In this podcast Stan discusses the newly available Ed Jackson Collection at GHS, Freddie Mercury’s handwritten lyrics to “Bohemian Rhapsody,” Ed Ames’ tomahawk throw, and college students giving up their cellphones to take a vow of silence.

In this podcast Stan discusses the newly available Ed Jackson Collection at GHS, Freddie Mercury’s handwritten lyrics to “Bohemian Rhapsody,” Ed Ames’ tomahawk throw, and college students giving up their cellphones to take a vow of silence.

We received word here at GHS this week of the death of our dear friend Ed Jackson on Tuesday, January 10, 2023, age 79.

We received word here at GHS this week of the death of our dear friend Ed Jackson on Tuesday, January 10, 2023, age 79.

The Kingsport, Tennessee, native grew up in Texas, but it was the people of Georgia and their history that he made his life’s work.

Ed went to the University of Mississippi in the early 1960s and received his B.A. in History and an M.A. in political science. He put both of those to good use when, in 1970, he arrived in Athens at the University of Georgia and began a long and distinguished career at the Carl Vinson Institute of Government, retiring as Senior Public Service Associate 40 years later, in 2010.

During those 40 years Ed became the acknowledged expert, the man to ask about Georgia history and government. He trained governors, legislators, state employees, mayors, civic organizations, teachers, students, authored textbooks, spoke extensively, published widely, compiled databases, created over fifteen websites, photographed every corner of our state, and collected anything and everything that he could get his hands on about Georgia history, from postcards, to photographs, maps, artifacts of all kinds, campaign signs, and everything beyond and between that could tell the story of Georgia and her people.

Here’s what I said about Ed in the GHS’s Headlines newsletter yesterday: “Ed Jackson’s knowledge of Georgia’s people and history was unparalleled. He was Georgia’s unofficial state historian, and all of us beat a path to his door to dip into that deep reservoir of learning. There was no subject related to Georgia that he didn’t know something about, and that he would gladly and freely share. Every conversation with him left you wiser. He was also a great friend to this institution, through his membership, his time and resources, and the knowledge that he shared through his writing and research. The Georgia Historical Society is honored to be the repository of the Edwin Jackson Collection, ensuring that his documentary legacy will live on and that his vast collection of Georgia materials will continue to inspire and teach future generations. Though not born here, Ed Jackson was one of Georgia’s great treasures, and the people of this state that he served so long and so well are richer for all he taught us.”

When the Georgia flag-change controversy was at its height in the early part of this century, Ed was the go-to expert. He lectured on the history of our state’s flags for GHS in Athens and Savannah and published an article about it in the Georgia Historical Quarterly. And who else do you know that was awarded the “Vexillonnaire Award” by the North American Vexillological Association? Ed was, in 2004, for his work with the Georgia General Assembly’s efforts to redesign Georgia’s state flag. (Vexillogy is the study of flags, and no, I didn’t know that either.)

Ed had an extensive stamp collection (he was a founding member of the Georgia Federation of Stamp Clubs, now called the Southeast Federation of Stamp Clubs), and he once lectured here in our Research Center during the Georgia History Festival on Georgia history as told through stamps.

When the online New Georgia Encyclopedia needed an authority to write the entry for Georgia’s founder himself, James Edward Oglethorpe, they chose Ed. That forbidding subject would have daunted most historians, but not him. (That’s Ed in the center of the picture to the right, taking a photograph at Oglethorpe’s tomb in England.) For good measure, he also wrote seven other entries for the NGE, including for Georgia’s Historic Capitals, the Dixie Highway, Georgia’s State Flags, the current Georgia State Capitol, and the Legislative Process. He also served as a section editor for the NGE.

When the online New Georgia Encyclopedia needed an authority to write the entry for Georgia’s founder himself, James Edward Oglethorpe, they chose Ed. That forbidding subject would have daunted most historians, but not him. (That’s Ed in the center of the picture to the right, taking a photograph at Oglethorpe’s tomb in England.) For good measure, he also wrote seven other entries for the NGE, including for Georgia’s Historic Capitals, the Dixie Highway, Georgia’s State Flags, the current Georgia State Capitol, and the Legislative Process. He also served as a section editor for the NGE.

Every time I called Ed and needed help, he was always happy to assist, whether it was asking him to write an article for GHS’s Georgia History Today popular history magazine (where he wrote about the Dixie Highway, FDR in Georgia, and any number of his other passions), querying him about a fact on a proposed historical marker, or to answer one of my many arcane questions about Georgia history. He was never too busy, he never said no, and he never took a dime for all he did for GHS. If he could help further the mission of Georgia history, he would.

It’s no exaggeration to say that we would not have been able to do “Today in Georgia History” in conjunction with Georgia Public Broadcasting without Ed Jackson. It was his website, “GeorgiaInfo,” created for the Vinson Institute, that provided a roadmap for all the subjects we’d cover day to day over the course of the year. Naturally, he made it all available to us—and to everyone else—without any desire for personal credit. He only wanted to teach Georgia history, and if his website helped GHS and GPB do that, then he was glad to help.

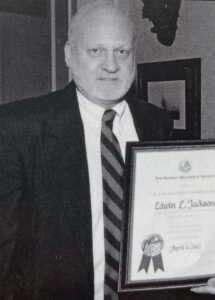

GHS honored Ed in 2002 with the John MacPherson Berrien Award for Lifetime Achievement in Georgia history (pictured here), and in 2012 with the Sarah Nichols Pinckney Volunteer Award.

GHS honored Ed in 2002 with the John MacPherson Berrien Award for Lifetime Achievement in Georgia history (pictured here), and in 2012 with the Sarah Nichols Pinckney Volunteer Award.

Ed donated his vast and extraordinary collection of materials related to Georgia history to the GHS just a couple of years ago. The Edwin Jackson Collection at the Georgia Historical Society is now being processed, and when completed and opened for research it will be a treasure trove of riches that will be mined for decades to come.

Thank you, Ed, for all your years of self-less service to others, in the finest tradition of Non Sibi, Sed Aliis, Not for Self, But for Others, harkening back to the original Georgia Trustees. Thank you for your years of friendship to the Georgia Historical Society, to the University of Georgia, to the State of Georgia and her people—including all those yet unborn. They too are in your debt. Thanks to you, the path forward will be brighter for all those who look to the past to help light the way.

Georgia never had a better friend than this adopted son, and he will be deeply missed. He is quite irreplaceable.

We salute you, and farewell.

In this episode Stan interviews Dr. Johann Neem, historian and author, whose research focuses on the history of American democracy. They discuss history in the public realm, why history has become so controversial in recent years, and where it’s all headed.

Off the Deaton Path would like to introduce our readers to some of the scholars researching in the Georgia Historical Society’s newly expanded and renovated Research Center. This week we’ll spotlight Dr. J.E. Morgan, an NEH-ARP Postdoctoral Fellow at the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture in Williamsburg, Virginia, and, beginning this fall, a Visiting Assistant Professor at Emory University.

Tell Us About Yourself: I’m originally from Georgia and completed a B.A. at Georgia State, an M.A. in English at the University of Missouri, and an M.A. and Ph.D. in history at Emory. This spring, I wrapped up a year of teaching at the University of Florida as a Visiting Assistant Professor, and I’m currently an NEH-ARP Postdoctoral Fellow at the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture in Williamsburg, Virginia. At Emory and UF, I’ve taught courses on U.S. history from the colonial period to Reconstruction; histories of race and gender history in the Atlantic World and Revolutionary era; and, last spring, an undergraduate research seminar on the archive of slavery. In the fall, I will return to Emory as a Visiting Assistant Professor and am looking forward to teaching a course on the era of the American Revolution and another on women’s history in the colonial era through 1800.

Tell Us About Your Current Project: Currently, I’m working on my manuscript, entitled American Concubines: Gender, Race, Law, and Power. This project examines the shaping of southern society and culture around a practice that has long been called “concubinage.” This term shows up in manuscripts and print materials from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in historiographical sources, and in many other sources on slavery in the Atlantic world. Because this term appears in so many contexts and can be ambiguous in terms of its usage, an important part of my project is investigating the definitions of “concubinage.” I also examine the development of concubinage as a practice stemming from and reinforcing the power imbalance that informed sexual relations between White men and enslaved women in British slave societies. Many sources reveal that enslaved women often contested this imbalance in various ways and that it was occasionally upset by their actions. Conversely, enslavers used instances of contestation to strengthen their power over enslaved people and impose more stringent measures to ensure that enslaved women and their children by White men would be excluded from protections granted to White women and their children.

What Are you Finding at GHS? I’ve been researching at GHS since beginning my doctoral work, and it has been great to return year after year to work in the archive. During this time, I have collected information from documents connecting the development of slavery in Georgia to slavery in earlier British colonies. These include legal and state documents relating to slavery in early Georgia and family papers that include personal letters, diaries, and financial records that trace the development of a system of slavery in Georgia that drew upon plantation slavery in Carolina and the British Caribbean. Also valuable in many of these collections are correspondence and other materials that reveal specific cultural attitudes of eighteenth-century British Caribbean colonies regarding race and gender that influenced the development of laws regarding slavery in early Georgia. Some of these collections include Georgia and South Carolina Court Declarations; judicial records of various Georgia counties just after the American Revolution; and individual and family papers such as the Stanford Brown Collection (GHS 2564); the Joseph Vallence Bevan Papers (GHS 0071); the Couper and Wylly family papers (GHS 1872), the Jones family papers (GHS 0440), and the Sheftall family collection (GHS 1414).

Together, these kinds of sources can show us how laws were being written and interpreted in ways that both reflected and shaped the culture of early Georgia. They reveal the development of a system of slavery that drew upon those of Jamaica, Barbados, and Carolina. They also complicate understandings of how enslaved women in particular navigated their precarious positions within such brutal systems where security and safety were as elusive as freedom itself.

I’m grateful to everyone at the Research Center during my time there and look forward to future research trips!

The Georgia Historical Society welcomed the inaugural class of Dooley Distinguished Research Fellows to the GHS Research Center in May. The Research Fellows Program, part of the larger Vincent J. Dooley Distinguished Fellows Program, honors Vince Dooley for his lifelong commitment to history and higher education.

The Research Fellows Program is designed to mentor the next generation of historians by giving younger scholars the opportunity to conduct research for a specific period of time in the vast collection of primary sources at the Georgia Historical Society Research Center. The research is expected to lead to a major piece of scholarly work, such as a dissertation, a book, an article in a refereed scholarly journal, a chapter in an edited collection, or an academic paper presented at a scholarly conference. Click here to learn more about the Dooley Fellows program.

For the next several weeks Off the Deaton Path would like to introduce our readers to the 2022 Dooley Research Fellows to learn about their work, their research at GHS, and the experience of being a Dooley Distinguished Fellow. This week we’ll focus on Dawn Wiley, a Ph.D. student at the University of Alabama.

Tell Us About Yourself: As the daughter of a United States Navy Master Chief, I was born in the Philippines and grew up moving around quite often until my family finally settled in Atlanta when I was in middle school. I’ve called it home ever since.

I received my B.A. in Political Science with a minor in History from Georgia State University in 2010. I initially thought I wanted to go to law school, but I decided to pursue my true passion for history after working a year in the legal field. From there, I went on to earn an M.A. in History from Georgia State University in 2015 while working and traveling full time as a litigation paralegal at a prestigious national law firm.

I knew I had only scratched the surface when I successfully defended my master’s thesis on southern women during the Civil War. After receiving the Georgia Historical Records Advisory Council Award for Excellence in Student Research for my thesis in 2016, it only confirmed that my project was worthy of further exploration and also had great potential to expand the field of women and gender in the United States South. I made the decision to enter the history program at The University of Alabama in 2017 because of all that it had to offer to graduate students.

Although my time at UA did not come without challenges or adversity, it has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. From receiving quality instruction from distinguished professors on how to teach at the college level and become a professor in the future, to fully funded research trips abroad, and the opportunity to act as editor of a graduate student-run academic journal called The Southern Historian, I am extremely fortunate for my training as a historian at UA and look forward to a career in academia. Under the direction and guidance of absolutely brilliant scholars that make up my dissertation committee, (Joshua Rothman, Kari Frederickson, Andrew Huebner, and Holly Grout), I am carefully undergoing the process of researching and writing my dissertation with hopes of defending in late 2023.

What Interested You in the Dooley Distinguished Fellowship? What has your experience been like here at GHS? I was particularly interested in applying for the Dooley Distinguished Fellowship because of the nature of my dissertation. Since my project is strictly a study of Georgia during the Civil War, and for the simple fact that Savannah is one of the three areas in the state I am examining, I knew that the GHS would hold primary sources most pertinent to my work. A quick search on the GHS website under the online catologue/finding aid yielded several results for journals, letters, ledger books, memoirs, and pension applications that I knew would support my arguments and therefore, became eager to explore them in person. I am very thankful that I was selected as one of the Fellows because the sources I found have not been used (to my knowledge) in the existing literature. I am excited at the prospect of bringing these sources to light in the dissertation, and if all goes well, the manuscript for my first book!

My experience at GHS was unmatched by any archive I have ever visited in my time as an M.A. and Ph.D. student. From the time I was first informed of receiving the award, to undergoing the uncertainty of the pandemic, and finally arriving in Savannah to complete the research, the team at GHS provided me with every resource and attention I needed and thoroughly answered any questions I had. I am most indebted to all of the archivists for their willingness to help me navigate finding aids, microfilm, and even suggest I look into sources that I had not yet considered or even knew existed. Most especially, I thank Nate Pederson and Stan Deaton, not only for facilitating the fellowship process but for their genuine efforts to ensure that my time at GSH was a complete success.

Finally, most graduate students would agree that the pandemic not only put a hold on their research plans but also on the important social aspect of conversing with other scholars. This fellowship at GHS afforded me one of the first opportunities I’ve had since getting back to the “new normal” to speak about my research with someone other than my advisors. Interactions with the other Fellows, Tracy Barnett and Lewis Eliot, were most fruitful because we were able to discuss new scholarship and bounce research ideas off each other. It was an added pleasure to share my dissertation project and findings at the archives with the entire GHS staff during an informal presentation in the Jepson House Education Center’s beautiful gardens. I’m looking forward to keeping in touch with everyone I’ve met during my time as a Dooley Distinguished Fellow, and hopefully, continue engaging in conversations that will inspire me to produce the best work possible.

Tell Us About Your Current Project: Scholars of the American Civil War have long contended that the war became an impetus for drastic change in many aspects of American life. Included in these changes were the role of women, traditional class hierarchies, and public welfare assistance in the Unites States South. In my dissertation, entitled “We the Soldiers’ Wives: Gender, Class, and the Welfare State in Civil War Georgia, 1860-1877,” I study changing nineteenth-century class structures, the transformation of gender roles and the family, White women’s involvement in politics and the public sphere, and finally, a rapidly expanding welfare state during the Civil War and Reconstruction era. More specifically, my project examines White non-elite Georgia women’s petitions and personal correspondence to government officials and male family members away at war, as well as their grassroots organized protests, to discover how these issues developed in Civil War and Reconstruction-era Georgia.

In recent Civil War studies, historians have placed increasing focus on Southern women, class, and welfare politics. Though scholars have deepened our understanding of these issues within the past two decades, several crucial gaps remain in the current literature that need further investigation, particularly in the state of Georgia. Divided into three chronological parts (Antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction), my dissertation first explores nineteenth-century gender roles and class structures for white women in the state of Georgia in the Antebellum era. I attempt to provide a full-length treatment of the complexity of southern class structures for White citizens in the state of Georgia, while contributing to a historiography normally dominated with studies of the planter elite by highlighting the lived experiences of an active urban middle class and yeoman class in the state of Georgia.

The Civil War portion of my dissertation examines the ways the war transformed both class hierarchies and traditional gender roles for women as heads of households and as political entities. I also investigate the changing relationship between White women and their male kinfolk and the Confederate government in the state of Georgia, as well as the earliest beginnings of a welfare state. Moreover, I explore the extent to which the actions of White non-elite women affected the Georgia government’s decision to create a specific Confederate welfare policy for soldiers’ wives, widows, and their dependents. This investigation allows me to test the argument some scholars have made that women’s “politics of subsistence and survival” during the war affected the state’s decision to create a specific Confederate welfare policy for soldiers’ wives, widows, and their dependents, and ultimately, crippled the Confederacy’s ability to wage war as a result.

The post-war years conclude my dissertation with an investigation of how White non-elite Georgia women engaged in the public and political sphere in the Reconstruction era. I also hope to include how Black soldiers and their families played active roles in the expansion of the welfare state after they won their independence in Reconstruction-era Georgia.

What Are you Finding at GHS? To say that I hit the primary source “jackpot” at the GHS would be an understatement!

I spent the first day of my fellowship examining letters between husbands away at war and wives on the homefront during the war. Letters such as the Francis L. Mobley Letters (MS 1822) and the Julian M. Burnett Civil War Correspondence (MS 0911) not only provide evidence that the war induced material and economic deprivation for Georgia women at home but also gives context into the relationship between spouses during the war. These letters are a strong indicator of how much influence women wielded on their husband’s decision to remain or flee the ranks when conditions at home became unbearable as the war progressed. I am finding that although these soldiers did request leaves of absences and furloughs from Confederate service, they remained in the ranks when those requests were denied, thus Georgia soldiers held a higher loyalty to the Confederacy than becoming more beholden to answer calls from the homefront.

When sparking up a conversation of my interest in looking at different classes of women and their activity in Civil War Savannah, GHS Reference Assistant Meaghan Gray pointed me in the direction of two sources that were not on my original “pull list” but quickly became a welcome surprise. The first was the Savannah City Directory for 1860. This directory listed men, as well as women, their occupations, addresses, and businesses in the year before the outbreak of the Civil War. Prominent historians have argued that Savannah contained virtually no middle class, but a quick look into this directory shows that civilians worked as “merchants, business owners, shop keepers, etc.” suggesting that a thriving urban middle class did in fact exist in Savannah. It confirmed my suspicion that historians and scholars of the South may need to think more carefully about how we construct class hierarchies. Perhaps the time is now to re-evaluate current interpretations of class in the existing literature and take into consideration what socio-economic structures look like in different parts of the state (rural vs. urban areas).

Secondly, Meghan informed me of the Chatham Artillery Records (MS 0966), one of the oldest military organizations in the state of Georgia. An investigation of these documents led me to discover the Savannah Ordnance Depot Employment Roll (GHS 0701), which later became the Savannah Arsenal in 1864. The “Roster of the Civilians Employed and Occupations” exposed that Savannah women sought wage work at the arsenal as clerks and cartridge makers. This is similar to my findings of women wage workers at the Atlanta Arsenal and adds to my overall argument that the Civil War upended the nature of traditional gender roles and women’s work for Georgia women. Furthermore, this lends further proof to my assertion that women advocated for themselves and their families by entering wage work as a subversive strategy of survival, while keeping their femininity intact.

Also of note are the Savannah Widows Society Records (MS 1651) and the Louisa Porter Foundation Records (MS 0500). These organizations were some of the earliest forms of public welfare assistance for destitute and poor women and children in the city of Savannah. These records cover the antebellum era, the Civil War years, and the Reconstruction era and will undoubtedly become a rich source to consult when examining Georgia women’s influence on Civil War and post-war public welfare policy in greater depth.

These are just a few highlights of my many discoveries at the GHS. I am excited to dive deeper into my analysis of these sources in the coming months of dissertating and hopefully, provide more awareness into what awaits prospective researchers and scholars at GHS. It was truly an honor being a Dooley Distinguished Fellow, and I thank the staff at GHS again for this fantastic opportunity!