Check out this new video series from Off the Deaton Path where GHS’s Stan Deaton will explore the theme of the 2023-2024 Georgia History Festival: Governing Georgia Across Three Centuries. In part one of this series, Dr. Deaton talks about why we have government.

Category Archives: Government

Podcast S6E5: A Vow of Silence and the Mongolian Rhapsody

In this podcast Stan discusses the newly available Ed Jackson Collection at GHS, Freddie Mercury’s handwritten lyrics to “Bohemian Rhapsody,” Ed Ames’ tomahawk throw, and college students giving up their cellphones to take a vow of silence.

The Second Time is Never the Charm

President Joe Biden announced last week that he will seek a second term. For some, the power of the presidency is irresistible. Almost no one walks away voluntarily from seeking a second term. Lyndon Johnson was the last man who did in 1968, but only after Vietnam and domestic unrest combined to nearly destroy his presidency. And he was swept into office in one of the greatest landslides in history just four years earlier.

President Joe Biden announced last week that he will seek a second term. For some, the power of the presidency is irresistible. Almost no one walks away voluntarily from seeking a second term. Lyndon Johnson was the last man who did in 1968, but only after Vietnam and domestic unrest combined to nearly destroy his presidency. And he was swept into office in one of the greatest landslides in history just four years earlier.

Many presidents seek a second term to complete what they consider the unfinished business of the first term; in fact, the current incumbent used almost this exact language in announcing his bid for re-election. Only one president, James K. Polk, felt that he had completed everything he set out to accomplish when he stepped down willingly in 1849 after one term. His four years encompassed the annexation of Texas, the Mexican War, the dispute with Great Britain over the Oregon Territory, and the violent controversy over the westward expansion of slavery. The stress of it all contributed to Polk’s death at age 53, just three months after his term ended.

Historically, second terms are almost always disasters. From Washington to Barack Obama, almost every president who has served beyond four years came to grief on the rocky shoals of a second term. Political scandals, wars, assassinations, economic blunders, natural disasters, and foreign affairs (and sometimes domestic ones too, a la Bill Clinton) can quickly diminish popularity and political power, limiting a president’s leadership and ability to govern effectively.

Second-term woes go all the way back to our nation’s first president. George Washington agreed to seek a second term only after being persuaded to do so by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. Both men then promptly resigned and left Washington to preside over an increasingly divided country polarized by Jefferson’s Republicans and Hamilton’s Federalists.

Washington’s second term was bedeviled by diplomatic troubles with Great Britain—most notably the controversial Jay Treaty—and Revolutionary France. The day Washington left office he saw this vitriol directed at him in a Republican paper: “Would to God you had retired to private life four years ago. If ever a nation was debauched by a man, the American nation has been debauched by you.”

Thomas Jefferson’s first term was one of the most successful in American history—the Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the country and hastened the Federalist party into extinction—and his popularity propelled him into a second term. But it was a disaster, again thanks to the diplomatic tangle of European affairs. Jefferson’s Embargo Act of 1807, which basically stopped American shipping abroad, nearly ruined the American economy and was enormously unpopular. Jefferson practically fled the White House in 1809.

Most other presidents who served two terms fared no better. The British army chased James Madison out of Washington before burning the city during the War of 1812. Andrew Jackson was censured by the Senate in his second term during the Bank War, the one and only time that has happened.

Lincoln was assassinated in his second term (as was McKinley), but had he lived his reputation might have foundered on the shoals of Reconstruction, just as Andrew Johnson’s did.

U.S. Grant was a war hero but the scandals of his second term marked his presidency as one of the worst in history.

World War I and the fight over the League of Nations nearly killed Woodrow Wilson in his second term. FDR’s ill-advised court-packing scheme during his second term nearly derailed his presidency and had World War II not been looming on the horizon, his political fortunes would have dropped considerably. Civil rights unrest, Sputnik, the Cold War, and Castro’s rise in Cuba all managed to douse Dwight Eisenhower’s popularity in the last years of his second term.

During the last 50 years, second terms have all been fraught with peril: the afore-mentioned LBJ (technically not a second term, but close, after finishing out JFK’s term); Nixon and Watergate; Reagan and the Iran-Contra affair; Clinton’s impeachment; while the Iraq war, the fumbled response to Katrina, and the economic meltdown eroded George W. Bush’s popularity to record-setting lows. And while Obama’s second term was not marked by outright scandal, it is not difficult to see Donald Trump’s 2016 election as a stinging rebuke to his administration.

Perhaps the Confederates got this part right: they limited their President to one six-year term, period. No worries about re-election, and the Congress knows it will have to deal with the same president for the next six years.

So why seek a second term at all? There is something about the power of the presidency, the pinnacle of political power, that is hard to give up voluntarily. Only time will tell if the current occupant succeeds where others have not. But history is not on his side.

As Thomas Jefferson said about the presidency from personal experience: “No man will ever bring out of that office the reputation which carries him into it.”

The Law of Unintended Consequences

The Supreme Court’s decision was highly anticipated—and was leaked before the Court’s announcement. The Court would be ruling on the most contentious issue of the age, one that had threatened to tear the country apart for decades. When it was announced, one side hailed it as the final word on a divisive subject, finally laying the issue to rest. The other side exploded in moral outrage, charging the court with action far beyond its jurisdiction by trying to solve a complex and difficult political issue, overturning a long-standing precedent, and vowed to disregard the ruling and take the appeal directly to the American people.

The Supreme Court’s decision was highly anticipated—and was leaked before the Court’s announcement. The Court would be ruling on the most contentious issue of the age, one that had threatened to tear the country apart for decades. When it was announced, one side hailed it as the final word on a divisive subject, finally laying the issue to rest. The other side exploded in moral outrage, charging the court with action far beyond its jurisdiction by trying to solve a complex and difficult political issue, overturning a long-standing precedent, and vowed to disregard the ruling and take the appeal directly to the American people.

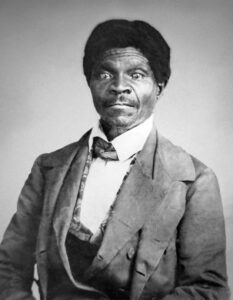

Sound familiar? It was March 6, 1857, and the case was Dred Scott v. Sanford. It has often been called by historians “the worst Supreme Court decision ever handed down.”

Dred Scott was an enslaved man who lived in Missouri (a slave state) with an Army surgeon, Dr. John Emerson. Emerson took Scott to the free state of Illinois and then on to the free territory of Wisconsin, where Scott married his wife, Harriet Robinson. Four years later they returned to Missouri with Emerson. After Emerson’s death, his widow refused to sell the Scotts their freedom. With the help of anti-slavery lawyers, Scott sued, claiming that his residence in Illinois and Wisconsin meant that he was free. The case worked its way through state courts. Mrs. Emerson eventually transferred Scott’s ownership to her brother, John Sanford, who lived in New York state, moving the suit into Federal jurisdiction. The case finally made its way to the Supreme Court, presided over by Chief Justice Roger Taney of Maryland.

Missouri applied for statehood in 1820 as a slave state, which would have upset the Congressional balance of power between free and slave states. Maine came in as a free state at the same time, but Congress, passing the Compromise, ruled that all future territories west of Missouri and north of Missouri’s southern border at latitude 36°30′ would be free. The Missouri Compromise had held for 37 years, even as the agitation over slavery in the western territories had fiercely divided the country.

The Taney Court, in a 7-2 decision, handed down its decision on March 6, just two days after pro-slavery Pennsylvania Democrat James Buchanan’s inauguration as the 15th president.

Taney could have ruled that Scott, being Black and enslaved, was not due his freedom and left it at that. But Taney went much further, ruling that Black Americans—whether enslaved or free—were not citizens, had never been citizens, and would never be, ignoring the precedent that African Americans were citizens in several states already. Not being citizens, he ruled, they had no standing to sue in any court in the United States and in fact had “no rights which any white man is bound to respect.”

Again, Taney and his majority could have stopped there. But Taney wanted to put an end to the acrimonious debates threatening to rend the Union asunder. He ruled that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 forbidding slavery in the western territories had been unconstitutional, that Congress never had the right to forbid or abolish slavery in any territory. Slavery followed the flag.

Associate Justice James Moore Wayne of Georgia played a large role in pushing the Court to go farther than simply issuing a narrow ruling. Hoping that the Court could do what politicians seemingly could not—settle the slavery question for good—Wayne was instrumental in persuading the Court to rule the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, and his concurring opinion went farther in supporting Taney’s than any other justice’s.

The White South embraced the decision as an answered prayer while a storm of anger swept across the North. Georgia’s Robert Toombs bragged that he would call the roll of his slaves under Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument, while abolitionists exploded in outrage when they read newspaper headlines that boasted, “The Triumph of Slavery Complete.” Northern Free-Soilers and champions of popular sovereignty—the right of citizens in each territory to decide the issue for themselves—thought the ruling a blow against democracy. Ultimately the decision split the Democratic Party into irreconcilable factions while uniting the nascent Republican Party in opposition to what it considered an outrageous case of judicial overreach that had no moral validity and insulted freedom-loving Americans everywhere.

The decision proved to be a disaster for the Supreme Court and the proslavery advocates who celebrated it. The Court’s reputation was damaged, and far from quelling the slavery issue, the decision backfired, pushing the country ever closer to Civil War. That conflict did exactly what Taney had denied possible: It destroyed slavery and, through the Reconstruction amendments, made citizens of the formerly enslaved, in the process forever altering the relationship between the Federal government and the American people.

The Black struggle for full citizenship during the era of Emancipation and Reconstruction would lead to the great Civil Rights revolutions of the 20th century—and, ironically, the heavily politicized Dred Scott case helped pave the way.

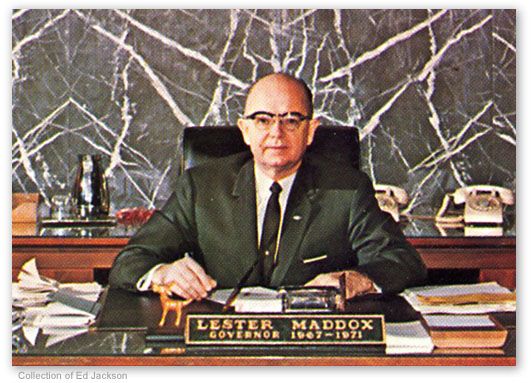

The Enigma of Lester Maddox

Earlier this week, my colleague Lisa “War Eagle” Landers, the GHS Education Coordinator, sent me a letter she had received from a middle school teacher, who asked:

“Do you know why Lester Maddox, once elected governor, chose to appoint so many African Americans to government positions given his strong record on segregation? It would seem he would favor an all-White government. I have done a lot of research on Lester Maddox trying to find that information with no luck. I have to think it was for self-gain.”

It’s a great question. Lisa asked me for a response, and I thought I’d knock out a quick reply. The answer turned out to be a bit more complicated than I thought.

It was one of the great ironies in Georgia history: Maddox had run for governor in 1966 on a segregationist, states-rights platform—despite & because of the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965—but then once in power he appointed more Black Georgians to positions in state government than any previous governor. He also desegregated the Georgia State Patrol, no small thing all by itself.

Every available source on Governor Maddox tells us these facts, but as I prepared my response for Lisa, I realized that the usual go-to sources don’t directly answer the question as to why. What was Maddox’s motivation?

Lester Maddox was the original Donald Trump. He campaigned as an outsider who loathed the establishment. He was a businessman with no political experience. He behaved in diametrically opposite ways from more button-downed establishment politicians. He hated the press but loved publicity. He made deliberately provocative statements to rev up his base. He labeled political opponents as not just wrong but as un-American socialists and communists. And no one gave him a chance of actually becoming governor.

As UGA history professor Numan Bartley explained in a 1974 Georgia Historical Quarterly article: “Sophisticated observers found it difficult to take Maddox seriously, given his reputation for antics and colorful fanaticism, but, like Eugene Talmadge before him, Maddox had a genuine appeal for the white common folks.”

Sound familiar?

Maddox, unlike Trump, came from very modest circumstances. He quit high school during the Great Depression to help support his family. As an outspoken segregationist, he had twice run unsuccessfully for mayor of Atlanta and Lt. Governor of Georgia. But Maddox had made a name for himself as the owner of The Pickrick cafeteria near Georgia Tech, where he steadfastly refused to serve Black customers, even after the passage of national Civil Rights laws that required him to do so. In July 1964 he even chased several Black Tech students out of his business with an ax handle, which soon became one of his popular public props. Maddox eventually sold his restaurant rather than integrate.

All of this, of course, made Maddox wildly popular with the many White Georgians who fiercely opposed the Civil Rights movement. When he ran for governor in the 1966 Democratic primary against the much more moderate Ellis Arnall, Maddox, according to Bartley, “projected a certain charisma with his earnest blend of social segregation and religious fundamentalism.”

Maddox held nothing back. In the words of the New York Times, Maddox’s openly racist platform “included the view that blacks were intellectually inferior to whites, that integration was a Communist plot, that segregation was somewhere justified in Scripture and that a federal mandate to integrate schools was ‘ungodly, un-Christian and un-American.’” The Ku Klux Klan wholeheartedly endorsed him.

Less than two years after the passage of two of the most far-reaching pieces of social legislation in American history, angry and resentful White Georgians were in no mood for moderation. Maddox won 64 percent of the rural vote, but only 41 percent of the urban, much as Trump would 50 years later. And like Trump, Maddox overwhelmingly won White working-class voters (70 percent in urban areas) but only about a quarter of more affluent Whites, and only 0.3 percent of the urban Black vote. In the general election, Republican Bo Callaway outpolled Maddox but didn’t gain a majority, throwing the contest into the Democratic-controlled House, where the ax-handle-wielding Maddox won easily.

As with the presidential election 50 years later, the establishment across the nation staggered in disbelief that the man pilloried as an outspoken clown had triumphed. Time magazine labeled him a “strident racist.” Newsweek dismissed him as a “backwoods demagogue out in the boondocks.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., said Maddox’s election made him ashamed to be a Georgian. Two years later, Governor Maddox refused to honor the martyred King by allowing his body to lie in state in Georgia’s Capitol, nor did he attend his funeral or lower state flags to half-mast.

Georgians and national observers braced for the publicity-seeking Maddox to roll back the clock and begin an all-out war of Massive Resistance to Civil Rights. But that didn’t happen.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia summarizes Maddox’s accomplishments thus: “Maddox proved reasonably progressive on many racial matters. As governor he backed significant prison reform, an issue popular with many of the state’s African Americans. He appointed more African Americans to government positions than all previous Georgia governors combined, including the first Black officer in the Georgia State Patrol and the first Black official to the state Board of Corrections. Though he never finished high school, Maddox greatly increased funding for the University System of Georgia.”

How to explain the enigma of Lester Maddox?

The traditional sources list these facts but offer little else. To gain more insight, I called two of Georgia’s most knowledgeable political insiders: Jim Galloway, a 40-year veteran of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the former lead writer and founder of the AJC’s Political Insider blog; and Keith Mason, Governor Zell Miller’s chief of staff.

They both readily agreed that whatever else Lester Maddox was, he was an astute politician with good instincts who hired highly qualified and capable people to fill administrative posts. The best of these was undoubtedly a teacher from north Georgia named Zell Miller, hired in 1969 to serve as Governor Maddox’s executive secretary, as the Chief of Staff position was known at that time.

It was Miller who pushed Maddox toward progressive policies regarding race and higher education, and Maddox was smart enough to listen. Galloway also suggested that however racist Maddox may have been at heart, he did not want to be remembered as a leader who took Georgia backward. Instead, looking toward a political future beyond the governorship, Maddox worked hard to build an image that was at odds with everything he had done to win the office. He was savvy enough to know that, though he may not like it, Black voters would play a prominent role in Georgia’s future, and he wanted to be able to point to substantive racial accomplishments during his administration. It turns out that even the brazenly outspoken Lester Maddox didn’t want to be remembered as nothing more than a bigot.

But that was Maddox the politician. Maddox the man changed very little. He endorsed George Wallace for president in 1968, called MLK an “enemy of our country” after his assassination, and ran for president himself in 1976 against Jimmy Carter (who Maddox called the most corrupt man he’d ever met). Though he never changed, Georgia did: voters rejected Maddox’s repeated attempts to regain Georgia’s governorship.

Till the end Lester Maddox denied to all who would listen that he was not and had never been racist in his life. Jim Galloway said that in every conversation he had with him, Maddox pushed back hard against any notion that there was anything to atone for. Still, he remained unapologetically committed to segregation till the day he died on June 25, 2003: “I want my race preserved, and I hope most everybody else wants theirs preserved. I think forced segregation is illegal and wrong. I think forced racial integration is illegal and wrong. I believe both of them to be unconstitutional.”

In 1999, the State of Georgia dedicated the Lester and Virginia Maddox Bridge, located on Interstate 75 in Cobb County, near Truist Park. Not surprisingly, the name has come under fire in the last year in the wake of the movement to remove controversial statues and names of White supremacists from public landmarks.

Who was Lester Maddox? Was he the man with the ax-handle who chased Black patrons from his restaurant? Or the man who broke the color barrier at the Georgia State Patrol and insisted that police officers address Black Georgians with respect?

Zell Miller, himself no stranger to charges of political inconsistency, believed that, “No man in Georgia public life has been more maligned, more misrepresented, or more misunderstood than Lester Maddox.”

Georgia is once again in the national spotlight: For the first time in its history, Georgia recently elected a Black man and a Jewish man to represent the state in the US Senate. Georgia also recently passed a controversial voting law that its advocates say promotes election integrity but has brought national scrutiny amid charges that the law aims to suppress minority votes.

Modern Georgia, like the legacy of Lester Maddox—indeed, like all of our history—is more complicated than we think.