So my end-of-the year wrap-up blog is over two weeks late. That’s in part because I took a moment to enjoy the four days of cold weather that descended upon Savannah two weeks ago. Have no fear, this isn’t going to descend into another rant about the weather, but winter this year in Savannah was apparently scheduled for the four days surrounding that weekend, and I paused to enjoy it. It’s now spring again, here in mid January. Air-conditioners are running, trees are blooming, and grass will soon be growing and in need of trimming. Atlanta missed a record high on Christmas Eve by one degree, and came perilously close on Christmas Day. That’s two years in a row that bathing suits have been more in order at Yuletide than sweaters, and yours truly doesn’t like it. I don’t like it all. Okay, so it turned into a short rant about the weather. Sorry.

One good thing about delaying this column is that it gives me a chance to congratulate the Atlanta Falcons for winning their division, locking up the second seed in the NFC playoffs, a first-round bye, and a divisional win over the Seattle Seahawks. The rematch with the Green Bay Packers in this weekend’s NFC championship game will be a good one. Stay tuned.

We can also congratulate the Clemson Tigers on knocking off the top-ranked Alabama Crimson Tide (after shutting out Ohio State) and winning the college football national championship. It’s not easy to beat Urban Meyer and Nick Saban, as Clemson did in this year’s playoff. The Tigers needed nearly all 60 minutes to beat Bama, but when it was over they had won their first national title in 35 years, thanks in large part to Gainesville native Deshaun Watson. How the Georgia schools let him get away is beyond me, but there he was wearing orange and purple and standing on the championship stage afterward. My prediction: Bama will be back in the playoff next year, and Clemson will be at home watching, with Watson and lot of other talent moving on. Everyone else has to rebuild; Saban just reloads and starts shooting again.

We can also congratulate the Clemson Tigers on knocking off the top-ranked Alabama Crimson Tide (after shutting out Ohio State) and winning the college football national championship. It’s not easy to beat Urban Meyer and Nick Saban, as Clemson did in this year’s playoff. The Tigers needed nearly all 60 minutes to beat Bama, but when it was over they had won their first national title in 35 years, thanks in large part to Gainesville native Deshaun Watson. How the Georgia schools let him get away is beyond me, but there he was wearing orange and purple and standing on the championship stage afterward. My prediction: Bama will be back in the playoff next year, and Clemson will be at home watching, with Watson and lot of other talent moving on. Everyone else has to rebuild; Saban just reloads and starts shooting again.

Another Goodbye to Another Good Friend: If you’re on social media at all, then you know that 2016 went down as one of the most unpopular years in recent memory, if we could take votes on such things. It was certainly a bad year for deaths in the entertainment industry, as you no doubt noticed yourself and as many other people have pointed out. The deaths of David Bowie, Prince, Glenn Frey, and many others left a huge void, and they’ve all been lovingly remembered and mourned on cultural and social media. There were many other famous passings, from Muhammad Ali to Nancy Reagan.

But lost among all those big names were some lesser stars in the firmament that you may or may not have heard of but should have. We’ll pause for a moment here and take one last look back at some other folks who shook off this mortal coil in 2016:

Though you may have missed it, Thomas Jefferson died in 2016, 190 years after his first death. Okay, so it wasn’t that Jefferson. But all the millions of fans of the movie musical 1776—of which I happen to be one—fondly remember Ken Howard’s lighthearted portrayal of Thomas Jefferson, long before he became The White Shadow on TV. The Tony- and Emmy-award-winning Howard died on March 23 at age 71.

Though you may have missed it, Thomas Jefferson died in 2016, 190 years after his first death. Okay, so it wasn’t that Jefferson. But all the millions of fans of the movie musical 1776—of which I happen to be one—fondly remember Ken Howard’s lighthearted portrayal of Thomas Jefferson, long before he became The White Shadow on TV. The Tony- and Emmy-award-winning Howard died on March 23 at age 71.

Horace Ward, born in LaGrange, Georgia, was the first African American to attempt to batter down the wall of segregation that prevented black students from attending the University of Georgia. In 1950 he applied to UGA Law School and was turned down, despite a stellar undergraduate career at Morehouse and Atlanta University. Ward tried and failed for nearly a decade to overturn the decision in court, but his case helped eventually to end segregation at Georgia’s flagship university after 175 years, when Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter were admitted in 1961. Ward went on to become the first African American ever to serve on the federal bench in Georgia, though he shamefully had to go elsewhere to earn his law degree. Judge Horace Taliaferro Ward died at the age of 88 on April 23 and is buried in Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery.

Horace Ward, born in LaGrange, Georgia, was the first African American to attempt to batter down the wall of segregation that prevented black students from attending the University of Georgia. In 1950 he applied to UGA Law School and was turned down, despite a stellar undergraduate career at Morehouse and Atlanta University. Ward tried and failed for nearly a decade to overturn the decision in court, but his case helped eventually to end segregation at Georgia’s flagship university after 175 years, when Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter were admitted in 1961. Ward went on to become the first African American ever to serve on the federal bench in Georgia, though he shamefully had to go elsewhere to earn his law degree. Judge Horace Taliaferro Ward died at the age of 88 on April 23 and is buried in Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery.

On April 22, 1945, Jerry O’Keefe of Ocean Spring, Mississippi, shot down five Japanese planes over Okinawa in his first aerial dogfight. He was 21 years old. After the war he went into the insurance business and became mayor of Biloxi, where—Mississippi born and bred—he faced down and arrested members of the Ku Klux Klan who marched there without a permit. The Klan sent him death threats and burned a cross on his lawn. The warrior who earned the Air Medal, the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Congressional Gold Medal died on August 23 at age 93.

On April 22, 1945, Jerry O’Keefe of Ocean Spring, Mississippi, shot down five Japanese planes over Okinawa in his first aerial dogfight. He was 21 years old. After the war he went into the insurance business and became mayor of Biloxi, where—Mississippi born and bred—he faced down and arrested members of the Ku Klux Klan who marched there without a permit. The Klan sent him death threats and burned a cross on his lawn. The warrior who earned the Air Medal, the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Congressional Gold Medal died on August 23 at age 93.

It took William H. McNeill ten years to write The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, but after its publication in 1963 it became a surprising best seller and won the National Book Award for history and biography. As Clifton Fadiman said, it is “deeply reflective, the work of a master scholar.” Hugh Trevor-Roper, no slouch himself, called it “the most learned…the most intelligent…the most stimulating and fascinating book that has ever set out to recount and explain the whole history of mankind.” It remains unsurpassed in scope and breadth, one of 20 books that McNeill wrote in a long and distinguished career. If you haven’t read it, you should. McNeill died on July 8 at 98.

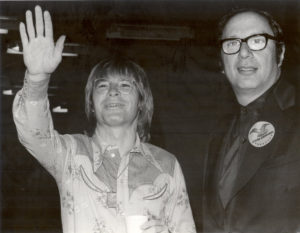

Andy Griffith fans everywhere (like me) have Richard Linke to thank for Griffith’s discovery and the TV show that brought him worldwide fame as the mighty sheriff of Mayberry. While working for Capitol Records, Linke was sitting by his radio one clear night in 1953 when he picked up a southern station broadcasting Griffith’s recording of “What it Was, Was Football.” Linke knew something special when he heard it. He flew immediately to North Carolina, bought the rights to the record for Capitol for $10,000, signed Griffith to a contract, and managed his career for the rest of his life. As Griffith put it, “had it not been for him, I would have gone down the toilet.” Linke died on June 15 at 98.

Andy Griffith fans everywhere (like me) have Richard Linke to thank for Griffith’s discovery and the TV show that brought him worldwide fame as the mighty sheriff of Mayberry. While working for Capitol Records, Linke was sitting by his radio one clear night in 1953 when he picked up a southern station broadcasting Griffith’s recording of “What it Was, Was Football.” Linke knew something special when he heard it. He flew immediately to North Carolina, bought the rights to the record for Capitol for $10,000, signed Griffith to a contract, and managed his career for the rest of his life. As Griffith put it, “had it not been for him, I would have gone down the toilet.” Linke died on June 15 at 98.

Producer and arranger Milt Okun performed a similar service for music fans. He helped create the Chad Mitchell Trio and when Mitchell left in 1965, Okun discovered and hired Henry John Deutschendorf, Jr. to replace him. Okun turned John Deutshchendorf into John Denver and produced and published the music that made him a folk and pop legend. The man who gave the world the musical gift of the Bard of the Rocky Mountains died on November 15 at age 92.

Producer and arranger Milt Okun performed a similar service for music fans. He helped create the Chad Mitchell Trio and when Mitchell left in 1965, Okun discovered and hired Henry John Deutschendorf, Jr. to replace him. Okun turned John Deutshchendorf into John Denver and produced and published the music that made him a folk and pop legend. The man who gave the world the musical gift of the Bard of the Rocky Mountains died on November 15 at age 92.

If you’re a fan of classic cartoons like me, you’ve heard the voice of Janet Waldo all of your life. She was the female Mel Blanc, bringing dozens of animated characters to life over the last 60 years, from Josie in “Josie and the Pussycats,” to Judy Jetson, Penelope Pitstop, and Fred Flintstone’s mother-in-law. She died on June 12 at the age of 96.

And if you’re a devotee of classic movies, one death last year was especially notable: Madeleine Lebeau was 19 years old when she was cast as Yvonne in Casablanca, and she achieved screen immortality by singing “La Marseillaise” with tears streaming down her face. When she died on May 1 at age 92, the French culture minister Audrey Azoulay said, “She will forever be the face of French resistance.” Lebeau was the last surviving credited cast member of what is arguably the best film ever made.

And if you’re a devotee of classic movies, one death last year was especially notable: Madeleine Lebeau was 19 years old when she was cast as Yvonne in Casablanca, and she achieved screen immortality by singing “La Marseillaise” with tears streaming down her face. When she died on May 1 at age 92, the French culture minister Audrey Azoulay said, “She will forever be the face of French resistance.” Lebeau was the last surviving credited cast member of what is arguably the best film ever made.

There were other “lasts” who died in 2016: Bill Herz was the last surviving crew member of Orson Welles’ “War of the Worlds” 1938 radio broadcast that terrified listeners with the news of Martians invading New Jersey. Herz died on May 10 at 99.

Two other big-screen deaths of note: Fritz Weaver was an all-purpose actor who appeared in dozens of movies and TV shows since the 1950s, but to my mind his most notable role was as the paranoid Air Force Colonel Cascio, who refuses to help the Russians shoot down American planes in the 1964 Cold War thriller Fail Safe. Diehard “Twilight Zone” fans will remember him from the episodes “Third From the Sun” and “The Obsolete Man.” He died November 26 at age 90.

Two other big-screen deaths of note: Fritz Weaver was an all-purpose actor who appeared in dozens of movies and TV shows since the 1950s, but to my mind his most notable role was as the paranoid Air Force Colonel Cascio, who refuses to help the Russians shoot down American planes in the 1964 Cold War thriller Fail Safe. Diehard “Twilight Zone” fans will remember him from the episodes “Third From the Sun” and “The Obsolete Man.” He died November 26 at age 90.

Similar to Weaver, Frank Finlay had a long and distinguished career across the stage and screen, but every Christmas he returns as Jacob Marley’s ghost in the 1984 George C. Scott version of A Christmas Carol, the best of them all, in my humble and uninformed opinion. Finlay died on January 30 at 89.

Similar to Weaver, Frank Finlay had a long and distinguished career across the stage and screen, but every Christmas he returns as Jacob Marley’s ghost in the 1984 George C. Scott version of A Christmas Carol, the best of them all, in my humble and uninformed opinion. Finlay died on January 30 at 89.

The 1990s TV show “Homicide: Life on the Street” was groundbreaking television and is considered by many to be one of the best shows ever produced. I happen to be one of those people.  One of the finest episodes was Season Three’s “Crosetti,” which explored the suicide of Detective Steve Crosetti and its devastating impact on his fellow officers. Jon Polito played Crosetti for only two seasons but he left an indelible mark on the show, as well as the numerous characters he created as a stock player in several Coen Brothers’ films, including The Big Lebowski. He also played Jerry and Kramer’s landlord in the Season Nine “Seinfeld” episode “The Reverse Peephole.” Jon Polito died on September 1 at age 65.

One of the finest episodes was Season Three’s “Crosetti,” which explored the suicide of Detective Steve Crosetti and its devastating impact on his fellow officers. Jon Polito played Crosetti for only two seasons but he left an indelible mark on the show, as well as the numerous characters he created as a stock player in several Coen Brothers’ films, including The Big Lebowski. He also played Jerry and Kramer’s landlord in the Season Nine “Seinfeld” episode “The Reverse Peephole.” Jon Polito died on September 1 at age 65.

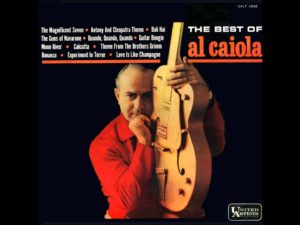

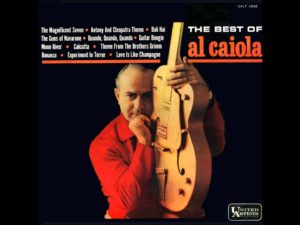

A personal memory: my mother had a wonderful and eclectic album collection when I was growing up, and one of my favorites was the steel guitar sounds of Al Caiola. You may think you don’t know him but you do: he recorded scores of instrumental versions of movie and TV show themes that became big hits and the soundtrack of a generation, most famously “The Magnificent Seven” and “Bonanza.” The next time you hear Paul Anka’s “Put Your Head on My Shoulder,” Neil Sedaka’s “Calendar Girl,” Bobby Darin’s “Mack the Knife” or “Splish-Splash,” Simon & Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson,” Johnny Mathis’ “Chances Are,” Del Shannon’s “Runaway” and Ben E. King’s “Stand by Me,” you’re listening to the great guitarist who died in a New Jersey nursing home on November 9. He was 96.

A personal memory: my mother had a wonderful and eclectic album collection when I was growing up, and one of my favorites was the steel guitar sounds of Al Caiola. You may think you don’t know him but you do: he recorded scores of instrumental versions of movie and TV show themes that became big hits and the soundtrack of a generation, most famously “The Magnificent Seven” and “Bonanza.” The next time you hear Paul Anka’s “Put Your Head on My Shoulder,” Neil Sedaka’s “Calendar Girl,” Bobby Darin’s “Mack the Knife” or “Splish-Splash,” Simon & Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson,” Johnny Mathis’ “Chances Are,” Del Shannon’s “Runaway” and Ben E. King’s “Stand by Me,” you’re listening to the great guitarist who died in a New Jersey nursing home on November 9. He was 96.

Finally, the man known to his legion of fans as The Hag died on his 79th birthday on April 6. As Keith Richards said, “One of the great country singers of all time and a helluva guitar player. Gonna miss you pal.”

Finally, the man known to his legion of fans as The Hag died on his 79th birthday on April 6. As Keith Richards said, “One of the great country singers of all time and a helluva guitar player. Gonna miss you pal.”

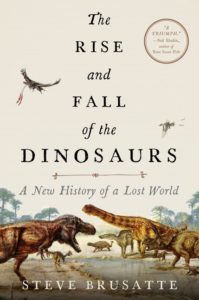

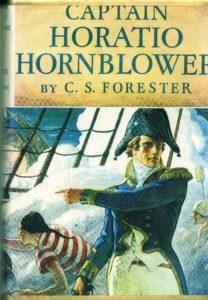

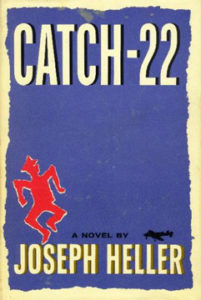

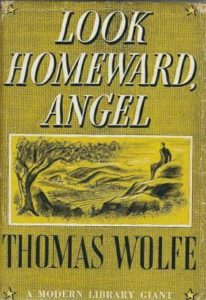

Literary Mountains Climbed: In 2016 I read 31 books totaling almost 12,000 pages. Among them were two that I’ve had on my list for a long time: War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, and Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel.

Tolstoy’s masterpiece, first published in 1869, is as advertised, one of the best books I’ve ever read. Don’t let its size daunt you: the version I read, Easton Press’s leather-bound edition in its series “The 100 Greatest Books Ever Written,” came in at 1,035 closely written pages. The Count of Monte Cristo and Les Miserables were both longer. It took me 45 days to read, an average of 23 pages a day. That’s easily doable, and most days I read closer to 30-40. It was well worth the time and effort.

Tolstoy’s masterpiece, first published in 1869, is as advertised, one of the best books I’ve ever read. Don’t let its size daunt you: the version I read, Easton Press’s leather-bound edition in its series “The 100 Greatest Books Ever Written,” came in at 1,035 closely written pages. The Count of Monte Cristo and Les Miserables were both longer. It took me 45 days to read, an average of 23 pages a day. That’s easily doable, and most days I read closer to 30-40. It was well worth the time and effort.

For all of its reputation, it’s not hard to read, and the Russian names are not hard to follow. The best advice I can offer is just start reading and keep at it; the names will sort themselves out in good time, and the story will carry you along. Tolstoy is not Dostoyevsky; he doesn’t drill down a thousand feet, he is not concerned with the abstract, the unconscious, or the abnormal. Tolstoy is focused on human life, in all its vastness and complexity, and that’s his real subject in this book. The book drops down into a group of people’s lives and it leaves them still struggling at the end. Along the way, you learn a lot about them, about the choices we all make as human beings—and you’ll learn about yourself as well. As literary critic Clifton Fadiman said so well, “once a few minor hazards are braved, this vast chronicle of Napoleonic times seems to become an open book, as if it had been written in the sunlight.” This is a timeless book with its own rhythm that will have a lasting effect on you long after you finish it, as all great books do. Read it like eating an elephant, one bite at a time. You will not regret it.

Thomas Wolfe’s “young-man-from-the-provinces” theme in his semi-autobiographical Look Homeward, Angel: A Story of the Buried Life (1929) will be familiar to anyone who’s read Stendahl’s classic The Red and the Black. Wolfe of course takes the genre to another level and inspired a host of writers since. I had long imagined Wolfe to be as impenetrable as William Faulkner, but in this I was completely wrong.

Thomas Wolfe’s “young-man-from-the-provinces” theme in his semi-autobiographical Look Homeward, Angel: A Story of the Buried Life (1929) will be familiar to anyone who’s read Stendahl’s classic The Red and the Black. Wolfe of course takes the genre to another level and inspired a host of writers since. I had long imagined Wolfe to be as impenetrable as William Faulkner, but in this I was completely wrong.

After reading A. Scott Berg’s Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, Berg’s award-winning biography of the legendary Scribner’s editor who tamed and cut Wolfe’s rambling prose down to size, I decided to tackle the novel and see for myself. Wolfe’s telling of Eugene Gant’s growing up to age 19 in Altamont, North Carolina, is a tour-de-force: ““By God, I shall spend the rest of my life getting my heart back, healing and forgetting every scar you put upon me when I was a child. The first move I ever made, after the cradle, was to crawl for the door, and every move I have made since has been an effort to escape.” The Gant family was, to put it mildly, dysfunctional before that word became stylish, and Wolfe spares no one. His real hometown of Asheville turned harshly on him when the novel was released because of his unsparing portrait, but he remains North Carolina’s most famous author. The first thing I did after I finished was to order the sequels: Of Time and the River, The Web and the Rock, and You Can’t Go Home Again, the latter two published after Wolfe’s untimely death at 37 in 1938.

Wolfe’s literary star has fallen since his death, unlike those of contemporaries Faulkner, Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In my uninformed opinion he towers over them all, and his books deserve to be more widely read. The title of this essay is perhaps the most famous passage from Wolfe’s first novel and the title he preferred for it. It was for good reason that critic Malcolm Cowley wrote that Wolfe was “the only contemporary writer who can be mentioned in the same breath as Dickens and Dostoevsky.”

Other Mountains Climbed in 2016: Last year in my end-of-year column I wrote that some of my 2016 goals were: “Exercise more. Run more. Read more. Write more. Listen more. Hike more. Bike more. Talk less. Eat less. Complain less. Argue less. Get angry less. Watch TV less. To pick up the phone and talk to someone I haven’t talked to in a long time. To renew friendships and make new ones. To try on a daily basis, as Thomas Jefferson so eloquently put it, to take life by the smooth handle. To meet life and its challenges and opportunities with stoicism. To try, as Marcus Aurelius said, to arise each morning and remember what a precious privilege it is to be alive.”

I succeeded in some areas (I exercised 316 days last year) and not so much in others. The list seems pretty good as I read over it again, so I’ll stick with it for this year. Whatever your goals and aspirations, I hope you succeeded in 2016.

To one and all who took the time to read a word of this blog last year—or any year—I offer my heartfelt thanks. Happy New Year, and I hope to see more of you here in 2017.

The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald (Scribner, 1925, 180 pp.)

The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald (Scribner, 1925, 180 pp.)