pay more attention to the silent sufferings of other people.

Next year I’d like to find the courage to spend at least one hour every week visiting people that I don’t know in nursing homes and assisted living centers. They are among the most depressing places on Earth and are usually shunned by everyone who doesn’t need to go there. It’s hard to go there. And that’s one reason I’d like to start trying, to visit and spend time with people who have no one to talk to. I hope I have the courage to do it, and having written it down here in this public blog, perhaps I will. It’s a goal for 2016.

I’m so glad that he let me try it again

Cause my last time on earth I lived a whole world of sin

I’m so glad that I know more than I knew then

Gonna keep on tryin’

Till I reach my highest ground

Stevie Wonder, “Higher Ground”

I have the usual goals next year that I have every year: Exercise more. Run more. Read more. Write more. Listen more. Hike more. Bike more. Talk less. Eat less. Complain less. Argue less. Get angry less. Watch TV less (except for “Better Call Saul,” “Fargo,” and the upcoming “X Files”). To pick up the phone and talk to someone I haven’t talked to in a long time. To renew friendships and make new ones. To try on a daily basis, as Thomas Jefferson so eloquently put it, to take life by the smooth handle. To meet life and its challenges and opportunities with stoicism. To try, as Marcus Aurelius said, to arise each morning and remember what a precious privilege it is to be alive.

I have the usual goals next year that I have every year: Exercise more. Run more. Read more. Write more. Listen more. Hike more. Bike more. Talk less. Eat less. Complain less. Argue less. Get angry less. Watch TV less (except for “Better Call Saul,” “Fargo,” and the upcoming “X Files”). To pick up the phone and talk to someone I haven’t talked to in a long time. To renew friendships and make new ones. To try on a daily basis, as Thomas Jefferson so eloquently put it, to take life by the smooth handle. To meet life and its challenges and opportunities with stoicism. To try, as Marcus Aurelius said, to arise each morning and remember what a precious privilege it is to be alive.

To one and all who have read a single word or every word of this blog since it began on October 15, 2013, and who have supported me along the way and given me a word of encouragement, thank you. I’ll see you here much more frequently in 2016. Cheers to you all.

The World War II movie has been around as long as the war itself. Hollywood began churning out anti-Nazi flicks even before combat began in Europe in 1939, and from the moment Japanese bombs fell on Pearl Harbor Tinseltown was all in. Some of its best efforts, like Casablanca, weren’t even about war, but about how the conflict disrupted lives and displaced lovers.

The World War II movie has been around as long as the war itself. Hollywood began churning out anti-Nazi flicks even before combat began in Europe in 1939, and from the moment Japanese bombs fell on Pearl Harbor Tinseltown was all in. Some of its best efforts, like Casablanca, weren’t even about war, but about how the conflict disrupted lives and displaced lovers. intensity never seen before, and no movie made after it can hope to pretend to anything other than farce if it doesn’t measure up.

intensity never seen before, and no movie made after it can hope to pretend to anything other than farce if it doesn’t measure up.

rookie who a) has never seen combat), b) is usually anti-violence and loathe to kill, no matter the circumstances and c) becomes the squad egghead and/or resident sissy who quotes poetry or will be seen reading a book of some kind during a lull in combat. This fellow’s manhood will be questioned, will be found wanting, will be put to the ultimate test, and he will, in the end, be the only one standing.

rookie who a) has never seen combat), b) is usually anti-violence and loathe to kill, no matter the circumstances and c) becomes the squad egghead and/or resident sissy who quotes poetry or will be seen reading a book of some kind during a lull in combat. This fellow’s manhood will be questioned, will be found wanting, will be put to the ultimate test, and he will, in the end, be the only one standing.

ank movie ever made? Nope. Since this is a blog about history, my money is still on Humphrey Bogart’s 1943 classic, Sahara, which employed all the buddy war-movie clichés but with a United Nations cast, and with Bogart’s ultra-cool, towering performance that still stands over 70 years later. Every generation needs to interpret World War II for itself and let its stars stand in for those of yester-year, whether it was Bogart, George C. Scott as Patton, Clint Eastwood in the Vietnam-era Kelly’s Heroes, Tom Hanks, and now Brad Pitt.

ank movie ever made? Nope. Since this is a blog about history, my money is still on Humphrey Bogart’s 1943 classic, Sahara, which employed all the buddy war-movie clichés but with a United Nations cast, and with Bogart’s ultra-cool, towering performance that still stands over 70 years later. Every generation needs to interpret World War II for itself and let its stars stand in for those of yester-year, whether it was Bogart, George C. Scott as Patton, Clint Eastwood in the Vietnam-era Kelly’s Heroes, Tom Hanks, and now Brad Pitt.

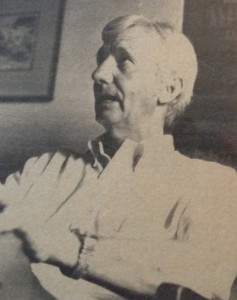

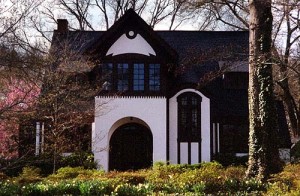

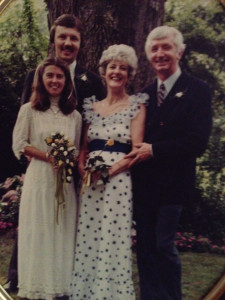

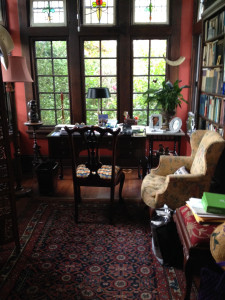

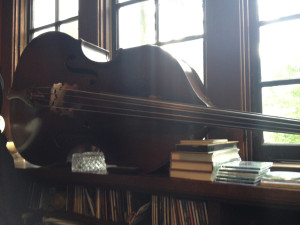

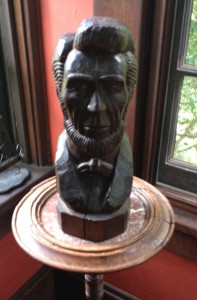

ie (all pictured below, left, at Vip’s 1982 wedding). I visited his beautiful Tudor-style historic home on W. Cloverhurst Avenue (at right), perused the book-lined shelves in his study, sat in his reading chair in the writing nook that he built in the backyard (reminiscent of writer Christopher Morley’s famous similar retreat, the Knothole), and walked the well-manicured grounds of Reggie’s beautiful gardens. Vip and I spent time in his father’s writing retreat that evening reminiscing over a glass of wine about his father and his own successful career as songwriter and musician. It was an emotional day of tribute to the good and gentle man who inspired me to choose the path of historian. Carl Jackson Vipperman was a great teacher, in the finest tradition of that honorabl

ie (all pictured below, left, at Vip’s 1982 wedding). I visited his beautiful Tudor-style historic home on W. Cloverhurst Avenue (at right), perused the book-lined shelves in his study, sat in his reading chair in the writing nook that he built in the backyard (reminiscent of writer Christopher Morley’s famous similar retreat, the Knothole), and walked the well-manicured grounds of Reggie’s beautiful gardens. Vip and I spent time in his father’s writing retreat that evening reminiscing over a glass of wine about his father and his own successful career as songwriter and musician. It was an emotional day of tribute to the good and gentle man who inspired me to choose the path of historian. Carl Jackson Vipperman was a great teacher, in the finest tradition of that honorabl e but too often undervalued profession. You will see why I was asked to speak in the remarks that follow, which I delivered at his memorial service:

e but too often undervalued profession. You will see why I was asked to speak in the remarks that follow, which I delivered at his memorial service: hardware store. There wasn’t much to go on, but I remember thinking that I might actually be able to do this college thing, and that I liked Carl Vipperman. I didn’t know it at the time, but that day was for me one like Dickens described, a memorable day that made great changes in me and bound me with chains of gold and flowers.

hardware store. There wasn’t much to go on, but I remember thinking that I might actually be able to do this college thing, and that I liked Carl Vipperman. I didn’t know it at the time, but that day was for me one like Dickens described, a memorable day that made great changes in me and bound me with chains of gold and flowers.

pirited, ugly business, with nasty backbiting and turf wars that can hurt feelings and leave friendships and reputations destroyed. Carl Vipperman was living proof that one can rise above all of that, and live one’s life with honor and integrity while treating others with kindness and respect. He told us in class one day that our lives would last longer than our careers, to fill it with things like community, culture, conversation and friends. Service to others. Absorption in things other than self is the secret to a happy life, well-rounded and well-lived, like Carl Vipperman’s. I regret that I didn’t go to greater lengths to see him and spend time with him in these latter years, but I’m grateful that at the end of the day he knew how much he meant to me and the influence he had on my life.

pirited, ugly business, with nasty backbiting and turf wars that can hurt feelings and leave friendships and reputations destroyed. Carl Vipperman was living proof that one can rise above all of that, and live one’s life with honor and integrity while treating others with kindness and respect. He told us in class one day that our lives would last longer than our careers, to fill it with things like community, culture, conversation and friends. Service to others. Absorption in things other than self is the secret to a happy life, well-rounded and well-lived, like Carl Vipperman’s. I regret that I didn’t go to greater lengths to see him and spend time with him in these latter years, but I’m grateful that at the end of the day he knew how much he meant to me and the influence he had on my life.