Nicholas Kristoff’s column in the February 16 edition of The New York Times about the irrelevancy o f academic scholars in the national discussion has set off quite a conversation among my academic friends on social media. His point is that the academy contains some of the greatest minds in the world today, but too many of them have voluntarily removed themselves from taking part in a larger discussion in the national arena and marginalized or even punished their colleagues who do.

f academic scholars in the national discussion has set off quite a conversation among my academic friends on social media. His point is that the academy contains some of the greatest minds in the world today, but too many of them have voluntarily removed themselves from taking part in a larger discussion in the national arena and marginalized or even punished their colleagues who do.

He quotes Will McCants, a Middle East specialist at the Brookings Institution: “academics frown on public pontificating as a frivolous distraction from real research. This attitude affects tenure decisions. If the sine qua non for academic success is peer-reviewed publications, then academics who ‘waste their time’ writing for the masses will be penalized.”

Even worse, the International Studies Association executive council proposed that its publication editors be barred from writing personal blogs like the one you’re reading now. As Kristoff writes, “The association might as well scream: We want our scholars to be less influential!”

As someone who works for a public history educational institution, I have a large stake in this conversation. The Georgia Historical Society bridges the gap between the academy and the public, taking the sometimes-esoteric findings of the profession and making them accessible, understandable, and relevant to a larger public. As Senior Historian, it’s my job to make sure that happens, and it’s a role I’ve come to relish. We try to incorporate the latest in cutting-edge historical research in everything we do, from public programs, to K-12 and college and university teacher training, historical markers, and the Today in Georgia History program. It’s one of the reasons that I write this blog. (That and it’s just so much fun.)

I spoke to the Rotary Club of Savannah last week about the controversy over removing statues and monuments and was introduced as, among other things, a “public intellectual.” Far be it from me to claim such a distinction, but I’m glad if others see me that way. It tells me that they do in fact see me playing a public role and contributing in a meaningful way in the discussion of issues and debates of our time. I have worked hard over the last 15+ years to build a respectable public history resume that demonstrates engagement with my peers in public history and in the academy, and with the public at large.

And I am unashamedly a public historian. When strangers ask me what I do for a living, I usually tell them I’m a historian, specifically a public historian. Not a professor, not a teacher, not an academic, but a public historian (though public historians are of course teachers). What does that mean? In the simplest of terms it means I get paid to think, talk, read, write, and talk about history in the public arena on behalf of an educational institution that has for its mission teaching the public about the past in order to create a better future.

I say “unashamedly” because when I finished my Ph.D. in history the University of Florida (pictured above) I was expected to get a job in the academy and teach and publish. When I didn’t, there was a palpable sense of disappointment among some of my professors, past and present. Not, I should say, among my UF peers—the men and women I went to grad school with there are among the finest minds and best people in the world.

Chris Olsen, Dan Kilbride, Mark Greenberg, me, Glenn Crothers (with son Colin), and Andy Chancey, November 2002

In fact, let me take a moment to give a shout-out to the Band of Brothers that I entered UF with in the fall of 1990, all gainfully employed in various jobs in history and the humanities: Andy Chancey, Glenn Crothers, Mark Greenberg, Dan Kilbride, and Chris Olsen. Andrew Frank and Lisa Tendrich Frank followed a couple of years later, and collectively they are some of the best historians I know—and seven of the best friends I am ever likely to have. They have all gone on to distinguish themselves in the profession and I’m proud to say that we always supported and encouraged each other in a way that I knew even then was unusual in the cut-throat world of academia.

From many others former colleagues and professors and from new acquaintances I’d meet at professional meetings, I kept getting the same questions in the years after graduation: when are you going to get a real (aka academic) history job? When are you going to come back to doing “real” history? It didn’t seem to matter that I had a job working in Savannah, one of the most beautiful places in the world, in a job that made me very happy. I wasn’t in the academy, doing “real” research, writing monographs, teaching undergrads, and there was a sense that I was wasting the training I had received. I was often treated by other professional historians in the academy condescendingly as the proverbial red-headed stepchild.

That isn’t the case anymore, I’m happy to say. Public history jobs are as desirable as academic ones in the ever-shrinking humanities job market, though there will always be those who turn their nose up at anyone working outside the academy or at those who seek to reach a wider audience beyond specialized journals and monographs.

For me personally, the rewards of the job after almost 16 years have far surpassed anything I could have imagined when I first started working at the Georgia Historical Society. I was hired to direct programs and publications, which at first meant planning and implementing our lectures and meetings and assisting with the editing and production of the Georgia Historical Quarterly. The job has happily grown far beyond that.

Through the years I’ve been fortunate to be able to shape the job in ways that have made it uniquely my own. I’ve dropped many of the duties that I first had while picking up others along the way. As Senior Historian, I serve as the chief academic officer of the institution, responsible for ensuring the scholarly quality and integrity of our brand through all of our educational initiatives, including public programs, publications, historical markers, teacher training initiatives, and public outreach.

If that sounds like the boiler plate off my job description, it is. But here’s what it means, directly relevant to the topic under discussion here: Above all else, it’s my job to make sure we’re connecting with a larger public in three important ways: 1) educating the public about the importance of history and the role it plays in our contemporary culture and society, 2) the role that GHS plays in serving as a bridge between the academy and the public and 3) how GHS serves as a national research center that facilitates the ongoing study of the past in order to ensure a better future.

None of this is what I thought I’d be doing when I was interviewing for academic jobs as I finished my dissertation. I thought I’d be teaching a heavy load of classes, grading blue books, and serving on various committees. Not that I would have minded any of that. I enjoyed doing all of it as a grad student and got great teaching evaluations from my students. But as a public historian, I’ve been able to do things and meet people in this job–writers, journalists, broadcasters, politicians, sports figures, entrepreneurs, Supreme Court justices, musicians, actors—that would have seemed impossible when I began. And very improbable if I’d followed the traditional path. I’ve been able to grow professionally in ways I couldn’t have imagined.

From the beginning of my tenure here at GHS in 1998, I’ve been fortunate to work for a boss, Todd Groce—himself a published, professional historian—who never minded when I got the spotlight and the publicity as long as I was making the Georgia Historical Society look good. And he understood that the more we were all out there, talking to and engaging with a larger public, the better history and GHS were being served.

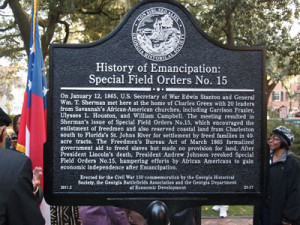

Consequently, from the moment I arrived here I starte d doing public speaking and haven’t ever stopped, becoming along the way the public face of a public history educational institution. I’ve spoken to every group imaginable at meetings, dinners, and luncheons, hosted televised round-table discussions, directed a half-dozen National Endowment for the Humanities summer workshops that trained hundreds of college and university professors from all over the country, written dozens of historical markers, helped with fundraising and donor cultivation, assisted with manuscript recruitment for our research center, conducted oral histories, and written editorials and book reviews for newspapers and other publications, including here in this blog.

d doing public speaking and haven’t ever stopped, becoming along the way the public face of a public history educational institution. I’ve spoken to every group imaginable at meetings, dinners, and luncheons, hosted televised round-table discussions, directed a half-dozen National Endowment for the Humanities summer workshops that trained hundreds of college and university professors from all over the country, written dozens of historical markers, helped with fundraising and donor cultivation, assisted with manuscript recruitment for our research center, conducted oral histories, and written editorials and book reviews for newspapers and other publications, including here in this blog.

And it was my supreme good fortune to serve as writer and host for Today in Georgia History when that opportunity came along, which garnered two Emmys. All of it has been enormously rewarding professionally and I’ve had a blast doing it.

I think Kristoff has missed the mark about my colleagues in the academy, too. They are almost all engaged in the larger community outside the walls of academe, and they use social and broadcast media to do it.

Some examples among people I know, all interested in different subjects: my friend Karen Cox at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, on her blog PopSouth: The South in Popular Culture, recently highlighted eight different blogs (including this one) being written by professional historians, and hers is one not to be missed.

Stacey Robertson serves as Oglesby Endowed Professor of American Heritage and the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Bradley University in Illinois. She writes about her work on women abolitionists and their meaning in contemporary culture, among many other things, at www.staceymrobertson.com.

My former grad-school mate Dan Kilbride, now at John Carroll University in Cleveland, is host of the webcast New Books in American Studies, a consortium of podcasts that introduces new scholarly books to a larger audience. Check out Dan’s latest interview with Michael O’Brien, editor of The Letters of C. Vann Woodward (which I reviewed here) and his own webpage for other interviews.

No scholar I know is more heavily engaged with the public than Heather Thompson at Temple University, whose findings about the historical and cultural implications of mass incarceration have landed her on nearly every media outlet in the country. She’ll be even more widely seen and heard when Pantheon Books publishes her new account of the Attica Prison Rebellion of 1971 and how it still reverberates in American society.

Finally, Doug Egerton, who teaches history at Le Moyne College in New York and serves on the editorial board of the Georgia Historical Quarterly, has spent his career speaking and writing for a broad audience. His recent editorial in the New York Times on the controversial Denmark Vesey statue in Charleston is a model for what all of us should be doing in both local and national media when we can.

All of these scholars, and many others too numerous to list here, are also on Facebook and Twitter.

The truth is, all professionally trained historians have a responsibility to talk to a larger audience, no matter where we work—on college campuses, libraries, in museums, national parks, or historical societies. There is a great hunger for history out there, and it is readily available now on the internet, but so much of it is just plain bad. Indifference about engaging a larger public isn’t just ignorant, it’s dangerous. All of us, in and out of the academy, have a responsibility to be engaged with a larger public because we cannot afford to cede the ground to others who would willfully distort the past for partisan ends.

Americans revere their history, but they need to get that history right, and they need trained, credentialed professionals to help them understand not history as some wish it had been, but as it actually was, based upon sound research in credible primary sources. It’s one thing to examine the evidence and come to disagreement over what it means. That’s the very essence of education. It’s another thing entirely to fabricate history out of whole cloth, like the myth of black Confederates. No one will ever be served by a pejorative, factually inaccurate distortion of the American past.

And the internet, as we all know, is full of self-anointed authorities. As writer Alexander Chee said in a recent New York Times editorial about everyone and anyone “contributing” to on-line encyclopedia articles, the belief that we all have a right to our own opinions has given way to a larger cultural problem, the belief that we also have a right to base those opinions on misinformation. As he put it, “I believe all information should be as democratically available as possible, but I’m averse to it being democratically produced.”

If we can ground our history in good, modern, sound and credible scholarship, that is the best foundation of all. And the best answer of all. All of us in the academy and in public history have a responsibility to engage with the wider world. No more turning our collective noses up or looking down on each other. Let’s join together and make our voices heard.