Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Downfall, 1939-1945 (Alfred A. Knopf, 2020, 838 pp.).

Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Downfall, 1939-1945 (Alfred A. Knopf, 2020, 838 pp.).

The first podcast that I ever recorded in this space, back in August 2017, reviewed the first volume of this fascinating biography of the Nazi Führer, Ascent: 1889-1939. Volume 2 followed here in the States in 2020, and I’ve just completed it. These 2 volumes are a worthy successor to the monumental biographies of Hitler by Ian Kershaw (2 volumes, 1998 & 2000), John Toland (2 volumes, 1976), Joachim Fest (1973), and Alan Bullock (1962).

Ullrich, the author, is German, born there in 1943 during the war, and it’s this nativity that gives his unsparing criticism of Hitler and his followers a moral weight it might otherwise lack. There is no trimming, no faint praise of the Nazis for making the trains run on time, no points for restoring German national morale after the devastation of the Great War—there is nothing here but unflinching critical analysis of the most heinous crimes ever carried out under the authority of government, all while focusing like a laser on the man from whose brain it all sprung.

This blog is not a full-on review of this book, simply a whole-hearted endorsement of it for anyone who wants to understand how the most evil regime in history came to power, held onto it for 12 years while demonizing Jews and other minorities, waged brutal and genocidal war, and then was utterly destroyed by the combined Allied might of the world’s leading democratic and communist regimes.

It is of course a story of unimaginable horror, but Ullrich’s real gift is helping us to see Hitler and his fellow Nazis as people, not as monsters.

This is important because, as he points out in the first volume, if they were in fact monsters then everything they did would be explainable. The fact is, they were flesh-and-blood human beings, which demands of good historians that they explain how the Nazis came to power with all their sociopathic and full-throated hatred for Jews, Eastern Europeans, and communists in full view. There were no secrets about what they intended to do. They then led one of the most cultured societies in Europe—not against its will, according to Ullrich—down the path of total war and ethnic annihilation, at the cost of hundreds of millions of lives.

To do all this is no easy task, but Ullrich pulls it off. Even as we already know the outcome, it is still a riveting story. Across 600+ pages of text we witness the invasion of Poland and the beginning of World War II, the air war with Britain, the fall of Paris, the titanic struggle with the Soviet Union, the enslavement and butchery of millions on the Eastern front, the Allied landing and the liberation of Europe, and the ongoing and horrific Final Solution. Through it all, Ullrich “normalizes” Hitler and in the process makes him seem more inhuman than ever, Still, as he writes, “there will always be aspects of Hitler we cannot explain.”

No matter how many books, documentaries, and films are produced about them, the story of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialists will remain a repelling and fascinating part of our history of which we can’t get enough. It is a subject that is both timely and bottomless. As Ullrich wrote in Volume 1, there will never be a “definitive” biography of Hitler because “people will never stop pondering this mysterious, calamitous figure. Every generation must come to terms with Hitler.”

As another German historian, Eberhard Jäckel wrote, “We Germans were liberated from Hitler, but we’ll never shake him off. Hitler will always be with us, with those who survived, those who came afterwards and even those yet to be born. He is present—not as a living figure, but as an eternal cautionary monument to what human beings are capable of.”

Adolf Hitler and the Nazis came to power 90 years ago this week, on January 30, 1933. The world is still coming to grips with the horrors of the Third Reich, even as anti-Semitism and authoritarianism are both again on the rise.

It is a stark warning to all of us that, though Hitler and his regime may be gone, their legacy and influence are not. Right now, there are those seeking power by demonizing other people and feeding the worst instincts to hate and fear other human beings. Hitler reminds us, as Ullrich concludes, “how thin the mantle separating civilization and barbarism actually is.”

We stand by and say nothing at our peril.

We received word here at GHS this week of the death of our dear friend Ed Jackson on Tuesday, January 10, 2023, age 79.

We received word here at GHS this week of the death of our dear friend Ed Jackson on Tuesday, January 10, 2023, age 79. When the online New Georgia Encyclopedia needed an authority to write the

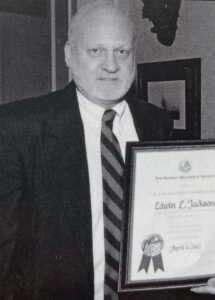

When the online New Georgia Encyclopedia needed an authority to write the  GHS honored Ed in 2002 with the John MacPherson Berrien Award for Lifetime Achievement in Georgia history (pictured here), and in 2012 with the Sarah Nichols Pinckney Volunteer Award.

GHS honored Ed in 2002 with the John MacPherson Berrien Award for Lifetime Achievement in Georgia history (pictured here), and in 2012 with the Sarah Nichols Pinckney Volunteer Award. How is this even possible? After all the angst, crushed dreams, and vanished hopes of the years spanning Ray Goff (1989-1995), Jim Donnan (1996-2000), and Mark Richt (2001-2015)—particularly the latter—how in the name of the Chapel Bell, Varsity chili dogs, and fried pies is this even possible?

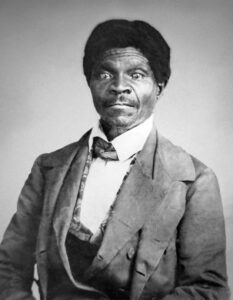

How is this even possible? After all the angst, crushed dreams, and vanished hopes of the years spanning Ray Goff (1989-1995), Jim Donnan (1996-2000), and Mark Richt (2001-2015)—particularly the latter—how in the name of the Chapel Bell, Varsity chili dogs, and fried pies is this even possible? The Supreme Court’s decision was highly anticipated—and was leaked before the Court’s announcement. The Court would be ruling on the most contentious issue of the age, one that had threatened to tear the country apart for decades. When it was announced, one side hailed it as the final word on a divisive subject, finally laying the issue to rest. The other side exploded in moral outrage, charging the court with action far beyond its jurisdiction by trying to solve a complex and difficult political issue, overturning a long-standing precedent, and vowed to disregard the ruling and take the appeal directly to the American people.

The Supreme Court’s decision was highly anticipated—and was leaked before the Court’s announcement. The Court would be ruling on the most contentious issue of the age, one that had threatened to tear the country apart for decades. When it was announced, one side hailed it as the final word on a divisive subject, finally laying the issue to rest. The other side exploded in moral outrage, charging the court with action far beyond its jurisdiction by trying to solve a complex and difficult political issue, overturning a long-standing precedent, and vowed to disregard the ruling and take the appeal directly to the American people.