Once again this year, in celebration of the spooky season Stan reads a favorite ghost story, “Rats” by the master of the genre, M.R. James, first published in 1929. Also, this week in history and a dark day in Mayberry. Draw near the fire, dim the lights, and enjoy…..

Category Archives: Television

Q&A: Reading and Writing with Alexander Byrd

Alexander X. Byrd is an Associate Professor of History at Rice University. In 2020 he was appointed Rice’s first Vice Provost for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. Dr. Byrd’s area of expertise is Afro America, especially Black life in the Atlantic world and the Jim Crow South. He received his Ph.D. in History from Duke University in 2001. His study of free and forced transatlantic Black migration in the period of the American Revolution, Captives and Voyagers: Black Migrants Across the Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic World (LSU Press, 2010), received the 2009 Wesley-Logan Prize in African Diaspora History. Dr. Byrd teaches courses in African-American history at Rice, where he is a four-time recipient of the George R. Brown Award for Superior Teaching. He is currently co-editing the Oxford Handbook of African American History with Dr. Celia Naylor.

What first got you interested in history?

The first blame must go to good teachers who were also good story tellers. Well-stocked school and public libraries and the librarians who staffed were also at fault. Also, the stories on which I grew up that most sparked my imagination were historical in nature—between Alex Haley’s Roots and NBC’s Ba Ba Black Sheep—that had to have had some effect too.

What kind of reader were you as a child? Which childhood books and authors stick with you most?

As I child in Colorado Springs, I read every book in the school library on World War II. Maybe I missed a few. Still, when I moved to Houston (at about eleven years old), there were no books on the subject at my school or in my branch of the public library that I hadn’t already read. I recall having to re-read The Battle of Britain. By the sixth grade, I was on to Michael Herr’s Dispatches (1977) but by then I was also falling out of reading about war.

What book did you read in grad school that you never want to see again—and what book was most influential?

There are ways in which I’m still wrestling with Melville J. Herskovit’s The Myth of the Negro Past (1941), Sidney Mintz and Richard Price’s The Birth of African American Culture: An Anthropological Approach (1992), and Nathan Huggins’s Black Odyssey: The African-American Ordeal in Slavery (1977). Mary Karasch’s Slave Life in Rio de Janeiro, 1808-1850 (1987), Jan Vansina’s Paths in the Rainforest (1990),and George Brook’s Landlords and Strangers: Ecology, Society, and Trade in Western Africa, 1000-1630 (1993) were also quite influential. Wait, you said one book. There were so many great books!

What’s the last great book you read, fiction or non-fiction?

I am a fan of Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (2016).

When you’re not reading for your particular field of history, what else do you like to read? What genres do you avoid? And what’s your guilty reading pleasure?

Uh oh. Everything I read is related to my work. But I stream with the captions on. So I count that as recreational reading, and lately I’ve leaned toward sci-fi, alternative history, and super heroes on screen: Black Lightning, Raised by Wolves, The Expanse, The Man in the High Castle, Luke Cage. I should stop answering this question.

What do you read—in print or online—to stay informed?

The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Republic, the Houston Chronicle, and the New York Review of Books. But I still feel terribly under informed and uninformed. Maybe I don’t read the news as carefully as I used to. But I also have this feeling that there is news out there that I can’t find—that there is a universe of online writing that I haven’t and can’t tap into.

Describe your ideal reading experience (when, where, what, how).

All day in a full house of Byrds with brief stops for espresso, some stretches, sweets, and maybe a pizza.

What’s your favorite book no one else has heard of?

I assume that I’m always a few years behind everyone else.

What book or collection of books might people be surprised to find on your shelves?

To save the other Byrds from embarrassment, I can’t say. I don’t think that people would suspect, though, that I had Robert Alter’s translations of the Hebrew Bible here and there.

Disappointing, overrated, just not good: What book did you feel as if you were supposed to like, and didn’t? Do you remember the last book you put down without finishing?

Writing is hard. I try to be patient with writers. So when I put a book down, it’s usually less out of disappointment and more out of my schedule getting out of hand. There’s a good book barely under my bed, and another on my night stand that I need to return to.

What book would you recommend for America’s current moment?

This is not a bad time to pick up Cathy Park Hong (Dance Dance Revolution, 2007, and Engine Empire, 2012) and Hanif Abdurraqib (The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, 2016, They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, 2017, Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes on a Tribe Called Quest, 2019, A Fortune For Your Disaster, 2019).

What do you plan to read next?

Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (2020).

What is the next book you’re going to write?

A story of three Houston schools that speaks to the inequities and promise of public education now. I’ve been writing this book too long (and it’s too short to have taken this long). But I also think that parts of it are pretty good. It’s a book about schools, but to write it, I’ve done more research on parking garages than I ever thought I’d have occasion to do.

When and how do you write?

Not enough. But I’m learning to fit it in however and whenever I can. It’s taken me too long to learn this lesson.

With which three historic figures, dead or alive, would you like to have dinner?

I never have a good answer to this question. One of the great things about being a historian is that one is forever having dinner, or coffee, or breakfast with historic figures dead or alive.

Dispatches From Off the Deaton Path: The Twilight Zone

This week Dr. Deaton looks back at one of the most iconic TV shows in history, on the anniversary of the death of creator Rod Serling.

What I’m Reading Now: April 3, 2019

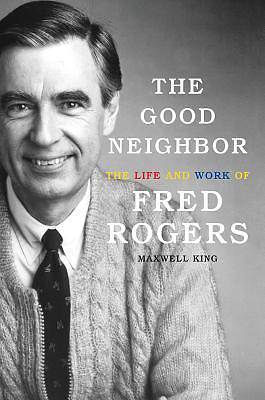

Maxwell King, The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers (Abrams, 2018, 405 pp.)

Fred Rogers as a child was bullied, chased home from school, and taunted as “Fat Freddy.” An only child, he sought refuge in the attic of his parents’ home, where he created his own world with puppets that he made. Why, he wondered, couldn’t the other kids see past his outward appearance to find out what he was really like? His parents and grandparents told him to “let on that you don’t care” how the other kids treated him. This would disarm them and show his indifference. He later wondered, “I didn’t have any friends and yet I was supposed to act like that didn’t bother me?” Children, he thought, deserved better than that.

Many years later, in his office at Pittsburgh’s WQED, where he and others produced his famous television show, Mister Rogers kept a framed plaque: “What is Essential is Invisible to the Eye.” It’s not what we see of other people–their face, their weight, their hair or clothes–that truly matter, but what’s inside them. It was a mantra that he lived by his entire life, shaped through the trauma of his own childhood, the love of parents and grandparents who instilled a lasting sense of service to others, and a strong Presbyterian faith.

Like many people of my generation, I watched “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” nearly every day when I was little, and I loved it. I was fascinated by the Neighborhood of Make Believe and wanted desperately to visit it, to see King Friday XIII, Lady Elaine Fairchilde, Daniel Striped Tiger, X the Owl, Henrietta Pussycat, and Lady Aberlin, on whom I lavished my first crush. Having my own puppets and later my own line of comics (written, drawn, and edited by yours truly), I spent a great deal of time in my own Neighborhood of Make Believe.

(Sidebar: The OCD part of me always worried that he wouldn’t get his sweater on and his sneakers tied before he came to the end of the opening song. Little did I know, till I read this book, that his musicians were right there on set with him and could time the song to his actions. Whew.)

The other thing I learned from Mister Rogers besides the power of imagination was that it was okay to be just who I was, inside and out. It didn’t matter the color, gender, or religion of his viewer, he wanted you as his neighbor. A powerful message then and now.

With the publication of this book, coinciding with the 2018 documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, and the upcoming bio-pic You Are My Friend starring Tom Hanks, Fred Rogers is more relevant than ever. Fifteen years after his death we seemingly need him again, with civility, kindness and tolerance stretched to the breaking point in our fractured and dysfunctional society. The simple lessons that he taught and lived are more potent and necessary with each passing day.

To be sure, he had his faults. Mister Rogers could be petulant at times when he didn’t get his way and was baffled as to how to raise his own two boys once they reached adolescence (his wife Joanne discovered their marijuana stash growing in the basement). But that only helps to humanize a man who would otherwise seem too Christ-like to be real. Still, despite these all-too-human foibles, he was, according to those who met him in person, very much the man he appeared to be on TV–authentic, caring, and always, always, kind.

He also had an unexpected sense of humor. One of my favorite stories in the book was when Fred Rogers and his wife were picked up at the airport and during the drive to the next destination, on a cold and rainy night, the car ran out of gas. The driver had to flag down a passing State Trooper, who put the Rogers and their belongings in his car. The driver groaned and asked Mr. Rogers, “what would Lady Elaine [one of the show’s puppets] say in this situation?” Out of the darkness he heard Rogers in Lady Elaine’s voice reply, “She’d probably say, ‘Oh shit!'”

I find it difficult to read about Fred Rogers–or to watch him–without channeling his behavior. And that’s not a bad thing. To wit: while reading this book, I drove to work one morning, and in my haste to get through a stop sign to secure a scarce parking spot, I failed to look both ways and almost ran into an older man who was crossing the street from my right. I suddenly saw him out of the corner of my eye and could hear him yelling at me through the car window.

I slammed on the brakes and he crossed behind me. As he came around the car, his face flush with anger, I rolled my window down.

Pre-Fred-Rogers Stan, impatient and late for work, at this point might have called this fellow a name that would have implied that his parents weren’t married. But I could hear Mister Rogers’ voice in my head: “There are three ways to accomplish success: first, be kind; second, be kind, third, be kind.”

“I’m so sorry,” I said, “I didn’t see you.” He wasn’t expecting that. “Well,” he barked and sputtered, “look both ways next time, okay?”

In as friendly a voice as I could muster, with nary a hint of sarcasm, I replied, “Yes sir, I sure will. I’m awfully sorry.” He looked perplexed and turned on his heel and walked off.

Fred Rogers believed, as his biographer so eloquently puts it, that human kindness will always make life better. Such a simple lesson, but one that struggles to be heard through the noise and anger of modern society.

“When I was a boy,” he said, “I used to think that strong meant having big muscles, physical power; but the longer I live, the more I realize that real strength has much more to do with what is not seen. Real strength has to do with helping others.”

Need inspiration? Pick up this book, watch the above-mentioned documentary, or simply go online and watch a few of his shows.

Then pick up his standard and carry it forward. It’s not too late to make it a beautiful day in the neighborhood.