On Monday, May 16, 1763, 261 years ago this week, young James Boswell was introduced to Samuel Johnson at Thomas Davies’s bookshop on Russell Street, near Covent Garden in London. Boswell was a 22-year-old Scotsman, perhaps best described as what we’d today call a “social influencer”—he wanted to be famous, and he was hugely ambitious. Johnson was 53, an already-acclaimed writer and author that Boswell desperately wanted to meet. Boswell famously described their meeting years later: Boswell went to his friend Davies’s bookstore for afternoon tea, and in walked Johnson. Introducing the two, and knowing the grumpy Johnson’s dislike of the Scots, Davies playfully revealed Boswell’s nationality. Boswell blurted out, ““Mr. Johnson, I do indeed come from Scotland, but I cannot help it.” Johnson’s riposte: “That, Sir, I find, is what a very great many of your countrymen cannot help.” Such was the beginning of one of the most famous—if bumpy—friendships in all of literature.

On Monday, May 16, 1763, 261 years ago this week, young James Boswell was introduced to Samuel Johnson at Thomas Davies’s bookshop on Russell Street, near Covent Garden in London. Boswell was a 22-year-old Scotsman, perhaps best described as what we’d today call a “social influencer”—he wanted to be famous, and he was hugely ambitious. Johnson was 53, an already-acclaimed writer and author that Boswell desperately wanted to meet. Boswell famously described their meeting years later: Boswell went to his friend Davies’s bookstore for afternoon tea, and in walked Johnson. Introducing the two, and knowing the grumpy Johnson’s dislike of the Scots, Davies playfully revealed Boswell’s nationality. Boswell blurted out, ““Mr. Johnson, I do indeed come from Scotland, but I cannot help it.” Johnson’s riposte: “That, Sir, I find, is what a very great many of your countrymen cannot help.” Such was the beginning of one of the most famous—if bumpy—friendships in all of literature.

I wrote about Boswell in another blog entry from December 10, 2014, nearly 10 years ago, and on this auspicious anniversary of that famous meeting, I can do no better than to quote a bit from that post (with slight editing) again here:

“I am lost without my Boswell.” So says Sherlock Holmes about Dr. Watson in “A Scandal in Bohemia.” Boswell is most famous as the author of the monumental biography, The Life of Samuel Johnson, first published in 1791 and never out of print. I bought a nice Easton Press edition in three volumes a few years back and loved it. Boswell is best known as Johnson’s biographer, but he was a fascinating and complex man in his own right, well worthy of our attention, and his published journals are just the place to start.

Boswell would be well at home in today’s world of social media. He kept extensive journals throughout his life, covering the most intimate details of his private goings-on and detailed transcriptions of his conversations with the great men and women of 18th-century Britain, including Georgia’s founder James Edward Oglethorpe, Samuel Johnson of course, the artist Joshua Reynolds, actor David Garrick, writer Oliver Goldsmith, the aforementioned David Hume, Voltaire, and many, many others.

And just like today’s most avaricious social media posters, he held nothing back, even when he probably should have. He wrote about everything: politics, art, literature, court intrigues, his sexual and sensual escapades (including cavorting with London’s prostitutes and contracting and living with an STD), the peccadilloes of his friends and associates, falling out with his father over his chosen career, his fear of ghosts, and everything else you can imagine. He was an inveterate sinner who feared damnation but would walk out of a church and have sex with a prostitute. Sometimes he would miss the sermon because he was lusting over a woman in another pew. It is about as revealing a snapshot of everyday life in 18th-century Britain—and a man driven by and forever at war with his passions—as we are ever likely to have, and it is all fascinating, a ripping good read.

Boswell died in 1795 at age 54, leaving behind a wealth of personal papers and journals that he hoped would one day be published. His family, however, had other ideas. Generations of his descendants thought his writings inappropriate and scandalous, detailing as they did his every whim, fancy, and indiscretion. They were also ashamed of their association with a man whom they considered to have lowered himself by acting the sycophant to the overbearing and boorish Johnson simply to obtain material for his biography.

Boswell’s descendants didn’t exactly lose his writings, but it’s safe to say they put them away and mostly forgot about them as they passed from generation to generation. They were “rediscovered” in the 1920s and 1930s in a croquet box at Malahide Castle in Ireland and in a stable loft at the home of a Scottish laird at Fettercairn House near Aberdeen.

The story of the Boswell Papers’ disappearance and re-discovery is told in fascinating if sometimes excruciating details in Frederick Pottle’s Pride and Negligence: The History of the Boswell Papers (1981) and in David Buchanan’s more enthralling The Treasures of Auchinleck: The Story of the Boswell Papers (1974). Pottle was a lifelong Boswell scholar and edited, in the “Boswell Factory” at Yale, all but one of the thirteen volumes of the popularly published journals that begin with the London Journal.

When Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763, was first published in 1950, it was a surprising best seller and one can see why. It’s racy and titillating, gossipy and erudite, introspective and philosophical, witty and just plain fun. There are two famous scenes in these pages: Bozzy’s first meeting with Johnson on May 19, 1763, of course, but also the memorable day when he confronts his girlfriend Louisa as to whether she knowingly gave him a venereal disease: “Madam, I have had no connection with any woman but you these two months. I was with my surgeon this morning, who declared I had got a strong infection, and that she from whom I had it could not be ignorant of it. Madam, such a thing in this case is worse than from a woman of the town, as from her you may expect it. You have used me very ill. I did not deserve it.” Louisa protested her innocence, but to no avail. Boswell stormed out and ended the relationship. Later in a quieter moment he confessed to his journal that he’d had this same disease twice before, but if he ever apologized to poor Louisa, the journal is silent.

Boswell kept on writing till his last days, and though his father scolded him for keeping “a register of his follies and communicat[ing] it to others as if proud of them,” we are the ultimate beneficiaries. There are twelve other volumes after this one and I look forward to reading them all.

***

With the publication of Boswell’s Journals, the perception of the famous friendship has begun to change: Boswell has come into his own as one of the great historical figures of the 18th century, a flawed genius that, for many people, now eclipses Johnson’s brilliance. In Clifton Fadiman’s words, “the disciple is beginning to overshadow the master.” Boswell, he rightly insisted, “is more than a superb reporter. He is an artist, just as surely as Rembrandt.”

The literature on Boswell, Johnson, and their famous friendship is vast, but start, as mentioned above, with the London Journal, then read as many of the other Journals as you desire. I’ve since read six volumes now, with seven more to go. They never disappoint. And of course, read Boswell’s Life of Johnson, which critic Michael Dirda called “the greatest of all biographies and probably the most entertaining book in English literature.”

But you don’t have to stop there. In addition to the Pottle and Buchanan books cited above, I recommend the following: Frederick Pottle, James Boswell: The Earlier Years, 1740-1769 (1966); W. Jackson Bate, Samuel Johnson (1977, winner of the 1978 Pulitzer Prize for Biography); Frank Brady, James Boswell: The Later Years, 1769-1795 (1984); Peter Martin, A Life of James Boswell (2000); Liza Picard, Dr. Johnson’s London (2001); Adam Sisman, Boswell’s Presumptuous Task: The Making of the Life of Dr. Johnson (2001) Peter Martin, Samuel Johnson: A Biography (2008); John B. Radner, Johnson and Boswell: A Biography of Friendship (2013); and Leo Damrosch, The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped An Age (2020).

But you don’t have to stop there. In addition to the Pottle and Buchanan books cited above, I recommend the following: Frederick Pottle, James Boswell: The Earlier Years, 1740-1769 (1966); W. Jackson Bate, Samuel Johnson (1977, winner of the 1978 Pulitzer Prize for Biography); Frank Brady, James Boswell: The Later Years, 1769-1795 (1984); Peter Martin, A Life of James Boswell (2000); Liza Picard, Dr. Johnson’s London (2001); Adam Sisman, Boswell’s Presumptuous Task: The Making of the Life of Dr. Johnson (2001) Peter Martin, Samuel Johnson: A Biography (2008); John B. Radner, Johnson and Boswell: A Biography of Friendship (2013); and Leo Damrosch, The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped An Age (2020).

As for the date of that famous meeting, Boswell missed dying on the anniversary itself by three days—32 years later—on May 19, 1795. He is buried in the family vault at Auchinleck Old Churchyard in Auchinleck, Scotland. Johnson died on December 13, 1784, at age 75, and is buried in Westminster Abbey.

But how’s this for coincidence? Frederick Pottle, the man who spent nearly his entire professional career as the editor and biographer of Boswell and his papers, considered the greatest Boswell scholar of all, himself died on the anniversary of that famous meeting, on May 16, 1987, at age 89. I suspect that would have pleased Dr. Pottle very much. No Westminster Abbey for him: Pottle is buried, appropriately, at Elmwood Cemetery in quiet Otisfield, Maine.

Alas, the Boswell Papers Project at Yale that Pottle captained for so long is no more, unceremoniously shut down by Yale bean counters during the pandemic. But the great friendship that began on that long-ago Monday in a London bookstore lives on for all of us to discover and explore, not only through print but now also on numerous social media pages and forums, dedicated to every aspect of Boswell, his life, and his world, in all his wickedness and glory—which he most assuredly would have loved.

Savannah, May 16, 2024

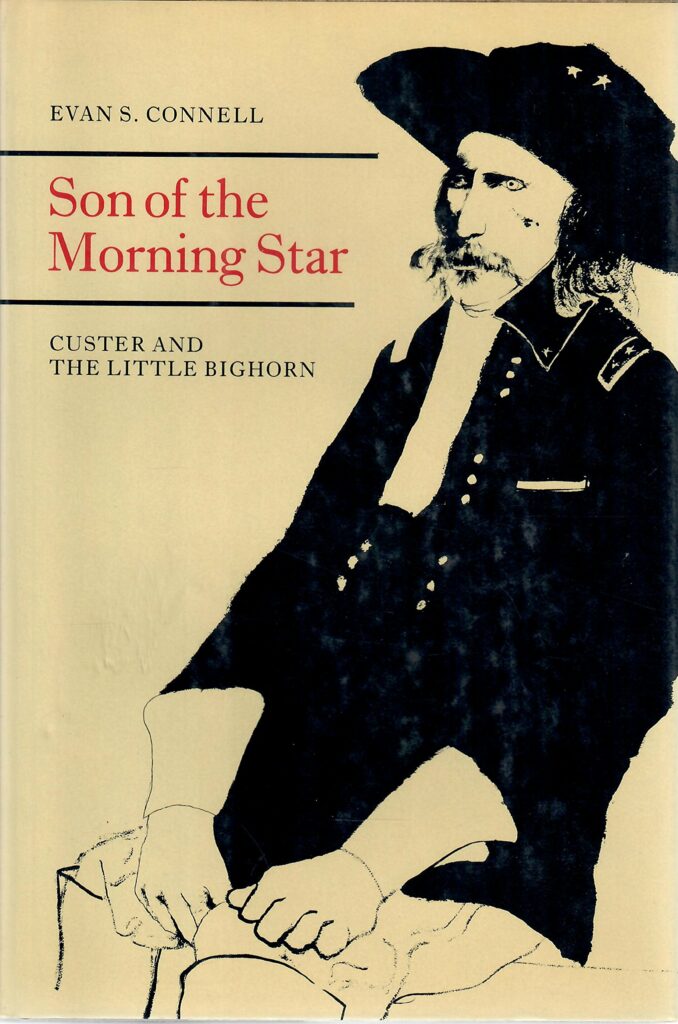

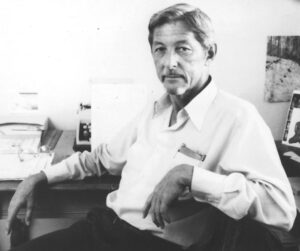

Item: Books, or A Case of Serendipity: I recently bought a copy of T.J. Stiles’s 2015 book, Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America, which won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for History. As I was putting it on the appropriate shelf in my office, I noticed immediately beside it my copy of Evan Connell’s 1984 best-seller on Custer, Son of the Morning Star, which has been hailed as a masterpiece. I remember buying the book as an undergraduate at UGA just getting interested in history. Why had I never read it? And who was Evan Connell? I remember reading articles in the mainstream media (like Time magazine) about how this unusual book and author surprisingly took the literary world by storm that year. I did the usual Google searches on Connell and found myself fascinated by what I discovered. Suffice it to say, Connell is considered a writer’s writer, at home in nearly every genre, from fiction, essays, and short stories, to history, biography, and poetry. The contemporary of Jack Kerouac, Philip Roth, and John Updike labored in comparatively undeserved obscurity, but hiding in plain sight was part of his deliberate brand. Connell, who died in 2013 at age 88, was a lifelong unmarried loner, the opposite of a self-promoter, who hated publicity and never courted the spotlight. He granted few interviews (none on camera) and if there’s a picture out there anywhere of him smiling, I’ve never seen it. He never did public readings of his work, never spoke publicly about his writing, never taught classes about writing or literature. He lived in the Bay Area much of adult life, spent some time in local watering holes, and formed few permanent attachments. He

Item: Books, or A Case of Serendipity: I recently bought a copy of T.J. Stiles’s 2015 book, Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America, which won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for History. As I was putting it on the appropriate shelf in my office, I noticed immediately beside it my copy of Evan Connell’s 1984 best-seller on Custer, Son of the Morning Star, which has been hailed as a masterpiece. I remember buying the book as an undergraduate at UGA just getting interested in history. Why had I never read it? And who was Evan Connell? I remember reading articles in the mainstream media (like Time magazine) about how this unusual book and author surprisingly took the literary world by storm that year. I did the usual Google searches on Connell and found myself fascinated by what I discovered. Suffice it to say, Connell is considered a writer’s writer, at home in nearly every genre, from fiction, essays, and short stories, to history, biography, and poetry. The contemporary of Jack Kerouac, Philip Roth, and John Updike labored in comparatively undeserved obscurity, but hiding in plain sight was part of his deliberate brand. Connell, who died in 2013 at age 88, was a lifelong unmarried loner, the opposite of a self-promoter, who hated publicity and never courted the spotlight. He granted few interviews (none on camera) and if there’s a picture out there anywhere of him smiling, I’ve never seen it. He never did public readings of his work, never spoke publicly about his writing, never taught classes about writing or literature. He lived in the Bay Area much of adult life, spent some time in local watering holes, and formed few permanent attachments. He  died alone in Santa Fe, New Mexico. And yet his novels reveal a remarkably penetrating insight into human relationships that are astonishing for someone who seemed to spend most of his life shunning them. His 1959 novel Mrs. Bridge (a National Book Award finalist) was praised as a masterpiece of spare, lean, concise story-telling, with not a spare word in it, as was his 1969 follow-up, Mr. Bridge. I bought and devoured them both and wished for more. I finally also read Son of the Morning Star (published by then-little-known North Point Press in Berkeley, now owned by FSG) and found it beautifully written and moving as well. The New York Times called it “impressive in its massive presentation of information” and added that “its prose is elegant, its tone the voice of dry wit, its meandering narrative skillfully crafted.” The Washington Post said it “leaves the reader astonished,” and the Wall Street Journal called it “a scintillating book, thoroughly researched and brilliantly constructed.” I can confirm that all of this is true. Happily, for people like me who are fascinated by him, there’s a new literary biography of Connell out by Steve Paul, Literary Alchemist: The Writing Life of Evan S. Connell, published in 2021 by the University of Missouri Press. And so, through the serendipity of shelving one book, Evan Connell is now on my list as a favored author whose writings I plan to work through patiently and in their entirety, one bite at a time. I’ll be spending considerable time with him in the coming years. If you love the power of words, I invite you also to get to know this talented, mysterious man in the only way we can—through his writing.

died alone in Santa Fe, New Mexico. And yet his novels reveal a remarkably penetrating insight into human relationships that are astonishing for someone who seemed to spend most of his life shunning them. His 1959 novel Mrs. Bridge (a National Book Award finalist) was praised as a masterpiece of spare, lean, concise story-telling, with not a spare word in it, as was his 1969 follow-up, Mr. Bridge. I bought and devoured them both and wished for more. I finally also read Son of the Morning Star (published by then-little-known North Point Press in Berkeley, now owned by FSG) and found it beautifully written and moving as well. The New York Times called it “impressive in its massive presentation of information” and added that “its prose is elegant, its tone the voice of dry wit, its meandering narrative skillfully crafted.” The Washington Post said it “leaves the reader astonished,” and the Wall Street Journal called it “a scintillating book, thoroughly researched and brilliantly constructed.” I can confirm that all of this is true. Happily, for people like me who are fascinated by him, there’s a new literary biography of Connell out by Steve Paul, Literary Alchemist: The Writing Life of Evan S. Connell, published in 2021 by the University of Missouri Press. And so, through the serendipity of shelving one book, Evan Connell is now on my list as a favored author whose writings I plan to work through patiently and in their entirety, one bite at a time. I’ll be spending considerable time with him in the coming years. If you love the power of words, I invite you also to get to know this talented, mysterious man in the only way we can—through his writing.

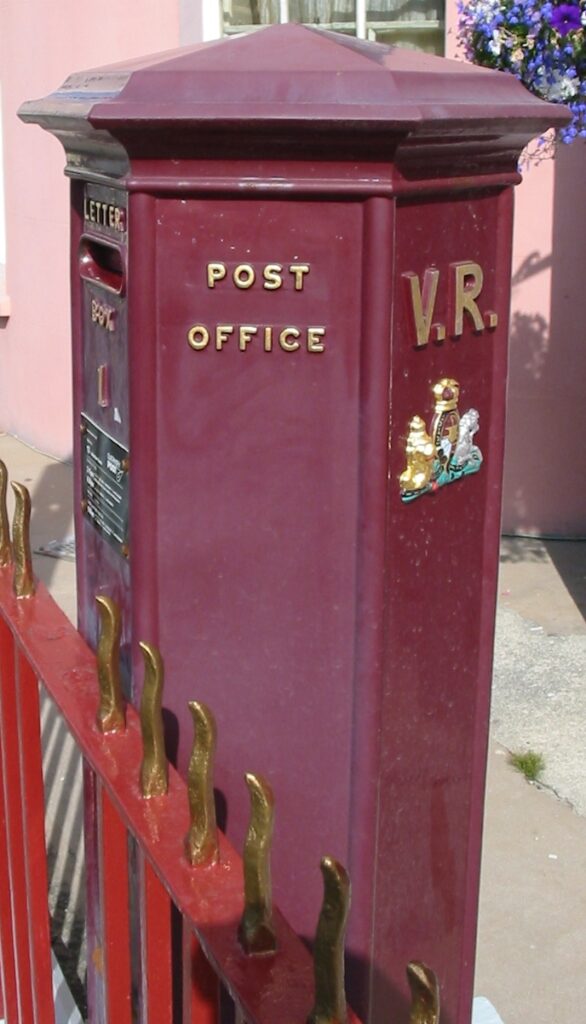

Item: Currently Reading: The Last Chronicle of Barset, by Anthony Trollope (originally published in 1867), the final volume (of 6) in the Barsetshire series that begins with The Warden (1855) then continues with Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), and The Small House at Allington (1864), chronicling the always interesting goings-on in the fictional county of Barsetshire and its cathedral town of Barchester during the height of the Victorian Era. The county is peopled with delightful almost-living characters like The Rev. Mr. Quiverful, Mrs. Proudie, Sir Omicron Pie, Dr. Fillgrave, Sir Abraham Haphazard, Sir Raffle Buffle, and many, many others. The series is beloved by Trollope fans, who are legion, ranging from actor Alex Guinness (Obi-Wan Kenobi), who never travelled without a Trollope novel, to economist John Kenneth Galbraith, to author Sue Grafton. It’s taken me 14 years to read the series, not because the books are hard to read—just the opposite; one critic said they’re like eating peanuts, hard to stop—but because I let too many years elapse between volumes. After this, it’s on to Trollope’s 6-volume Palliser series, which I hope to finish in half the time. Maybe I’ll read those straight through? At any rate, Trollope is also one of my favorite authors, not only for his wonderful books but because of how he wrote them. He famously kept to a disciplined schedule, putting in 3 hours at his writing desk every day before going to his real job at the Post Office, where he is credited with introducing the ubiquitous red pillar mailbox to the United Kingdom (seen here). His literary output was prodigious by any standards: 47 novels, 42 short stories, 5 travel books, 2 works of non-fiction, and an auto-biography. I intend to read them all.

Item: Currently Reading: The Last Chronicle of Barset, by Anthony Trollope (originally published in 1867), the final volume (of 6) in the Barsetshire series that begins with The Warden (1855) then continues with Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), and The Small House at Allington (1864), chronicling the always interesting goings-on in the fictional county of Barsetshire and its cathedral town of Barchester during the height of the Victorian Era. The county is peopled with delightful almost-living characters like The Rev. Mr. Quiverful, Mrs. Proudie, Sir Omicron Pie, Dr. Fillgrave, Sir Abraham Haphazard, Sir Raffle Buffle, and many, many others. The series is beloved by Trollope fans, who are legion, ranging from actor Alex Guinness (Obi-Wan Kenobi), who never travelled without a Trollope novel, to economist John Kenneth Galbraith, to author Sue Grafton. It’s taken me 14 years to read the series, not because the books are hard to read—just the opposite; one critic said they’re like eating peanuts, hard to stop—but because I let too many years elapse between volumes. After this, it’s on to Trollope’s 6-volume Palliser series, which I hope to finish in half the time. Maybe I’ll read those straight through? At any rate, Trollope is also one of my favorite authors, not only for his wonderful books but because of how he wrote them. He famously kept to a disciplined schedule, putting in 3 hours at his writing desk every day before going to his real job at the Post Office, where he is credited with introducing the ubiquitous red pillar mailbox to the United Kingdom (seen here). His literary output was prodigious by any standards: 47 novels, 42 short stories, 5 travel books, 2 works of non-fiction, and an auto-biography. I intend to read them all. Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Downfall, 1939-1945 (Alfred A. Knopf, 2020, 838 pp.).

Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Downfall, 1939-1945 (Alfred A. Knopf, 2020, 838 pp.).