April 15 marks the anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. Dr. Deaton discusses a forgotten Georgia writer onboard that night: Jacques Futrelle.

Category Archives: Writers

The Greatest Novel Ever Written?

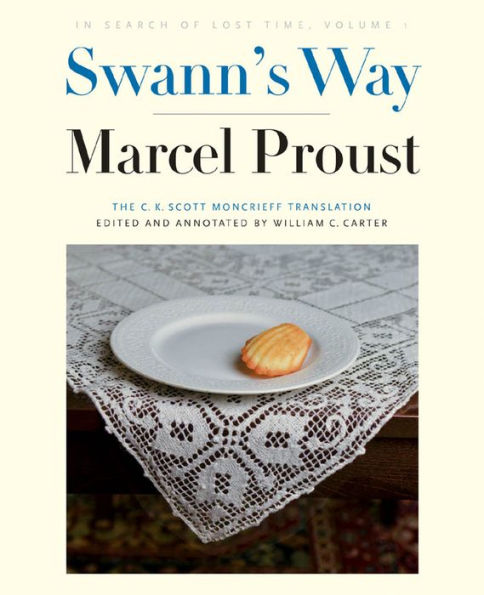

Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way: In Search of Lost Time, Volume 1. The C. Scott Moncrieff Translation, Edited and Annotated by William C. Carter (1913; rpt. Yale University Press, 2013, 487 pp.)

“What are you reading these days, Stan?”

“Proust.”

Let’s face it, one of the best reasons for reading an author like Marcel Proust is being able to tell people that you’re reading an author like Marcel Proust. To get the full effect, you should be wearing a bow tie, adjusting your monocle, and holding a pipe.

While I was reading Proust, I had no less than three occasions to tell inquiring minds that I was reading Proust, just as if I’d tee’d it up myself. Even without the bow tie, monocle, or pipe the effect remained the same: the questioner seemed impressed, slightly bemused, or downright baffled by my choice of summer reading. Responses ranged from “Hmm, something heavy,” to “A little light reading, huh?” to “Who?”

My own response might be, “Why?”

The reason, of course, is that Proust is one of those writers, like James Joyce, William Faulkner, and Thomas Wolfe, that usually show up on the list of 20th-century authors who are “must-reads.” But are they really? You began to wonder once you start reading their books. Their writing can seem like trying to climb the literary Mount Everest–forbidding, daunting, and, yes, even unreadable. Who hasn’t cracked open Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury and wondered, what the hell is even going on here?

In Search of Lost Time is made up of not one but seven volumes, of which Swann’s Way is the first. Proust published it at his own expense in 1913; he published two more volumes before his death in 1922 and the last four were published posthumously between 1923 and 1927.

“This is the longest first-rate novel ever written. Its difficulties, like its rewards, are vast. If you respond to it at all (many do not) you may feel quite justified in spending what time you can spare over the next five or ten years making it a part of your interior world.” So wrote Clifton Fadiman in his essay on Proust in The Lifetime Reading Plan nearly 60 years ago. The Encyclopedia Britannica calls it “one of the most profound achievements of the human imagination.” All of this is still true.

What is this book about? In 1909 Proust experienced a moment that perhaps you’ve shared: the involuntary recall of a childhood memory. It happened through the act of eating a piece of bread dipped in tea. Struck by the impact of it, he committed the rest of his life to writing a novel about recapturing lost time, the vanished past that gives our lives beauty and meaning. The novel was formerly referred to as Remembrance of Things Past.

Sometimes it’s heavy sledding, and sometimes not. The prose is famously beautiful, but, as Fadiman says, Proust can analyze “with intolerable exhaustiveness” and you may agree with him and other critics that the book is “less like a narrative than a symphony.” Proust could challenge Henry James for sentences that go on for days, but for all the underbrush, when you do come upon a clearance the views are indeed magnificent.

To say that there is a Proust cult would be an understatement. Shelby Foote–he of Civil War and Ken Burns fame–read all seven volumes at least nine times in his life and considered him second only to Shakespeare among writers. Alan Jacobs in The Pleasure of Reading in the Age of Distraction (Oxford, 2011) wrote that one of his high school teachers affirmed that she read the entire seven volumes every summer “because the book was so great, and so deep, and so subtle that she always found something new in it, always had more to learn about it and through it.” Yale University Press is in the midst of publishing new editions of the C. Scott Moncrieff translation, edited and annotated by the renowned Proust scholar and biographer William C. Carter.

There seem to be three schools of thought on this tome: that it’s the greatest novel in the world; that it’s unreadable; or, finally, that it’s mammoth but minor. To which of these do I subscribe after finishing the first volume?

I did not find it unreadable, though I can definitely say that at times I felt like the proverbial buyer who wanders in but is “just looking around”–I wasn’t always sure what was going on but I admired everything and just kept moving. At this point I wouldn’t call it the greatest novel ever written, but give me another year and I’ll be ready to tackle the next volume.

If Proust really is better than Dickens, Tolstoy, Austen, Hugo, Dumas, or a host of others, he will be a mountain well worth climbing.

Check back with me in about ten years.

What I’m Reading Now: May 15, 2019

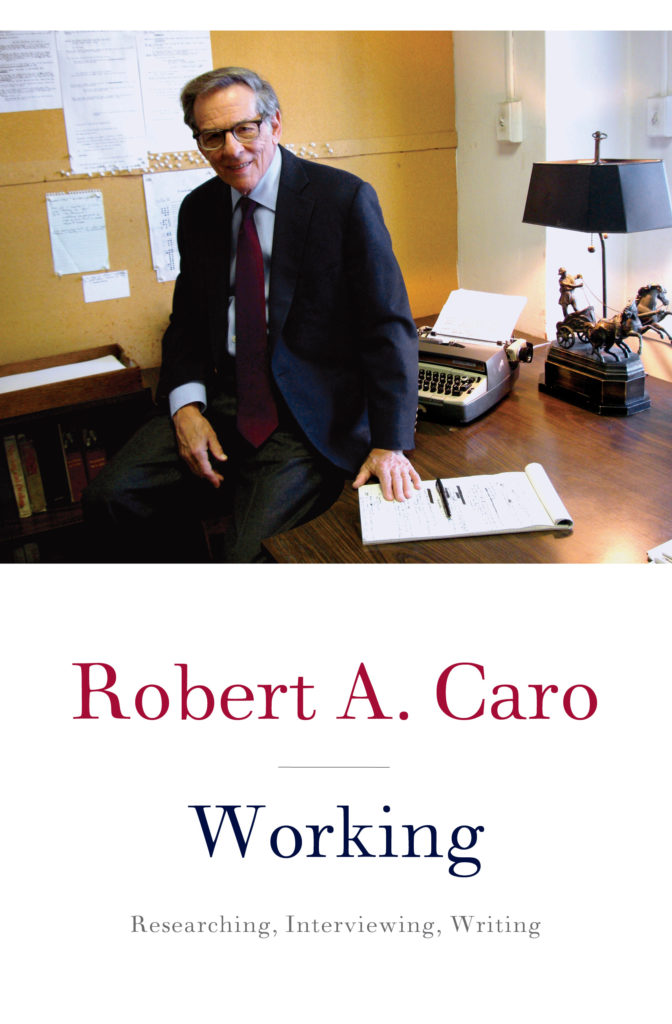

Robert A. Caro, Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing (Alfred A. Knopf, 2019, 207 pp.)

I’m fascinated by process. I’m never content to simply talk to someone about what they do, I always want to know how they go about doing it. This is especially true of writers and readers, even down to what the space looks like where they work.

There are a plethora of books written by writers about writing–including the one I wrote about in this blog, Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird. Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is one of the most popular and one of the best, in part because he gets down in the weeds about how to actually write, giving advice about everything from how to craft dialogue to how to find an agent.

More unusual is a writer who tells you how they actually work–what time of day they write, how many hours a day, how much time they spend researching, even the kind of paper, pen, or computer they use. I’m fascinated by all of it.

I well remember the afternoon in the fall of 1986, when, as a first-year graduate student at the University of Georgia, I was prowling the history stacks on the 4th floor of the Main Library and came across the sixth volume of Douglas Southall Freeman’s George Washington: A Biography.

Freeman died while the volume was in production, and Jefferson biographer Dumas Malone paid elegant tribute to Freeman in the Preface, entitled “The Pen of Douglas Southall Freeman.”

Here I first learned about Freeman’s Spartan schedule–rising at 2:30 in the morning, slavishly following the same routine every day, writing in the third-floor study of his home “Westbourne,” and tracking in a notebook every hour he spent working.

Mesmerized, I searched for every newspaper and magazine article I could find in those pre-Google days about this strange man who, by his own reckoning, spent 15,693 hours working on his biography of Washington. (Needless to say, I devoured David Johnson’s biography Douglas Southall Freeman when it was published in 2002.)

Robert Caro is in the midst of writing–as he puts it–the fifth of a projected four-volume biography of The Years of Lyndon Johnson, and he has paused in that task to produce this little gem about why he wrote and how he researched his lives of Robert Moses and LBJ. As fascinating as this book is, I have to wonder why at age 83 and needing about a dozen years to write each of the Johnson volumes, Caro decided to steal precious hours away from that book to write this one. And yes, he knows the clock is ticking.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s well worth it: Caro gives us a behind-the-scenes peek at his process, beginning with the advice proffered by his editor at Newsday, Alan Hathaway. He advised the young Caro that in his investigative reporting he should “turn every page. Never assume anything. Turn every goddamned page.”

Caro followed that advice through his massive study of New York commissioner Robert Moses and his four-volumes on LBJ–though he admits there aren’t enough lifetimes to turn every page in the LBJ Presidential Library, totaling 40,000 archival boxes and thirty-two million pages.

Caro is interested in power–where it comes from, how it works, and what people do with it. The famous mantra is that power corrupts but Caro insists that “power reveals.”

Robert Moses, the powerful NYC commissioner who, over the course of 40 years, built 627 miles of highways through New York’s five boroughs that uprooted hundreds of thousands of people (mostly the poor and minorities), had more power than any elected official, more power than the governor or the mayor, and he was never elected to anything.

How did he amass that kind of power? Caro was determined to find out, and he explains how he surmounted roadblocks placed by Moses himself, stonewalling by other Moses cronies, and the near-poverty he and his wife Ina endured as the book advance ran out and the research and writing stretched out into years. The story of what became the Pulitzer-Prize winning book The Power Broker (1973) is a tale of perseverance, dogged determination, and plain hard work. President Obama called it the most influential book he’s ever read.

To research LBJ, Caro and Ina moved to Austin, Texas (“why can’t you do a biography of Napoleon?” she pleaded). When they weren’t both trying to “turn every page” in the archive, he spent hundreds of hours driving hundreds of miles, interviewing LBJ connections in far-flung places to give his readers not just a sense of LBJ, but a far deeper understanding than anyone ever had of this paranoid, insecure, nakedly ambitious Texas Hill Country native and his relentless quest for power.

After reading Working, you’ll want to dive in to The Power Broker and not come out till you’ve finished the most recent LBJ offering, which I reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Have your calls held and your food sent in.

To return where we began: what is Caro’s process? After the research is done, and the writing begins, he wakes every morning at 7 a.m., puts on a coat and tie, and walks across Central Park to a small office he rents (he lost the one he had for 22 years on Columbus Circle to a Nordstrom). Sitting at an unadorned desk, with a vast outline tacked to a cork board on the wall, he writes three or four drafts in long-hand on narrow-lined white legal pads. He types up the next draft on a Smith-Corona Electra 210, triple-spaced, leaving plenty of room to re-write in pencil. Work stops in mid to late afternoon because he found that most of what he wrote in the evening didn’t pass inspection later. The next day he comes in, reads what he wrote the previous day, edits, and begins the process all over again.

Does he know the title of this last volume? He does. Will he tell us? He won’t.

The aforementioned Dumas Malone spent 33 years on his 6-volume Jefferson bio, not counting the years of research before the first volume appeared in 1947. He was 56 when that first volume was published, 89 and nearly blind at the last, and he died at 94.

We can only hope that Robert Caro has that many years left because we need him to finish this monumental task, and, who knows, maybe there will be enough years to spare to write the full-length memoir that he promises in these pages. Caro says that he will finish the 5th and final volume of LBJ in about 3-4 years, which would put him at 87.

As much fun and informative as this slim volume is, speaking on behalf of his legion of fans (including Conan O’Brien), we can only hope that Robert Caro doesn’t take on any more side projects that will delay, even for a day, the last LBJ volume.

The finish line is near, and the clock is ticking. Write, Mr. Caro, write.

S2E10: Steve Oney

Stan’s guest this week is prize-winning author and journalist Steve Oney, talking about his latest book, A Man’s World: A Gallery of Fighters, Creators, Actors, and Desperadoes (UGA Press) and his interviews with Greg Allman, Harrison Ford, Nick Nolte, Herschel Walker, and many others.

S2E8: A Charles Dickens Christmas: Christmas at Dingley Dell, from The Pickwick Papers

A special Christmas podcast, with Stan reading from one of his favorite books, as Mr. Pickwick and his fellow Pickwickians visit Dingley Dell Manor Farm for a good old fashioned English Christmas. Enjoy and Merry Christmas!